PUBLISHED BY

EMMA GOLDMAN

Office PRICE

210 E. 13th ST. N. Y. City 10c PER COPY

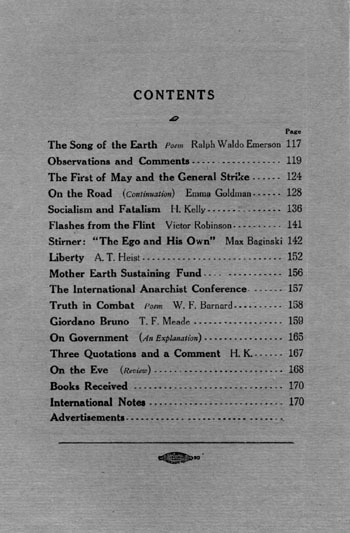

CONTENTS

| The Song of the Earth Poem Ralph Waldo Emerson | ... | 117 |

| Observations and Comments | ............................. | 119 |

| The First of May and the General Strike | .............. | 124 |

| On The Road (Continuation) Emma Goldman | .......... | 128 |

| Socialism and Fatalism H. Kelly | ...................... | 130 |

| Flashes from the Flint Victor Robinson | ............... | 141 |

| Stirner: "The Ego and His Own" Max Baginski | .......... | 142 |

| Liberty A. T. Heist | .................................. | 152 |

| Mother Earth Sustaining Fund | ......................... | 156 |

| The International Anarchist Conference | ............... | 157 |

| Truth in Combat Poem W. F. Barnard | ............. | 158 |

| Giordano Bruno T. F. Meade | ........................... | 159 |

| On Government (An Explanation) | ................... | 165 |

| Three Quotations and a Comment H. K. | ................. | 167 |

| On the Eve (Review) | .............................. | 168 |

| Books Received | ....................................... | 170 |

| International Notes | .................................. | 170 |

| 10 Cents per Copy | | $1 Year |

|

Monthly Magazine Devoted to Social Science and Literature

Published Every 15th of the Month

EMMA GOLDMAN, Proprietor, 210 East Thirteenth Street, New York, N. Y.

Entered as second-class matter April 9, 1906, as the post office at New York, N. Y.,

under the Act of Congress of March 3, 1879.

Vol. II MAY, 1907 No.3

|

THE SONG OF THE EARTH

By Ralph Waldo Emerson

Bulkely, Hunt, Willard, Hosmer, Merian, Flint,

Possessed the land which rendered to their toil

Hay, corn, roots, hemp, flax, apples, wool and wood

Each of these landlords walked amidst his farm,

Saying, "'Tis mine, my children's and my name's.

How sweet the west wind sounds in my own trees!

How graceful climb those shadows on my hill!

I fancy these pre waters and the flags

Know me, as does my dog: we sympathize ;

And, I affirm, my actions smack of the soil."

Where are these men? Asleep beneath their grounds;

And strangers, fond as they, their furrows plough.

Earth laughs in flowers, to see her boastful boys

Earth-proud, proud of the earth which is not theirs;

Who steer the plough, but cannot steer their feet

Clear of the grave.

They added ridge to valley, brook to pond,

And sighed for all that bounded their domain;

"This suits me for a pasture; that's my park;

We must have clay, lime, gravel, granite-ledge,

And misty lowland, where to go for peat.

The land is well, - lies fairly to the south.

'Tis good, when you have crossed the sea and back

To find the sit-fast acres where you left them."

Ah! the hot owner sees not Death, who adds

Him to his land, a lump of mould the more.

Hear what the Earth says:-

EARTH-SONG

"Mine and yours;

Mine, not yours.

Earth Endures;

Stars abide-

Shine down in the old sea;

Old are the shores;

But where are old men?

I who have seen much,

Such have I never seen.

"They lawyer's deed

Ran sure,

'In tail,

To them, and to their heirs

Who shall succeed,

Without fail,

For evermore.'

"Here is the land,

Shaggy with wood,

With its old valley,

Mound and flood.

But the heritors?

Fled like the flood's foam.

The lawyer, and the laws,

And the kingdom,

Clean swept herefrom.

"They called me theirs,

Who so controlled me;

Yet every one

Wished to stay, and is gone.

How am I theirs,

If they cannot hold me,

But I hold them?"

When I heard the Earth-song,

I was no longer brave;

My avarice cooled,

Like lust in the chill of the grave.

* * *

OBSERVATIONS AND COMMENTS

As long as the capitalists of Europe and America could, with the aid of their respective governments, carry their "civilization" into Asia and force the latter's truly cultured people to buy their shoddy wares, there existed no yellow peril. Only when the "heathens" began to practically apply the lessons taught them by their white "benefactors"; when they, too, began to propagate civilization -- lo! suddenly we perceived the yellow peril.

"Guard your most sacred possessions, ye nations of Europe!" cried the German Emperor, and the international boodlers applauded unanimously. Many working-men, especially those of America, joined in the cry; even some revolutionists were deluded into belief that the competition of Asiatic labor was dangerous to their ideas. How unjustified this fear has fully been demonstrated within the last few years by the remarkable spreading of social revolutionary ideas among the Japanese and Chinese. The intellectuals of these nations are as familiar with modern radical ideas as the people of America and Europe. The labor question is now no less acute in those countries than with us.

A very hopeful sign of the times is the recent organization of the "Social Revolutionary Party of Japanese in America," whose aim it is to enlighten their countrymen with regard to existing social conditions and to prepare them for the social revolution.

Herewith we publish the proclamation of the new organization, a remarkable document, which indicates that the American workingmen have a great deal to learn from their "heathen" brothers:

"We proclaim to the people of the whole world the organization of the Social Revolutionary Party of Japanese in America.

Who says that labor is divine, while a few people are fed and clothed well and millions are suffering from poverty and hunger?

What is life for, when one man takes away the rights and liberty of millions that he may live in luxury and ease?

What is the dignity of a nation when the lives of millions are sacrificed in war to satisfy a few men's ambition and vanity?

Yes, labor is intolerable, life is miserable, the nation is cruel, and society is unjust.

The cries of the sufferers all over the world are increasing day after day, and the enthusiastic attempts to abolish these torments and to try to secure true liberty and happiness and peace are increasing month after month.

How can a man who has heart and soul look at suffering humanity without a feeling of sympathy or a desire to assist in the alleviation of the wrongs?

It is our duty to revolutionize this unjust system of society and make it a beautiful, free, happy one, both to the honor of our forefathers, and for the benefit of our sons. It is not only our duty, but it is our right.

The purpose of our revolutionary society is to realize this fact, and to discharge this duty and secure our rights.

Come, those who are interested, and join us. Do not hesitate!

Our Program:

- We shall abolish the industrial, economic competitive system of to-day, which breeds pauperism, and let the people who own the nation's wealth.

- We shall endeavor to destroy traditional and superstitious ideas of class lines, and will try to insure equal rights for all.

- We shall endeavor to abolish racial prejudice and learn to realize the true meaning of the brotherhood of men.

- In order to accomplish the above stated purposes we recognize the necessity of uniting with the comrades of the world."

* * *

If anything more was necessary to convince the American public of the existence of a capitalistic conspiracy to hang Moyer, Haywood and Pettibone, and destroy the Western Federation of Miners, the high-handed interference of Theodore Roosevelt has accomplished that.

To curry favor with the pirates whose stolen millions sent him to the White House, our political desperado did not hesitate to stoop to the use of his official position against the Idaho defendants. Such base attempts to influence justice have seldom been witnessed outside of Morocco and Turkey.

We say, to influence justice ; because the private opinion of a professional politician as to the moral worth of the representatives of revolutionary ideas is a matter of entire indifference to the latter. It is self-evident that the chief lackey of the plutocrats cannot consider the opponents of the latter as anything but "undesirable citizens." There are many citizens, however - and by no means the worst - who look upon the White House parasites as highly undesirable citizens.

It is time that the American people, and especially organized labor, should realize that the White House is the very last place to look for justice, a "square deal," or even common decency.

* * *

We mourn the tragic fate of William McLaughlin - better known as "Billy" -late Inspector of Police, Chief of the New York Detective Bureau, and Head of the "Anarchist Squad," of recent creation. Yesterday a power in the land ; to-day a mere Captain of Westchester, familiarly known as Goatville, with nothing to do but sign his name in the blotter twice a day. The salary is a paltry two thousand five hundred a year, and but little graft. The Sun, whose editor claims friendship with "Billy," informs us that the former detective is rich - his wealth, no doubt, saved from the yearly salary of three thousand five hundred - and that he is expected to resign at once. Others say that "he is game and will stick it out." All of this is very sad for a man who can buy twenty-thousand dollar houses and live like a bank president on a salary of three thousand five hundred a year. Such a genius deserves to be chancellor of the exchequer of a South American Republic. Alas, poor William!

* * *

Our friend Luigi Galleani was tried during the last week of April for alleged participation in the Paterson riots of 1902. We are happy to state that the trial resulted in a disagreement, seven jurymen voting for conviction and five for acquittal. We do not think that the District Attorney of Paterson will seek new laurels by bringing Galleani to trial again. It is to be hoped that he will not succeed in finding twelve men to send our innocent brother to prison.

On the heels of the trial comes the information that William McQueen - whose five-year sentence for "complicity" in the Paterson troubles had almost expired - was pardoned on condition that he leave at once our hospitable shores. The Paterson capitalists and their political lackeys may now rest in peace.

* * *

Maurice Donnay, an enfant terrible of French literature, has recently been elected member of the Academic Francaise. Loyalty, rather than literary merit, is nowadays the key that unlocks the door of immorality ; mere loyalty is often sufficient ; merit alone - never. Maurice Donnay is one of the few possessing both.

Besides Antaloe France and Jules Lemaitre, he is now the only artist in the Academy who considers industrious erudition, alexandrines of proper measure and fine sounding parliamentary speeches as meritorious literary productions.

Ten years ago, however, he would have knocked for admittance in vain. All his poetic finesse, his manifold talents and power of ingenious observation did not suffice to open the door, until he had conclusively proven by one of his recent mediocre plays that he was eligible to immortality.

His receptive soul must often suffer tortuous hours by the incarceration of his wild spirit within the confines of academic respectability. In truth, but once has he succeeded in taming down his genius to the strict requirements of a conventional play. In all his following works his artistic spirit soon manifested itself by rising above all literary dogmas and puritanic morality.

The academic sedateness demanded by the mossy institution from its Immortals will hardly prove a sufficient guarantee against an occasional "bad break" - no more than Donnay's erudite engineer training prevented his public appearance as chansonnier in the Chat Noir of Rodolphe Salis.

The eternal fitness of things: the p&eolig;ns of peace sung by professional exponents of war.

The peace farce of recent date was as fiendish a caricature of the Brotherhood of Man as Satan could desire. A glance at the list of participants is sufficient to characterize the sincerity of those friends of peace.The parvenu steel king in the role of chief peace-maker, - ye gods, what a spectacle!

Having had his praises sung on Founders' Day, at Pittsburg, the hero of Skibo and Homestead, this chief beneficiary of the war on classes, came to New York to witness his triumph as king of peace. As such he was felicitated by his imperial brothers, Oily Bill and Terrible Teddy, and decorated by the French Government with the cross of the Legion of Honor. This honor, however, is now of such questionable quality that it may properly be said of an honest man thus decorated : "He has been dishonored with the Legion of Honor."

* * *

In the sign of prosperity.

On the benches in Madison Square cower, chilled, human debris - ragged, dirty, hollow-eyed, mere caricatures of man ....

It is not permitted to sleep in the parks. Soon comes the night stick, awakening the dozing ; the policeman drives the frightened wretches out of the park. They go, resigned in the abyss of despair, further - further!

At Union Square the cruel performance is repeated. The nearer we approach the lower part of the city, the more pronounced and heartrending the misery and suffering. From foul-smelling alleys and filthy hallways there comes the sound of heavy breathing and low coughing. The dark steps of the railroad tunnel are plastered with the forbidding figures of unemployed and homeless - men for whom there is no room in all the forest of houses and who cannot afford the price of a night's lodging ; men to whom work is a luxury, unattainable by those run down at the heels and whose shoes are tied with strings ; men past vice or virtue ; men who have long since forgotten to live and are too misery-stupified to cross the threshold of the land of the dead.

In the sign of prosperity.

* * *

THE FIRST MAY AND THE GENERAL STRIKE

WITH the Spring awakening of Nature the dormant energies of the people are revivified - the oppressed feel their self-consciousness and the joy of combat stirring within them.

Stormy March - the red month of revolution ; stirring May - the fighting month of the proletariat striving for independence.

The basic revolutionary idea of the first of May has characterized all the battles of labor in modern times, and the historic origin and development of that idea prove its great significance for the labor movement.

The May idea - in the relation of its revolutionary spirit to labor struggles - first manifested itself in the economic battles of the Knights of Labor. The final theoretical aim of that organization - founded by Uriah S. Stephens and fellow workers in 1869, and bearing a pronounced radical character in the beginning of its history - was the emancipation of the working classes by means of direct economic action. Its first practical demand was the eight-hour day, and the agitation to that end was an unusually strenuous one. Several strikes of the Knights of Labor were practically General Strikes. The various economic battles of that period, supported by the American Federation of Labor during its young days, culminated , on the first of May, 1886, in a great strike, which gradually assumed almost national proportions. The workingmen of a number of large cities, especially those of Chicago, ceased their work on that day and proclaimed a strike in favor of the eight-hour day. They thus served notice on their capitalistic masters that henceforth they will not be submissively exploited by the unlimited greed of the capitalists, who had appropriated the means of production created by the many generations of labor, thus usurping the position of masters - the kind masters who had cordially leave labor the alternative of either prostituting their brawn or dying with the families of starvation.

The manly attitude of labor in 1886 was the result of a resolution passed by the Labor Congress held at St. Louis, one year previously. Great demonstrations of a pronounced social revolutionary character took place all over the country, culminating in the strike of two hundred thousand workingmen, the majority of whom were successful in winning the eight-hour day.

But great principles of historic significance never triumph without a blood baptism. Such was also the case in 1886. The determination of the workingmen to decide to sell to the purchasers of labor was looked upon by the exploiters as the height of assumption, and condemned accordingly. Individual capitalists, though unwilling, were nevertheless forced to submit to the demands of organized labor ; perceiving, however, in the self-respecting attitude of the working masses a peril threatening the very foundations of the capitalistic economic system, they thirsted for revenge ; nothing less would satisfy the cannibalistic masters but human sacrifices : the most devoted and advanced representatives of the movement - Parsons, Spies, Engel, Fischer and Lingg - were the victims.

The names of our murdered brothers, sacrificed to propitiate an enraged Moloch, will forever remain indivisibly linked with the idea of the first of May. It was the Anarchists that bore the brunt of those economic battles.

In vain, however, did organized capital hope to strangle the labor movement on the scaffold ; a bitter disappointment awaited the exploiters. True, the movement had suffered an eclipse, but only a temporary one. Quickly rallying its forces, it grew with renewed vigor and energy.

In December, 1888, the American Federation of Labor decided to make another attempt to win the eight-hour day, and again by means of direct economic action. The strike was to be initiated by a gigantic demonstration on the first of May, 1890.

In the meantime there assembled at Paris (1889) an International Labor Congress. A resolution was offered to join the demonstration, and the day which three years previously initiated the eight-hour movement became the slogan of the international proletariat, awakened to the realization of the revolutionary character of its final emancipation. Chicago was to serve as an example.

Unfortunately, however, the direction was not followed. The majority of the congress consisting of political parliamentarists, believers in indirect action, they purposely ignored the essential import of the first of May, so dearly bought on the battlefield ; they decided that henceforth the first of May was to be "consecrated to the dignity of labor," thus perverting the revolutionary significance of the great day into a mere appear to the powers that be to grant the favor of an eight-hour day. Thus the parliamentarists degraded the noble meaning of the historic day.

The first of may "consecrated to the dignity of labor!" As if slavery could be dignified by anything save revolutionary action. As long as labor remains mere prostitution, selling its producing power for money, and as long as the majority of mankind are excluded from the blessings of civilization, the first of May must remain the revolutionary battle cry of labor's economic emancipation.

The effect of the Paris resolution soon manifested itself : the revolutionary energy of the masses became dormant ; the wage slaves limited their activity to mere appeals to their masters for alleviation and to political action, either independent of, or in fusion with, the bourgeois parties, as is the case in England and America. They quietly suffered their representatives in Parliament and Congress to defend and strengthen their enemy, the government. They remained passive while their alleged leaders made deals with the exploiters, hobnobbed with the bourgeois, and were banquetted by the exploiters, while oppression steadily grew in proportion and intensity, and all attempts of the wage slaves to throw off their yoke were suppressed in the most merciless manner.

Only a small minority of the working class, especially in the Latin countries, remained true to the revolutionary spirit of the first of May ; but the effect of their noble efforts was materially minimized by their international isolation, repressed as they were by the constantly growing power of the governments, strengthened by the reactionary political activity of the labor bodies.

But the disastrous defeats suffered by labor on the field of parliamentarism and pure-and-simple unionism have radically changed the situation in recent years. To-day we stand on the threshold of a new era in the emancipation of labor : the dissatisfaction with the former tactics is constantly growing, and the demand is being voiced for the most energetic weapon at the command of labor - the General Strike

It is quite explicable that the more progressive workingmen of the world should hail with enthusiasm the idea of the General Strike. The latter is the truest reflex of the crisis of economic contrasts and the most decisive expression of the intelligent dissatisfaction of the proletariat.

Bitter experience has gradually forced upon organized labor the realization that it is difficult, if not impossible, for isolated unions and trades to successfully wage war against organized capital ; for capital is organized, into national as well as international bodies, co-operating in their exploitation and oppression of labor. To be successful, therefore, modern strikes must constantly assume ever larger proportions, involving the solidaric co-operation of all the branches of an affected industry - an idea gradually gaining recognition in the trades unions. This explains the occurrence of sympathetic strikes, in which men in related industries cease work in brotherly co-operation with their striking bothers - evidences of solidarity so terrifying to the capitalistic class.

Solidaric strikes do not represent the battle of an isolated union or trade with an individual capitalist or group of capitalists ; they are the war of the proletariat class with its organized enemy, the capitalist regime. The solidaric strike is the prologue of the General Strike.

The modern worker has ceased to be the slave of the individual capitalist ; to-day, the capitalist class is his master. However great his occasional victories on the economic field, he still remains a wage slave. It is, therefore, not sufficient for labor unions to strive to merely lessen the pressure of the capitalistic heel ; progressive workingmen's organizations can have but one worthy object -- to achieve their full economic stature by complete emancipation from wage slavery.

That is the true mission of trades unions. They bear the germs of a potential social revolution ; aye, more - they are the factors that will fashion the system of production and distribution in the coming free society.

The proletariat of Europe has already awakened to a realization of his great mission ; it remains for the American workers to decide whether they will continue, as before, to be satisfied with the crumbs off the board of the wealthy. Let us hope that they will soon awaken to the full perception of their great historic mission, bearing in mind the battle scars of former years. Especially at this time, when organized capital of America - the most powerful and greedy of the world - is again attempting to repeat the tragedy of 1887, American labor must warn the overbearing masters with a decisive "Thus far and no further!"

* * *

ON THE ROAD

By Emma Goldman

(Continuation)

CHICAGO. City of the greatest American crime! City of that black Friday when four brave sons of the people were strangled to death - Parsons, Spies, Engel and Fischer, and you young giant who preferred to take your own life rather than allow the hangman to desecrate you with his filthy touch. You noble free spirits who walked along the open road, believing its call to be "the call of battle, of rebellion." 'Tis therefore you went "with angry enemies, with desertion."

O for the indifference, the inertia of those whose cowardice permitted you to die, to be strangled - the very people for whom you had given your life's blood.

O city of shame and disgrace! City of gloom and smoke, filth and stench. You are rotten with stockyards and slums, poverty and crime. What will become of you on the day of reckoning, when your children will awaken to consciousness? Will their battle for liberty and human dignity cleanse your past? Or will they demolish you with their wrath, their hatred, their revenge for all you have made them endure?

As my train neared this hole, bellowing suffocating smoke and dust, covering the sky with a dark, gloomy cloth, on the morning of the eighteenth of March, I thought of you, Paris. Great, glorious Paris! Cradle of rebellion, mother of that glad, joyous day, thirty-six years ago, when your flying colors proclaimed brotherhood and peace in the grand spirit of the Commune. What a contrast between you and Chicago! The one inspiring, urging on to rebellion and liberty ; the other making her children mercenary and indifferent, clumsily self-satisfied. What a contrast! What an awful contrast!

I arrived at Chicago at the high tide of politics, the various parties wrangling, huckstering and wrestling for political supremacy, each claiming to stand for a principle : the greatest good of the people.

What Bernard Shaw says of the English in "The Man of Destiny" holds equally good with us in this country : "When the Englishman wants a thing, he never tells himself that he wants it. He waits patiently till there comes into his mind, no one knows how, a burning conviction that it is his moral and religious duty to conquer those who have got the thing he wants. He is never at a loss for an effective moral attitude. As the great champion of freedom and national independence, he conquers and annexes half the world and calls it colonization. When he wants a market for his adulterated Manchester goods, he sends a missionary to teach the natives the gospel of peace. The natives kill the missionary, he flies to arms in defence of Christianity, fights for it, conquers for it, and takes the market as a reward from heaven. In defence of his island shores he puts a chaplain on board his ship, mails a flag with a cross onto his top gallant mast and sails to the ends of the earth, sinking, burning and destroying all who dispute the empire of the seas with him. You will never find an Englishman in the wrong. He does everything on principle. He fights you on patriotic principles, he robs you on business principles, he enslaves you on imperial principles, he bullies you on manly principles."

No better picture could be drawn of our own good people, especially our politicians Of course they do not want the job of mayor, governor or president ; of course they do not want to get fat as the proverbial seven cows ; it is only for a principle that they enter politics, for the dear people's sake, for municipal ownership's sake, for the sake of purifying our bad morals, for good government, for child labor laws, factory improvement, for anything and everything, only not for their own sake. 'Tis for the sake of principle our politicians fight, lie and abuse one another ; for the sake of principle they invest their money in land robbery, in cotton mills where the children of the dear majority are forced to work under the industrial lash, or in stockyards and packing houses where human beings are made to rot in filth.

For the sake of principle liberals, the Single Taxers, have made a compact with the Democratic Party, hailing Dunne, Hearst and others of their caliber as the Messiahs of the people, and indulging in the same cheap methods of abuse and attack. One of our Single Tax brothers was elated over the discovery that his opponent lived with a "nigger." "We'll use it against him. It is sure to kill his chances," said our "liberal" friend, and no doubt it is. Just think, advanced people prying into the private life of a man and publicly dissecting it for the sake of a political job, - I beg your pardon, for the sake of principle. How coarse, how vulgar "principle" has made man.

And our Socialist friend, is he not ready to string up anyone who disputes "economic determinism" and "the materialistic conception of history" ? For the sake of his principle he will kick anyone out of the party who dares doubt the infallibility of political action ; he will denounce us as dynamiters, when we venture to suggest some other method. For the sake of principle the Socialistic paper of Chicago devotes its front page to the discussion of "gowns for the ladies," and a Socialistic candidate appeals for votes on the ground that he has a good law practice and an income of a hundred thousand dollars. And the majority goes into the trap and allows itself to be humbugged - for the sake of a principle.

While in Chicago I delivered nine lectures before various nationalities - Jewish, Bohemians, Danish, not to forget of course the dear, fortunate natives who make the Social Science League their headquarters. Whether it was due to the subject, "The Revolutionary Spirit of the Modern Drama," or to the innate curiosity of the Americans, I do not know ; at any rate the meeting at the Masonic Temple was the largest and most interesting. Two real life professors from the Chicago University, quite a host of students from the same institution, as well as lawyers, politicians and workingmen packed the hall. Great strides must have been made in the last few years to bring out instructors and students from the Rockefeller College. It is not so very long ago that Tolstoi's picture was turned face to the wall because he dared criticise the endower of that hall of learning.

Some naive people were so enthusiastic over my lecture that they suggested to one of the professors that he invite me to the University to repeat my lecture. Alas, they forgot the "principle" for the sake of which the good professor could not invite the Anarchist, Emma Goldman, to the College. Probably he thought that at the sound of Anarchism the University buildings would crumble to pieces, as the walls of Jericho did at the sound of the Jewish trumpet. No one can blame the professor - "principle" before freedom of knowledge.

Life in Chicago has always been hateful and trying to me, but the great kindness at the home of my dear comrades, Annie and Jack Livshis, and especially the untiring goodness and the fine tact at the discretion of the Anarchistic Mother, Annie, helped to overcome my aversion to the jungle city.

Cincinnati. The old sensational speculations as to whether I will or will not be allowed to speak in that city greeted me in the newspapers when I arrived. Madam Alice R. Longworth living on Walnut Hill, it was quite reckless of the city fathers to alow dangerous utterances at Cincinnati. However, Anarchism has been heard at three large meetings, and Walnut Hill is still intact. America is full of parasites - Anarchism has greater things to do than to bother about some particular member. It has to build character, to develop individuality, to clear the human mind of spooks and shadows. It has to call men and women "out from the dark refinement, out from behind the screen, out from traditions and prejudices - into the open road."

St. Louis. Some people seem to be incapable of learning that Anarchism and dirty halls in squalid sections of the city are not synonymous. True, Anarchism does not exclude the poor, the dirty or the tramp any more than the sun excludes them, but it does not make a virtue of filth. It seems to me that so long as people remain satisfied with their present conditions, absolutely indifferent to cleanliness, air and beauty, they cannot possibly feel the burning shame of their lives, nor will they strive for anything that might lift them out of the ugliness of their existence. I do not censor anyone, for I am convinced that the boys of St. Louis tried their best ; yet I am grieved that they should be satisfied with so little. True, the halls were cheap, but through the future of Mother Earth depends upon the success of this tour, I cannot even for her sake speak in dingy little halls, dark and gloomy, with the dust and smoke making it impossible to breathe.

Minneapolis. Those who believe that only organizations or groups can accomplish things should profit by the example of Minneapolis, where two energetic workers did wonders.

The population of this city is composed of shopkeepers, bankers, doctors and lawyers - not the element that is usually interested in radical ideas. Nor were such ideas ever put before them. Anarchism was a spook, an evil spirit in that town, but daring is the only way to success. The audiences that thronged the halls for three successive evenings far surpassed in number and intelligence the most optimistic expectations. When I looked into the earnest faces, I felt that here were people who did not come to see but to hear, to be enlightened and to learn, and I was grateful to my good star, or rather the energy and perseverance of the two comrades who made such meetings possible.

The world is full of freaks - the Minneapolis Spook Club can certainly boast a large following. This organization is composed of professional men only, and they are known for their purity and morality, they never suffered the evil spirit of woman to invade their sanctum before. But thanks to the generosity of a friend, the rigid rules of the Spook Club were temporarily set aside. Possibly the members thought that one could not be a woman and an Anarchist at the same time. The angelic chastity of the Spookers would have been quite discomforting to me, were it not for the presence of a few daughters of that arch seducer Eve, who helped to bring some wit and humor into the dead atmosphere of statute and dissecting room wisdom. Specialists were there a-plenty, doctors enough to create any amount of disease, lawyers and a real live judge to induce one to commit crime, bump interpreters and bump producers, and so forth ; all important and awe inspiring gentlemen, but as innocent of the great questions of the day as new born bobs , their heads full of spooks and fears of all that their lack of wisdom could not grasp.

Winnipeg. The dirty crows - as a certain French artist named the priests - who infest the streets and cars of Montreal are not as numerous in Winnipeg, but the horrors of their creed are as dominant here as there - the creed that has for centuries gone about killing, burning and torturing is still holding the Canadian people in power, befogging their minds as in ages past.

The city was white on my arrival ; everything in the tight clutches of grim winter ; apparently not a sign of life or warmth. But the greetings of my comrades and the enthusiasm of the audiences soon convinced me that all was not cold or dead. Spring, the great awakener of life and growth, was stirring in the hearts of those who had come to hear me.

Men and women from every nook in the world gather at Winnipeg, the land of promise. They are soon made to realize, however, that the causes which drove them from their native shores - oppression, greed and robbery - are quite at home in this new, white land. The true great promise lies in all these nations coming together, to look one another in the face, to learn for the first time the real force that makes for wealth. Men and women knowing one another and clasping hands for one common purpose, human brotherhood and solidarity. Yes, Winipeg is the place of promise. It is the fertile soil of growth, life and ideas.

The Radical Club, but two years old, has become a tremendous factor in creating interest in new thought. My six days' visit seemed a dream. Large, eager audiences every evening and twice on Sunday, a beautiful social gathering that united two hundred men, women and children in one family of comrades, and people constantly coming and going during the day, all anxious to learn, made the time pass like a flash. When I stood on the platform of the train bidding a last farewell to a large group of friends, I keenly felt the pains of parting ; but this, too, I felt:

Allons! We must not stop here -

However sweet these laid-up stores, however convenient

this dwelling we cannot remain here,

However shelter'd this port and however calm these

waters, we must not anchor here,

However welcome the hospitality that surrounds us we

are permitted to receive it but a little while."

I wanted to be alone with my thoughts, alone with my impressions of those who had passed before me in long processions during my stay in Winnipeg. However, the official zeal of the Immigration Inspectors willed it differently. With the usual impudence that goes with authority I was subjected to the "third degree" : my name, occupation, whether American citizen, how long in America, and whether I had been out of the States before. Evidently the uniformed gentlemen had studied that infamous anti-Anarchist Immigration Law that will not admit "disbelievers in organized government." I assured my anxious protector that he would have to let me return, since I had been in America eighteen yeas before that stupid law was passed. Though myself a citizen of the world, my father happened to be privileged enough to become a citizen of this free country. After a long conversation with some others of his ilk, my good friend decided to let me go on. I know from experience that our law makers can do anything they please ; still, I venture to keep me out of this "sweet land of liberty." Besides, what are laws for if not to be evaded? No wonder so many "disbelievers in organized government" have flocked to American since the law against them became operative.

Poor, stupid Immigration Inspector! If you could have foreseen the result of your zeal, you might not have made it so public that the dangerous Emma Goldman was on the train. You got my fellow passengers intensely interested, with the result that I added a seventh meeting to those held at Winnipeg and disposed of a large number of magazines and pamphlets - not in the hall but in the Pullman sleeper. When will our fool governors learn that the best government is the one that governs least or not at all? Never before have I felt as convinced of this truth as on this tour. The rigid laws against Anarchists, passed within the past four or five years, the shameful misrepresentation of Anarchism, and the persecution of its adherents have awakened the most intense interest in our ideas in this country.Still more striking is the tremendous change in the attitude of the press. The papers in Toledo, Toronto, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Minneapolis and Winnipeg, especially those of the last two cities, have been remarkable for their fairness and decency in reporting my meetings. Probably they have learned that yellow journal methods, sensational, vulgar, untruthful reports are no longer believed by the thinking readers of newspapers. I wish our Eastern journalists would learn the same lesson and follow the example of one of their colleagues, the editor of the Winnipeg Tribune, who has this to say:

"Emma Goldman has been accused of abusing freedom of speech in Winnipeg, and Anarchism has been denounced as a system that advocates murder. As a matter of fact, Emma Goldman indulged, while in Winnipeg, in no dangerous rant and made no statement that deserved more than moderate criticism of its wisdom or logic. Also, as a matter of fact, the man who claims that Anarchism teaches bomb-throwing and violence doesn't know what he is talking about. Anarchism is an ideal doctrine that is now, and always will be, utterly impracticable. Some of the gentles and most gifted men of the world believe in it. The fact alone that Tolstoi is an Anarchist is conclusive proof that it teaches no violence.

"We all have a right to laugh at Anarchy as a wild dream. We all have a right to agree or disagree with the teachings of Emma Goldman. But we should not make ourselves ridiculous by criticising a lecturer for the things that she did not say, nor by denouncing as a violent and bloody a doctrine that preaches the opposite of violence."

(To be continued.)

* * *

SOCIALISM AND FATALISM

By H. Kelly.

THE relation between the two theories, roughly defined as Socialism and Fatalism, respectively, is more real than apparent. By Socialism I mean the Marxian brand, known in Europe as Social Democracy : the collective ownership of the land, means of production, distribution and exchange, controlled and regulated by a democratic State. Fatalism - the doctrine of inevitability : what is, had to be ; what was, will be. Leaving out of the question the law of gravitation, change of seasons and other natural phenomena, and applying the inevitability theory to individuals, fatalism is neither more nor less than a state of mind, resulting from repeated suggestion and repetition.

To illustrate. A fortune teller, after her palm has been crossed by a (the inevitable) piece of silver, solemnly informs a young lady of impressionable years that she will be married twice. The girl repeats the suggestion to herself and her friends throughout a number of years, until she finally becomes convinced that she must get married twice - and she does. Ergo, the fortune teller is vindicated.

Social Democrats have repeated the half-truth that man is the creature of circumstance and environment so often, that in the end their actions are moulded to fit their theory: they lose all individuality and initiative, becoming mere creatures of the ideas they have mouthed, without will or desire to act differently from the people they despise and look upon with contempt.

It has long been recognized by advanced thinkers that different races and different countries will work out their salvation in their own particular way and time. Anarchism and Socialism are theories applicable to the whole human race, but it is more than probably that certain countries will attempt the practical application of the new ideas before others and, necessarily, with certain modifications. If we compare France with Turkey, England with Persia, America with India, we appreciate the fact that things do not work out the same in all countries and with all races. Capitalism is common to them all, yet how differently it manifests itself in the development of the various countries.

Social Democracy, as taught by Marx and Engels, was expected to develop along similar lines in all countries. In fact, we have witnessed in recent years the spectacle, still extant, of the Social Democrats of Russia advocating a system whereby the peasants were to be deprived of their land and driven into the cities ; because, forsooth, in order to reach Socialism it is necessary to go through a period of industrialism of the kind we have in England and America. It is for this reason that Social Democrats have failed so signally to make converts among the peasants, while the Socialist Revolutionists, who advocated the retention of the land by the peasants, succeeded so well with the latter. All doubt on this point will be dissipated by consulting the current Russian revolutionary periodicals.

Collectivism was supposed to mean the same thing all over the globe ; yet time has proven the contrary.

European Socialists have rather a poor opinion of, amounting in some cases to positive contempt for, the intellectual ability of their American comrades. They will not be surprised to hear that we are evolving a set of Socialists here who, though worshiping Marx, hold ideas positively ludicrous in their heterodoxy to his gospel, as set forth in the Communist Manifesto. Heterodoxy is sometimes as foolish as orthodoxy. Some Socialists say that there is no reason why millionaires should not exist under Socialism ; others claim that even titles - purely for merit, or course - my be bestowed under that "Democratic Republic." In amazement we rub our eyes and wonder if the Collectivist ship has not slipped her moorings and the old religion lost its hold on its disciples. Wages will exist under Collectivism, we are told, and if a Melba refuses to sing unless we pay her ten or twenty times the amount that ordinary mortals receive, we will comply ; for as Mr. Wilshire says, we can't make her sing, and to put her on a bread and water diet is both impracticable and inhuman. There will always be, he says, lovers of a beautiful voice who will be willing to give this gentle rebel a portion of their remuneration in order to enjoy her golden notes. It's true, she will not be allowed to invest these "hours of labor" in any land or enterprise where unearned increment or exploitation is possible, but she can spend them in marble palaces, steam yachts or hogsheads of champagne. Leaving the solution of this "new Socialism" to others more apt at solving puzzles than myself, I will now pass on to the tactics advocated and practiced by American Socialists.

Inspired with the belief that capital is concentrating so rapidly that we shall soon have a great financial panic - with millions of men out of work and, therefore, lacking food, which condition will result in a Social Revolution - Mr. Gaylord Wilshire floats a gold mining company with shares valued at twenty-five million dollars, and uses the pages of a Socialist publication, Wilshire's Magazine, to sell the stock. Mr. Wilshire's efforts on behalf of Socialism have been in the past sincere, if undistinguished ; there is no reason why we should doubt his honesty of purpose now. His intention, we are informed, is to make a fortune and use it to help on the revolution. Quite as laudable and more respectable - he is nothing if not respectable - than those Anarchists who used to advocate stealing for the propaganda and ended by stealing for themselves. Of course, if this mine succeeds (Mr. Wilshire estimates that there is over three billion dollars worth of ore there), it will make all the shareholders rich and increase the number of the middle class by some scores of thousands. With righteous indignation against any "comrade" who openly seeks to defy and upset the law of gravitation (concentration of capital and abolition of the middle class) and jeopardize the honor of the movement, the National Executive of the party, who are proletarian lawyers, editors and so forth, are moved to protest. The situation is peculiar. If the mine is a failure, poor comrades lose their money ; if a success, they become middle-class exploiters. It is but natural that the most vigorous protestant against Mr. Wilshire is Mr. Hillquit, the "historian" of the party. The latter has been in the censuring business aforetime - only, on a never to be forgotten occasion, he was the censured - and it is quite natural he should be indignant over any violation of party ethics. In the language of his campaign literature, Mr. Hillquit is "a rising young lawyer" ; he is firmly grounded in Marxian fatalism and is reputed in some quarters to be worth no less than one hundred thousand dollars of unconcentrated capital. Far be it from me to suggest that the filthy lucre accumulated by this thrifty young man is invested in tenement houses or factories á la Frederick Engels ; or that he is drawing a beggarly four percent from a savings bank. It is, to use a colloquialism, a "cinch" that his money is buried in some sub-cellar where its contaminating influence is safely quarantined from the "comrades" and the "movement."

The campaign waged by Mr. Hillquit last fall, as Congressional candidate from the ninth district, was undoubtedly the last word in political opportunism; the most charitable person, if free from party prejudice, can have nothing but contempt for methods which differed in no particular from a rotten Tammany or a debauched Republican party. If this gentleman enjoys but one-forth of the income he is credited with, he receives considerably more from his law practice than he would as Congressman ; as is the case of Mr. Wilshire, we may absolve him from any desire to profit financially by going to Congress. (In passing we may add that the mileage graft and other extras paid Congressmen are so great that on a salary of five thousand dollars per year a certain Congressman from my State, Missouri, had saved eleven thousand dollars in two years, besides paying all his expenses. Congressional salaries have recently been increased to seven thousand five hundred dollars a year.) While not doubting Mr. Hillquit's honesty, we are not clear as to the principles he holds in trying to ride into office by the methods he pursued.

For a generation the workers have been told that a vote for a Socialist candidate is a vote for Socialism ; how pale and sickly that sounds in the light of the campaign we have been speaking of. The voters of the ninth Congressional district were urged to vote for the party candidate on the grounds that "Mr. Hillquit is a rising young lawyer and a Russian Jew ; he will look after the interests of the Jews in Russia ; be the spokesman for the Russian revolution ; the workers of the ninth district are among the poorest paid in the United States, living in the most overcrowded und unsanitary conditions" ; finally the voters were instructed how they could split the ticket, voting for Tammany or the Republican party and still electing the Socialist Congressional candidate. We have here an appeal to race prejudice and snobbishness, and the implication that a Socialist Congressman could increase wages, improve local sanitary conditions, and reduce overcrowding, when the veriest child at schools knows that Congress has nothing ever to do with such matters.

It may be said: "Yes, all that you say is true, but did not the party censure Mr. Hillquit?" Yes, after the election! Not a word of disapprobation was heard during the campaign, and it requires a mind singularly inexperienced in politics to conceive of any member of the Socialist party raising the question, had the party candidate been elected. The end would have justified the means ; an attack upon the honor or good faith of the first Socialist Congressman would have been considered high treason. In fact, it is doubtful if the question would have even arisen, had it not been for the instructions regarding the split ticket. This was the real crime ; the other incidents were trifles. The answer of a member of the Executive of the party to my protest against such dishonest tactics was that my objections were "petty, even childish, and they bored him."

When it is pointed out that every reform or revolutionary movement must, in order to have nay real or lasting success, have an ethical basis, and the morals of the party be judged by its meanest member, we are informed that it is a utopian doctrine long since exploded or that we do not understand Socialism ; further, that Socialism will come, not because it is just or demanded by the people, but because it is necessary. Socialists, such as those we have mentioned - they are typical, representing fairly accurately the party at large - have repeated so often that capitalist politics are rotten, and men's ethics, religion and every-day actions are governed and determined by the manner in which they obtain their livelihood, that they have arrived at the point where their actions conform to their theories. Socialism is inevitable, and man is the creature of circumstance and environment ; the fact that I, who advocate the abolition of exploitation and point out its evil effects, am myself an exploiter, does not affect the sum total of human happiness or misery, or the ultimate realization of Socialism. The individual counts for nothing ; Socialism is inevitable. Acting on this basis, our politics are as corrupt, proportionally, as our environment, and we exploit in the name of a principle. Truly a wonderful philosophy, this fatalistic Socialism which justifies everything from exploitation to the beating of one's wife, on the ground that "we are the creatures of our environment and victims of the present system." It is the proud boast of the advocates of Socialism that there are no less than thirty million Socialists in the world. Of course there are not, but if there were, and if each one of them considered himself an individual, conscious of his powers as well as of his limitations - a human entity of sufficiently intelligent to understand the necessity of a social change, as well as to realize the importance of the individual as a determining social factor ; if to this understanding were added a moral concept of exploitation, what a mighty revolution those thirty millions could accomplish!

* * *

FLASHES FROM THE FLINT

By Victor Robinson.

THE history of progress is written in one word: disobedience.

What is all this talk I hear about a Redeemer and a coming Messiah? The world has but one Savior, and his name is Freedom!

Authority is the dam which has blocked the river of civilization ; it is the clog in the wheel of improvement, the barnacle on the ship of science, the dark cloud which obscures the dawn of day.

Where God is king, the people are devils.

The reformer in prison is more free than the conservative who imprisoned him, for the chains of superstition in a man's mind are more cruel than the fetters of iron on the convict's ankles.

* * *

STIRNER: "THE EGO AND HIS OWN"

By Max Baginski.

I.

Benjamin R. Tucker has published the first English translation of "Der Einzige und sein Eigentum," written in 1845 by the ingenuous German thinker Kaspar Schmidt under the pseudonym of Max Stirner. The book has been translated by Steven T. Byington, assisted by Emma Heller Schumm and George Schumm. Mr. Tucker, however, informs us in his Preface to the book that "the responsibility for special errors and imperfections" properly rests on his shoulders. He is therefore also responsible for the Introduction by the late Dr. J. L. Walker, whose narrow-minded conception of Stirner is suggestive of Individualistic idolatry.

Stirner said: "Ich hab' mein' Sach' auf Nichts gestellt." ("I have set my cause on naught.")1 It seems that the Individualist Anarchists have set their cause on Stirner. Already they have sent money to Bayreuth and Berlin, for the purpose of having the customary memorial tables nailed to the places of Stirner's birth and death. Like the devout pilgrims wending their way Bayreuth-wards, lost in awed admiration of the musical genius of Richard Wagner, so will the Stirner worshipers soon begin to infest Bayreuth and incidentally cause a raise in the hotel charges. The publishers of Baedeker will do well to take note of this prophecy, that the attention of the traveling mob be called to the Stirner shrines.

A harmless bourgeois cult. Involuntarily I am reminded of another theoretic Individualist Anarchist, P. J. Proudhon, who wrote after the Paris February Revolution : "Willy-nilly, we must now resign ourselves to be Philistines."

Possibly Dr. J. L. Walker had in mind such resignation when he contemptuously referred in his Introduction to Stirner's book to the "so-called revolutionary movement" of 1848. We regret that the learned doctor is dead; perhaps we could have successfully demonstrated to him that this revolution - in so far as it was aggressively active - proved of the greatest benefit to at least one country, sweeping away, as it did, most of the remnants of feudalism in Prussia. It were not their evolutionists who compromised the revolution and caused the reaction ; the responsibility for the latter rests rather on the champions of passive resistance, á la Tucker and Mackay.

Walker did not scruple to insinuate that Nietzsche had read Stirner and possibly stolen his ideas in order to bedeck himself with them ; he had omitted, however, to mention Stirner. Why? That the world might not discover the plagiarism. The disciple Walker proves himself not a little obsessed by the god-like attributes of his master, as he suspiciously exclaims: "Nietzsche cites scores or hundreds of authors. Had he read everything, and not read Stirner?"

Good psychologic reasons stamp this imputation as unworthy of credence.

Nietzsche is reflected in his works as the veriest fanatic of truthfulness with regard to himself. Sincerity and frankness are his passion - not in the sense of wishing to "justify" himself before others : he would have scorned that, as Stirner would - it is his inner tenderness and purity which imperatively impel him to be truthful with himself. With more justice than any of his literary contemporaries could Nietzsche say of himself : "Ich wohne in meinem eignen Haus," 2 and what reason had he to plagiarize? Was he in need of stolen ideas - he, whose very abundance of ideas proved fatal to him?

Add to this the fact that the further and higher Nietzsche went on his heroic road, the more alone he felt himself. Not alone like the misanthrope, but as one who, overflowing with wealth, would vain make wonderful gifts, but finds no ears to hear, no hands capable to take.

How terribly he suffered through his mental isolation is evidenced by numerous places in his works. He searched the past and the present for harmonious accords, for ideas and sentiments congenial to his nature. How ardently he reveres Richard Wagner and how deep his grief to find their ways so far apart! In his latter works Nietzsche became the most uncompromising component of Schopenhaur's philosophy ; yet that did not prevent his paying sincere tribute to the thinker Schopenhaur, as when he exclaims: "Seht ihn euch an --

Niemandem war er untertan."3

Were Nietzsche acquainted with Stirner's book, he would have joyfully paid it - we may justly assume - the tribute of appreciative recognition, as he did in the case of Stendhal and Dostoyevsky, in whom he saw kindred spirits. Of the latter Nietzsche says that he had learned more psychology from him than from all the textbooks extant. That surely does not look like studied concealment of his literary sources.

In my estimation there is no great intellectual kinship between Stirner and KNietzsche. True, both are fighting for the liberation of individuality. Both proclaim the right of the individual to unlimited development, as against all "holiness," all sacrosanct pretensions of self-denial, all Christian and moral Puritanism ; yet how different is Nietzsche's Individualism from that of Stirner!

The Individualism of Stirner is fenced in. On the inside stalks the all-too-abstract I, who is like unto an individual as seen under X-rays. "Don't disturb my circle!" cries this I to the people outside the fence. It is a somewhat stilted I. Karl Marx parodied Stirner's Einzigkeit by saying that it first saw the light in the narrow little Berlin street, the Kupfergraben. That was malicious. In truth, however, it cannot be denied that Stirner's Individualism is not free from a certain stiffness and rigidity. The Individualism of Nietzsche, on the other hand, is an exulting slogan, a jubilant war-cry ; more, it joyfully embraces humanity and the whole world, absorbs them, and, thus enriched, in turn penetrates life with elementary force.

But why contrast these two great personalities? Let us rather repeat with M. Messer - who wrote an essay on Stirner - Goethe's saying with regard to himself and Schiller: "Seid froh, dass ihr solche zwei Kerle habt."4

That the champions of pure-and-simple Individualism can be as captious and petty towards other individualities as the average moralist is proven by the extremely tactless remark in Tucker's Preface about Stirner's swetheard, Marie Daehnhard. Stirner dedicated his book to her ; for that he must now be censored by Mackay-Tucker in the following manner:

Mackay's investigations have brought to light the Marie Daehnhardt had nothing whatever in common with Stirner, and so was unworthy of the honor conferred upon her. She was no Eigene. I therefore reproduce the dedication merely in the interest of historical accuracy."

No doubt Tucker is firmly convinced that Individualism and Einzigkeit are synonymous with Tuckerism. FOrtunately, it's a mistake.

Max Stirner and Marie Daehnhardt surely knew better what they had in common at the time of the dedication than Tucker-Mackay knows now.

But we must not take the matter too seriously. Stirner belongs to those whom even their admirers and literary executors cannot kill off. Mr. Traubel and the Conservator have not as yet succeeded in disgusting me with Walt Whitman ; neither can the Individualists Anarchists succeed in robbing me of Stirner.

A great fault of the translation is the failure to describe the contemporary intellectual atmosphere of Germany in Stirner's time. The American reader is left in total ignorance as to the conditions and personalities against which the ideas of Stirner were directed. This is, moreover, dishonest - undesignedly so, no doubt - with regard to the Communists. Stirner's controversy was specifically with Wilhelm Weitling - who, by the way, is probably quite unknown to most American readers ; it were therefore no more than common honesty to state that the Communism of Weitling bears but a mere external resemblance to modern Communism as expounded, among others, by Kropotkin and Reclus. Modern Communism has ceased to be a mere invention, to be forced upon society ; it is rather a Weltanschauung founded on biology, psychology and economy.

The English edition of "The Ego and his Own" impresses one with the fact that the translator spared no pains to give an adequate and complete work ; unfortunately, he has not quite succeeded. It is a case of too much philogy and too liter intuitive perception. Stirner himself is partly responsible for this, because in spite of his rebellion against all spooks, he is past master in playing with abstractions.

II.

Stirner's "Der Einzige und sein Eigentum" was a revolutionary deed. It is the rebellion of the individual against those "sacred principles" in the name of which he was ever oppressed and subjected. Stirner exposes, so to say, the metaphysics of tyrannical forces. Luter nailed his ninety-five accusations against Popery to the door of the Schlosskirche at Wittenberg ; Stirner's declaration of independence of the individual throws down the challenge to ALL things "sacred" - in morals, family and State. He tears off the mask of our "inviolable institutions" and discovers behind them nothing but - spooks. GOD, SPIRIT, IDEAS, TRUTH, HUMANITY, PATRIOTISM - all these are to Stirner mere masks, behind which - as from the holy mountain - issue commands, the Kantian categoric imperatives, all signed to suppress the individuality, to train and drill it and thus to rob it of all initiative, independence and Eigenheit All these things claim to be good in themselves, to be cultivated for their own sake and all exact respect and subjection, all demand admiration, worship and the humiliation of the individual.

Against all this is directed the rebellion of the I with its Eigenheit and Einzigkeit. It withholds respect and obedience. It shakes from its feet the dust of "eternal truths" and proclaims the emancipation of the individual from the mastery of ideals and ideas; henceforth the free, self-owning Ego must master them. He is no more awed by the "good" ; neither does he condemn the "bad." He is sans religion, sans morals, sans State. The conception of Justice, Right, General Good are no more binding upon him ; at the most , he uses them for his own ends

To Stirner, the Ego is the centre of the world ; wherever it looks, it finds the world its own - to the extent of its power. If this Ego could appropriate the entire world, it would thereby establish its right to it. It would be the universal monopolist. Stirner does not say that he wants his liberty to be limited by the equal liberty of others ; on the contrary, he believes that his freedom and Eigenheit are bounded only by his power to attain. If Napoleon uses humanity as a football, why don't they rebel?

The liberty demanded by his democratic and liberal contemporaries was to Stirner as mere alms thrown to a beggar.

J. L. Walker entirely misunderstands the very spirit of Stirner when he states in his Introduction : "In Stirner we have the philosophical foundation for political liberty." Stirner has nothing but contempt for political liberty. He regards it in the light of a doubtful favor that the powerful grant to the powerless. He, as Eigener would scorn to accept political liberty if he could have it for the asking. He scoffs at those who ask for human right and beg liberty and independence, instead of taking what belongs to them by virtue of their power.

It is this very criticism of political liberty that constitutes one of the most ingenuous parts of Stirner's book. This is best proven by the following quotation:5

"'Political liberty,' what are we to understand by that? Perhaps the individual's independence of the State and its laws? No ; on the contrary, the individual's subjection in the State and to the State laws. But why 'liberty'? Because one is no longer separated from the State by intermediaries, but stands in direct and immediate relation to it ; because one is a - citizen, not the subject of another, not even of the king as a person, but only in his quality as 'supreme head of the State.' . . .

"Political liberty means that the polis, the State, is free ; freedom of religion that religion is free, as freedom of conscience signifies that conscience is free ; not, therefore, that I am free from the State, from religion, from conscience, or that I am rid of them. It does not mean my liberty , but the liberty of a power that rules and subjugates me ; it means that one of my despots, like State, religion, conscience, is free. State, religion, conscience, these despots, make me a slave."

Stirner is anti-democratic as well as anti-moral He did not believe that the individual would be freed from his moral fetters by "humanizing the diety," as advocated by Ludwig Feuerbach ; that were but to substitute moral despotism for religious. The divine had grown senile and enervated ; something more virile was required to further keep man in subjection.

By embodying the "God idea" in man, the moral commands are transformed into his very mental essence, thus enslaving him to his own mind instead of to something external ; thus would the former merely external slavery be supplanted by an inner thraldom through his ethical fear of being immoral. We could rebel against a mere external God ; the moral, however, becoming synonymous with the human, is thus made ineradicable. Man's dependence and servitude reach in this humanizing of the divine their highest triumph - freed from the thraldom of an external force he is now the more intensely the slave of his own "inner moral necessity."

Every good Christian carries God in his heart; every god moralist and Puritan , his moral gendarme.

The freethinkers have abolished the personal God and then absorbed the ethical microbe, thus inoculating themselves with moral scrofula. They proudly proclaimed their ability to be moral without divine help, never suspecting that it is this very morality that forges the chains of man's subjugation. The rulers would cheerfully ignore the belief in God if convinced that moral commands would suffice to perpetuate man in his bondage. While the "hell of a sick conscience" is in yourself - in your bones and blood - your slavery is guaranteed.

In this connection Stirner says :

"Where could one look without meeting victims of self-renunciation? There sits a girl opposite me, who perhaps has been making bloody sacrifices to her soul for ten years already. Over the buxom form droops a deathly-tired head, and pale cheeks betray the slow bleeding away of her youth. Poor child, how often the passions may have beaten at your heart, and the rich powers of youth have demanded their right! When your head rolled in the soft pillow, how awakening nature quivered through your limbs, the blood swelled your veins, and fiery fancies poured the gleam of voluptuousness into your eyes! Then appeared the ghost of the soul and its external bliss. You were terrified, your hands folded themselves, your tormented eye turned its look upward, you - prayed. The storms of nature were hushed, a calm glided over the ocean of your appetites. Slowly the weary eyelids sank over the life extinguished under them, the tension crept out unperceived from the rounded limbs, the boisterous waves dried up in the heart, the folded hands themselves rested a powerless weight on the unresisting bosom, one last faint "Oh dear!" monaed itself away, and - the soul was at rest. You fell asleep, to awake in the morning to a new combat and a new - prayer. Now the habit of renunciation cools the heat of your desire, and the roses of your youth are growing pale in the chlorosis of your heavenliness. The soul is saved, the body may perish! O Lais, O Ninon! how well you did to scorn this pale virtue! One free grisette against a thousand virgins grown gray in virtue!"

The the chains fall one by one from the sovereign I. It rises ever higher above all "sacred commands" which have woven his strait-jacket.

That is the great liberating deed of Stirner.

Abstractly considered, the Ego is now einzig ; but how about his Eigentum?6 We have now reached the point in Stirner's philosophy where mere abstractions do not suffice.

The resolving of society into einzige individuals leads, economically considered, to negation. Stirner's life is itself the best proof of the powerlessness of the individual forced to carry on a solitary battle in opposition to existing conditions.

Stirner demolishes all spooks ; yet, forced by material need to contract debts which he cannot pay, the power of the "spooks" proves greater than that of his Eigenheit : his creditors send him to prison. Stirner himself declares free competition to be a mere gamble, which can only emphasize the artificial superiority of toadies and time-servers over the less proficient. But he is also opposed to Communism which, in his opinion, would make ragamuffins of us all, by depriving the individual of his property.

This objection, however, does not apply to a very large number of individuals, who do not possess property anyhow ; they become ragamuffins because they are continually compelled to battle for property and existence, thus sacrificing their Eigenheit and Einzigkeit.

Why were the lives of most of our poets, thinkers, artists and inventors a martyrdom? Because their in individualities were so eigen and einzig that they could not successfully compete in the low struggle for property and existence. In that struggle they had to market their individuality to secure means of livelihood. What is the cause of our corruption of character and our hypocritical suppression of convictions? It is because the individual does not own himself, and is not permitted to be his true self. He has become a mere market commodity, an instrument for the accumulation of property - for others.

What business has an individual, a Stinerian, an Eigener in a newspaper office, for instance, where intellectual power and ability are prostituted for the enrichment of the publisher and shareholders. Individuality is stretched on the Procrustes of bed of business ; in the attempt to secure his livelihood - very often in the most uncongenial manner - he sacrifices his Eigenheit, thus suffering the loss of the very thing he prizes most highly and enjoys the best.

If our individuality were to be made the price of breathing, what ado there would be about the violence done to personality! And yet our very right to food, drink and shelter is only too often conditioned upon our loss of individuality. These things are granted to the propertyless millions (and how scantily!) only in exchange for their individuality - they become the mere instruments of industry.

Stirner loftily ignores the fact that property is the enemy of individuality , - that the degree of success in the competitive struggle is proportionate to the measure in which we disown and turn traitors to our individuality. We may possibly except only those who are rich by inheritance ; such persons can, to a certain degree, live in their own way. But that by no means expresses the power, the Eigenheit of the heir's individuality. The privilege of inheriting may, indeed, belong to the veriest numskull full of prejudice and spooks, as well as to the Eigener. This leads to petty bourgeois and parvenu Individualism which narrows rather than broadens the horizon of the Eigener.

Modern Communists are more individualistic than Stirner. To them, not merely religion, morality, family and State are spooks, but property also is no more than a spook, in whose name the individual is enslaved - and how enslaved! The individuality is nowadays held in far stronger bondage by property, than by the combined power of State, religion and morality.

Modern Communists do not say that the individual should do this or that in the name of Society. They say : "The liberty and Eigenheit of the individual demand that economic conditions - production and distribution of the means of existence - should be organized thus and thus for his sake." Hence follows that organization in the obedience or despotism. The prime condition is that the individual should not be forced to humiliate and lower himself for the sake of property and subsistence. Communism thus creates a basis for the liberty and Eigenheit of the individual. I am a Communist because I am an Individualist.

Fully as heartily the Communists concur with Stirner when he puts the word take in place of demand - that leads to the dissolution of property, to expropriation.

Individualism and Communism go hand in hand.

- Erroneously translated by Byington: "All things are nothing to me." Return

- Literally, "I live in my own house." Return

- "Observe him - he is mastered by no one." Return

- "Rejoice that you have two such capital fellows." Return

- We quote Byington's version.Return

- Meaning, in this connection, property. Return

* * *

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN.

A discreet intimation to all those whose subscription has long since expired. We hate to leave an old friend behind. If you feel likewise, send in your dollar.

* * *

L I B E R T Y

By A. T. Heist.

WHEN I speak to my "intelligent" friends about the beauty of individual independence and personal liberty, I am informed that we are all dependent both upon nature and one another, and that, therefore, there can be no such thing as human independence or human liberty. Such stupid ones are confounding absolute freedom with civil or social liberty, and think that by disbelieving the existence of the former they are denying the possibility of the latter.

Many who esteem themselves to be "radical" libertarians also seem to me to have blurred notions about the nature and limitations of liberty. For this reason I write, hoping that by so doing I will clarify my own vision a little, and that of some readers a great deal.

It may be just as well to being by stating some matters that are not involved in my idea of liberty. It seems to me that no scientific conception of human freedom can imply the idea of freedom from the operation of natural law, either in the physical world or in the social organism. Neither can it involved the assumption of the lawlessness of human volition, for be it remembered that most people still cling to the old "free will" superstition. I say, then, that every rational conception of human freedom must be grounded upon the demonstrated fact that each of us, even in the realm of the intellect, is always subject to the uniformity and universality of the reign of natural law.

Liberty under subjection to universal natural law only means that every person shall be permitted to find his own happiness in his own most perfect adjustment to the conditions of his own well being, under the natural law of the social organism, operating without interruption or interference from any artificial state-made or other abnormal conditions, such as actually subvert the normal operations of natural law. In this last clause I have in mind the intervention of mental disease, through which unhealthy condition there might be produced such effects as are an invasive subversion of the natural law of the social organism.

May be this generalization is too abstruse for some. In the fear of this I shall endeavor to make it more plain and particular by re-stating the formula as applied separately to physical liberty, intellectual liberty and civil liberty.

When I appply my formula about liberty to the bodily life of man, I come to this conclusion : physical liberty for the human infant means the universal admission of its claim to develop an unmutilated and undeformed full maturity. From this it follows that parents are guilty of invasive conduct towards their child, whenever they contribute, even though unconsciously and remotely, toward their offspring's failure to reach the full stature of an unmutilated and undeformed manhood.

For the healthy adult physical liberty means the exercise of all his faculties in freedom from all artificial, man-made restraints, and so long as the indulgence of his capacities does not in itself constitute an unwelcome, artificial restraint or invasion upon another.

But here I come again to the difficult task of stating what I mean by artificial restraints, since, in the broadest sense, even limitations of human contrivance are a part of nature. By artificial restraints I mean those restraints of human contrivance which find the necessity for their existence solely in the special attitude of mind of those individuals who restrain or invade, and which restrictions would be avoidable, because unnecessary, except for that special psychologic necessity.

For the infant, intellectual liberty under natural law must mean the universal admission of his claim to be instructed in the laws of nature, under which term I include not only things and their forces, but men and their ways, and the fashioning of the affections and of the will into an earnest and loving desire to live inharmony with those laws.