RESPECTABILITY

By GEORGE E. BOWEN.

I saw society itself create,

Then prop with mocking laws its flimsy state.

Saw custom out of idle habit spring

And o'er the mob its rule of iron swing.

Saw vanities arise—small vapors, first;

That choked life's withering heart with fumes accursed.

Saw lust and greed their common creed enthrone

Above the fanes love's Arcady had known.

Saw wars and pestilence with hate despoil

The precious fruitage of all human toil.

Saw manhood bought and sold within the mart

Of soulless commerce—but the cheapest part.

Yet more I saw in the red lists of greed

To feed the clamor of imperial need:

Brown brothers of the wild to slaughter fed,

That peace might follow where the cannon led.

Brown brothers—shackled, body, mind and soul,

That Christian commerce win its sacred goal.

Brown brothers—noble in their native might,

Made servile to their saving ones of white.

This much society at last attained—

That man's redemption from the brute be gained.

Thus, in the name of commerce came a race

With sword and bible its sure means of grace,

To civilize the earth,. ounce round again,

Where primal systems fixed their laws in vain.

And who most scattered waste and want abroad

Found favor with the mass, himself and God.

But these immaculate, accepted hosts,

Invincible by oft repeated boasts,

Saved for their proudly undisputed fame

The sting and sorrow of a woman's shame.

I saw great masters of the land and sea—

Princes of men, as mighty moderns be,

Seal fast the law that gave their passion rein,

But held their weak companion's tears in vain.

Saw women of their favor—(duly wed)—

Sneer at their consorts of some brothel bed,

Then clutch the lying faith a priest had taught

To brace the pact by lust and lucre wrought.

Saw my astonished eyes, by fashion's sign,

Its creatures curse the miracle divine,—

Denounce with fury, for the social good,

The unrecorded joy of motherhood.

Saw, wantonly, these sisters (safely bought)

Cast out the one no licensed swain had sought,

While, by the cross whose open arms they wore,

Anathema upon her soul they swore.

Thus have men grown out of primeval spawn

To meet the duties of a social dawn.

Thus have they climbed thro ages gone to dust,

To save at last their cheap, ignoble lust.

So now they bluster to their holy task,

Tricked out in many a smug and shameless mask.

Frenzied they rush to reach the templed space

Where grin the idols: Pelf and Power and Place.

Here, at the doorway of all progress made,

Men pause to wipe their feet, their souls afraid.

Think you, some Persian rug outspreads its art?

Laugh lightly! 'Tis a woman's broken heart.

OBSERVATIONS AND COMMENTS

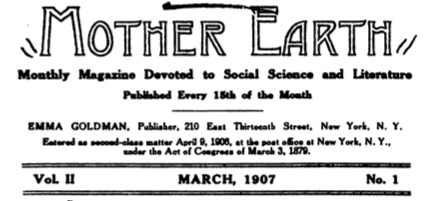

With this issue MOTHER EARTH enters upon her second year's journey, with colors flying. Last year's path was thorny, but not without fruitful results. The first anniversary was celebrated by more than four hundred friends from New York, Brooklyn and New Jersey, while those who could not attend gave evidence of their interest and appreciation by sending contributions.

We are grateful to our friends, and we promise to use our best efforts towards still further improving the educatiorial and literary standard of MOTHER EARTH. Those whose subscription has expired at the end of the first year will greatly aid us by sending in their renewals, so that we may know on how many of our old friends we may count.

* * *

The characteristic features of the Thaw case are: poverty, the power of money, venality of woman's love, man's greediness to possess. The central figure in this tragedy is a young woman—an article of sexual luxury, surrounded by prospective buyers. The purchaser regards her in the light of his private property, as he would his horse.

The young girl soon learns to play her part: the poverty-stricken mother looks upon the beauty of her (laughter as a future source of revenue; nothing offers such opportunities for "friendships" with rich men as the chorus.

Such men are seducers; yet still more so, the seduced. Woman's virtue, to them, is a tempting morsel; but while they are lavishing their money, they become the victims of subtle deceit Priding themselves on their victory over innocence, they are conquered by woman's cunning. Stanford Whites and Thaws can purchase bodies, but their combined wealth could not buy a single soul. That is the tragedy of such lives, as well as the comedy. Their victim is at the same time the avenger of her sex-slavery. Is she, the marketable thing, to be faithful? The master satiated, the slave is once more on the market. Serving White, she must still look out for another possible buyer. She meets Thaw—a simpleton, whose intellect would not suffice to make him a successful bootblack; but he is rich. He is a more promising catch than White; the latter, a man of "experience," is not so easily tricked. Thaw would guarantee the continuation of the life of luxury, to which she has become accustomed; he would even marry her, that she may realize her dream of an idle, rich, parasitic life.

Some marriages become prostitution; in this case, prostitution became marriage. The latter legalized the woman's swindle and caused the man's violent folly. But for the wedding, it would have been simply a case of prostitution, like a thousand other similar cases, characteristic of our good, moral society. Marriage, legalizing and complicating things, made the murder possible.

Because of the marriage—and the man's wealth—the girl became the legal property of Thaw; it was the latter's "duty" to guard the "honor" of the woman, not to speak of his own "honor." As lover, his honor was of no consideration; it became operative with the marriage. Her marriage forced the woman into greater deceit. She must no longer openly market her charms; tact and diplomacy are necessary to preserve marital decorum. She continues her relations with White; perhaps she even cares for him more than for her husband. The latter sees in her virtuous innocence persecuted; he believes implicitly her wild stories of the Bluebeard White. Finally he feels that morality demands vindication. He kills White and imagines that he has delivered his wife from her hated persecutor; he was "instrumental in the triumph of decency over vice."

The hangman condemns; the free-minded man strive& to understand. The question here is not who was right or who was wrong; rather, whether it is not necessary and possible to create a social atmosphere, where woman should cease to be a commodity, and mankind in general be delivered from the curse of money-greed and morality.

* * *

Why should the rich not rejoice and go to church? The latter teaches that "the rich and the poor we must always have with us," thus serving as the pillar of the parasitic existence of the wealthy. Why should the rich not love the State? The latter, by cunning and violence, guards their stolen wealth against the hungry producers.

The rich should also love the army; the latter secures to them possession of the Philippines and other islands; it tyrannizes over the natives and presses profits from them—for the rich.

But the poor—why should they care for these institutions? Those who continue to do so are the victims of a false education, misleading teachings and mental inertia.

* * *

Karl Marx taught his diciples that economics are the foundation of politics. His modern apostles have, how ever, reversed his teaching; their motto is, "Let us win political power; then we shall revolutionize the economic conditions." They have endeavored to transplant the center of revolution from the factory to Parliament, from the Street to the counting room. Hence the transformation of economic revolutionary Socialism into a political reform-movement. The strength of the latter depends on votes, not on revolutionaries. A parliamentary party must limit its activities to the constitution and laws of the country, thus aiding in upholding existing institutions. It cannot put itself outside of the law, since such a position would stamp all political activity on its part illogical and absurd.

Every government represents the legislative and administrative power of the bourgeoisie; the revolutionary proletarian must oppose it, rather than try to reform it.

Existing institutions can only be strengthened by the use of political power; to believe in their overthrow by such means is utopian. The social revolution begins where the belief in government and the present "order" ceases.

Herein lies the folly of parliamentary Socialists: at tempting to smuggle the social revolution under cover of reform, they merely succeeded in turning reformers and politicians.

By such means the German Social-Democracy had achieved great political "success." During many years it was the beacon of all parliamentary Socialists; soon it will serve as a sad example of what a true Labor Party should not be.

The January elections in Germany prove that the Socialistic power of political enlistment is exhausted. They have profited little by compromising with the Philistines, the lower middle class and the Clerical Party. They took good care to keep clear from the revolutionary and Anarchist element; indeed, their leaders were ever busy in keeping the party "pure." The energetic and progressive elements of the proletariat found the atmosphere of the party too stifling—they either left or were expelled. It was that very fear of offending popular prejudices that resulted in the Socialistic failure during the last elections.

The Socialists of Germany are between two fires—the revolutionary proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Gradually they must lose the confidence of the former, since their tactics condemn the working man to continue passively to suffer exploitation and oppression. Neither can they gain the confidence of the bourgeoisie, since the latter naturally prefers the safe representation of the fried parties—the Conservative and the Liberal. Revolutionary Socialists welcome the débacle of the parliamentary card-house. They have long since realized the fatality of political success; the mass, however, must first experience the reductium ad absurdum, ere it can find the proper solution.

* * *

The régime of the Tsar is daily becoming more anæmic. It is spilling the blood of the noblest children of Russia in thick streams, but the precious fluid serves to strengthen the revolution and to make Tsarism weak and lifeless. Lacking internal vitality, the Russian despotism believes to have found a much-needed stimulant in the Duma. The latter is to save the knout; it should bring "order" out of the existing chaos and rehabilitate an ignominious government.

In case of success, European and American financiers would regain their confidence in the autocracy, and more cash would be forthcoming to aid in suppressing the revolution.

* * *

Ideals do not pay. If we happen to possess any remnants of old convictions, we should put them on the shelf with other bric-a-brac, to be occasionally admired in a pensive mood.

Is it not a proof of a "fine soul" to talk of the asinineties of one's youthful days? When business is slack, it is rather pleasant to recollect "those wild things." Of course, one must not forget himself so far as to call back to life old ideals and, perchance, become active in their behalf.

Thus philosophise the "wise," the "practical," the matter-of-fact people; they shrug their shoulders, assuring us that life must be taken as it is, not as it should be. But what is life? Life spells hypocrisy; the world is peopled with sneaks, renegades and cowards. A few thousand more or less of this calibre—what does it matter?! The competition among them is constantly growing more intense; soon the ex-idealist realizes that he has been doubly cheated: he has bartered the best part of himself for profit, and now he finds himself sadly disappointed in his expectations.

THE RED MONTH

THERE are days in history that should be prohibited I by governments; days of an exciting, destructive character, possessing the power of rousing the elemental forces of men into activity; days apparently unrelated to the rest of the year.

Our immigration laws prohibit the landing of persons who disbelieve in organized government, thus barring Anarchists from our joyful shores. Alas, what an in effectual method of keeping out "obnoxious elements"! To properly protect the subjects of this country against the spirit of rebellion, it is necessary to banish the historical dates, when organized governments have been forcibly overthrown.

Ye Legislators, to the front! You have a great task to perform. 'Tis of little avail to expel the John Turners, so long as the lessons of revolutionary history— and their pernicious ideas—are accessible to the people. March is the red month in the modern history of Europe. America has not as yet experienced such dangerous events;—too dangerous for power and authority. The war of 1776 was, after all, but a territorial, not a national revolution: the refuse of all countries, thrown into the American pot, could hardly be called a Nation. The Monroe doctrine existed before it was conceived by Monroe. "English lords may continue to rob the Irish peasants and oppress the industrial slaves of Lancashire and Manchester, as they please; on American soil we can exploit labor oirse1ves." Such were the arguments of the newly-baked American patriots, who saw in this country the greatest source of wealth and power. European revolutions had a different aspect; there the Nations were swept by the fires of social and economic regeneration.

March eighteenth and nineteenth, 1848, arc memorable in the history of Prussia. Citizens, students and work men of Berlin fought the hireling army of the government, on barricades. Tue throne began to totter. The people carried their fallen dead before the palace and demanded that the king pay his respects to the noble dead. The storm of March had performed a miracle: for once the king obeyed the people.

The Revolution spread through Germany, Austria and France. Unfortunately, however, the revolutionarylo THE RED MONTH triumph was of short duration; within a few months the fatal grip of the reaction stifled every free expression. To-day, the revolution of 1848 seems quite dilettant. In their grand fight for a noble cause the people had neglected the most important thing; they failed to destroy the very basis of all tyranny—its material existence: they had too much reverence for property. The treasury remained in the hands of the reactionaries; with sufficient means to buy uniformed assassins, the government speedily subdued the people. As usual, Labor proved the greatest victim; it achieved a few shallow political rights, remaining economically enslaved as before.

Twenty-three years later another March storm swept the rotten foundations of Society—the Paris Commune. On the eighteenth of March, 1871, the proletariat of Paris rose in arms against the dictatorship of the abominable wretch Thiers, who had attempted to force a new monrchy upon poor, exhausted France, still bleeding from the wounds made by German bayonets.

Men, women and children rushed into the streets and took possession of arms and ammunition; within a few hours the Commune was proclaimed and the red banner displayed from the Hotel de Ville, the City Hall. What joy I What inspiration I This time it was no mere political uprising; the people demanded not a mere change of government, but social and economic reconstruction. The grand ideals of Socialism, Communism and Anarchism had inspired the people with new hope. Again it was the stupid respect for property that finally caused the fall of the Commune, resulting in the terrible slaughter of thirty thousand people.

But the Red Month was not in vain. It has taught us important lessons. No government, whatever reform- mask it may affect, can ever banish the spirit of rebellion from the hearts of the exploited and oppressed millions. The hand of the sacred month of March has written this unforgetable lesson, in letters of blood, upon the minds of those who think.

And we have learned, further, that if the coming revolution is to be successful, the revolutionaries must emancipate themselves from their old traditions, their reverence for stolen property, their moral notions.

May the lessons of the past guide us in the comingstorms of March.

HUGH O. PENTECOST

By VOLTAIRINE DE CLEYRE.

EIGHTEEN or nineteen years ago, away out in a sleepy little Michigan town, there fell into my hands a tiny bit of a paper "no bigger than a man's hand"; there were only four sheets of it, but every word was vibrant with life and power. It was written by Hugh O. Pentecost and T. B. McCready, and at this hour I feel my eyes opening wide again as they did that morning with the light and the movement in the swinging lines. They were Single-Taxers then, but with an alarming freedom in their handling of it that must have made the orthodox Georgeites tremble for what was likely to come next; and for what did come next. From week to week the little paper grew in thought, and grew in size, and grew in force. McCready wrote comments on life as it passed, and Pentecost delivered speeches which were printed; and it was often hard to tell who said the best things and said them best. One great quality they had in common: their thoughts were naked and not ashamed. They were moving towards a rising sun, and if from week to week the light broke farther, wider, higher, and things came out with a different face than they had appeared in the semi-twilight of a month before, neither McCready nor Pentecost shrank from owning it; and men who were thinking along with them felt not the respect of a pupil for a teacher, but the free comradeship of fellow-seekers. There was such a world of good humor in it, such a frankness, such a fearlessness in reversing themselves! and such fire in it all!

Only,—even those of us who were already Anarchists, and who saw things coming our way, naturally with satisfaction, could not but feel startled at times, and a little dubious, too, at the unwonted speed the Twentieth Century was making. Willy-nilly, the question would intrude: "Can the man who so easily, so rapidly changes his mind, have had time to ground himself well? Will not he who so readily deserts his old position desert the new as readily?"- It was at the time this question was obtruding itself most insistently upon me, in spite of the genuine delight I felt in reading Pentecost's speeches,

12 HUGH O. PENTECOST

that my first opportunity to hear him came. I remember so well the remarks he made concerning those self-same lightning changes, which, apparently, others must have questioned him about. "People say that I change my mind too rapidly. Why, it is perfectly delightful to find out you have mind enough to change !" Still we kept on shaking our heads over our own good fortune (for Pentecost had now become unequivocally opposed to all law, and while he never called himself an Anarchist in the paper, he even went as far as that in a private letter which I have seen, wherein he said: "Any one who advances logically along the lines that I have done, must land in Anarchy, and that is where I have landed.") I recall that in discussing Mr. Pentecost with Dr. Gertrude Kelly, not long after this, she expressed her opinion that be was an "immoral character," in that being himself in a developing state of mind, not certain of himself, he nevertheless undertook to teach others; that he pronounced himself before knowing what he was talking about, and upset other people's minds without giving them clear ideas. Remembering all this now, I cannot help thinking that Dr. Kelly was right, and yet I am unspeakably glad that Pentecost and McCready spoke when they did and as they did. The Twentieth Century was the most interesting type of the "free platform" we have seen in this country within my knowledge; it blew like a breath out of the world of the making of things, it bubbled with life, and was indifferent to consistency. It had grown from the tiny paperlet to a sixteen-page journal, and never lost its principal character of eager questioning.

Then there came a heavy blow: McCready, sunny McCready, of the laughing words; funny, McCready, with his gay tilt-riding at the ponderous Knights of the Present Order; tender McCready, with the brimming sympathies; loving McCready was dead, and half the light of the "Twentieth Century" went out.

Nay, more than half. For already there was creeping into the editorials of Pentecost a lassitude, a heaviness, that told of the dying fire. The contributors gave as before, and there were many good ones. But the peculiar glory of the paper, its brilliant editor was somehow a little spiritless. Words went around. The man had sacrificed too much; he had been a wealthy preacher of a wealthy church. He had forsaken wealth to follow his ideals of truth, and though the crowd that followed him had grown larger and larger, it was not the crowd that could give him the material things he had once enjoyed. And then we heard that Mr. Pentecost was studying law; and then that he had given up the "Twentieth Century." And then we heard little more of him till the black thing fell. And when it fell I was glad that McCready was dead and would never know. The daily papers told us first, but of course we did not believe them. We waited till we saw it all in the "Twentieth Century" itself, and then we had to know that Hugh O. Pentecost, the man who had so effectually demonstrated the iniquity of laws, had mocked at law-worship, done his best to destroy it, had sought and all but received an Assistant District Attorneyship. All but. It was his own ghost that saved him; for the daily papers of the opposition had dragged out the files of the "Twentieth Century," hunted through them for the most Anarchistic of his speeches, reprinted and spread them broadcast—unmindful that they were doing the Anarchists good service thereby, so that they won their point —and asked the voters: Is this the man for a District Attorneyship? So great was the pressure brought upon the chief who had promised him the position, that he was compelled to retract his promise to Pentecost, after the election, and when the latter came prepared to take the oath of office he was met by a definite refusal. Thereupon appeared Mr. Pentecost's recantation of heresy. In all my life I have never read a document so utterly devoid of human dignity, so utterly currish. There is a piece of detestable slang which is the sole expression fit for it: "The Baby Act." Not only did Mr. Pentecost renounce his former beliefs in liberty, but he took refuge in the pitiable explanation that he, a cloud-land dreamer, had been misled by his innocence into the defense of Parsons, Spies, etc., who, now he had been convinced, had been properly enough hanged. Poor, delicate lamb deceived by ravenous wolves! That was the tenor of the story. Had it been all true, a man would have bitten out his tongue rather than have told such truth. All this is many years ago, and gentler spirits than mine have overlooked and almost forgotten it, in the redemption of his after years. But when the sum of his life is cast up, Justice says, let it not be for gotten that he had within him the Benedict Arnold, and had the times been such as are in Russia now, he would have sold the lives of men as then he sold his conscience for a mess of pottage.

"After Death the Resurrection." That recantation was the putrefaction of a dead soul. There came a quickening. For a few years he was silent; then one day we heard that Pentecost was speaking—again back on the side of liberalism! I confess I heard it with rage. "Let him have the decency to keep still," I said. "If he is really sincere, let him be a radical, long enough to prove his sincerity, without talking." Others said I was too harsh, and I think they were right. But I could not forget that sentence about the Chicago men.

For all the years since 1892 I had not seen him. I avoided him as sedulously as I could whenever requests for speeches would have brought us in contact. To all descriptions of his splendid addresses I sneered back: "What is he now?" At length it fell out, about a year ago, that we were both to address a Moyer and Haywood protest meeting in Philadelphia. In such a cause I did not think I had a right to refuse to speak; so I swallowed my dislike, but remarked to the chairman, Geo. Brown, "Don't you steer me up against Pentecost. I don't want to have to speak to him." Geo. Brown is nothing if not mischief-loving. He wanted to see the fur fly. Incidentally he wanted to tell Pentecost that he himself was still a little sore over that recantation, but, while fond of seeing other people rage, he dislikes to say disagreeable things. So he did just what I told him not to do. I am glad now that he did. There was nothing for it but to say what I felt. I remember the hurt look, hurt and surprised, on Pentecost's face when Brown said, "Here is a lady who has a grudge against you." I plunged in; his mouth and eyes saddened, inexpressibly. "The District Attorneyship? Yes, it was all wrong, all wrong. But wasn't that a long time ago?" I admitted it was; but was that an excuse? No, it was no excuse; there could be no excuse. He knew that; he didn't offer any; his mind had been in a condition of moral slump, and influences had been used on him; but he knew that didn't justify him. "Of course, If I had got it, I would have accepted and gone on with it—" I interrupted him: "It was your luck, Mr. Pentecost, that you didn't get it."—"It was. No one realized that better than I. No one was happier than I that I didn't get it.—It was through the efforts of Mrs. Pentecost that the offer had been obtained."—"And what you said of your having been deceived into the defense of Parsons and the rest ?"—He didn't remember having worded the matter quite so pitiably as I said; but what he meant was that lie had been misinformed; he had thought these men had never preached force or counseled it, while later information had led him to believe there had been a conspiracy, as the State contended. However, for any evidence that went before the court, the men were never proven guilty, and that he stood by, as he had stood in the old days of '86, when, to the best of his belief, he was the first public man who had spoken in their defense. He seemed to take great satisfaction in that memory, and repeated it on the platform later on. As for the rest, he bad done his best. He had kept silent for a while; and now for ten years he had worked in New York, and he thought those who knew his work would bear witness to his sincerity. What more could he say?

And what more could he say? When a man has done wrong, and owned it, and done his best to retrieve him self, he has done all. My bitterness melted, and we shook hands then.

His speech was, as always, strong, graceful, effective. But it was the trained lawyer speaking; not the old in spired prophet of liberty. The menace in his final sentence showed that if he had once deprecated forcible resistance as preached by the Chicago men, he had shifted that ground, too; for he said that if the powers of Idaho refused fair trial to these men, annihilated all attempts at peaceable justice, then—"LET THEM TAKE THE CONSEQUENCES."

Before he went he said to me: "I am glad we have had this talk. I would not want you to feel unkind to- -wards me, for you have not a better friend than I am." I give the sentence, because it shows his personal mag