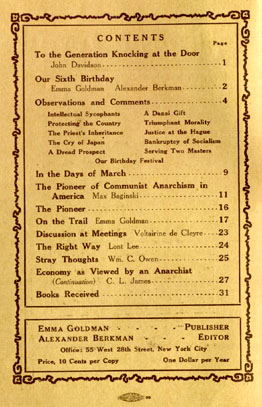

Click the title of the desired article

| Vol. VI |

MARCH, 1911 |

No. 1 |

By JOHN DAVIDSON.

Break-break it open; let the knocker rust;

Consider no "Shalt not," nor no man's "must";

And, being entered, promptly take the lead,

Setting aside tradition, custom, creed;

Nor watch the balance of the huckster's beam;

Declare your hardiest thought, your proudest dream;

Await no summons; laugh at all rebuff;

High hearts and you are destiny enough.

The mystery and the power enshrined in you

Are old as time and as the moment new;

And none but you can tell what part you play,

Nor can you tell until you make essay,

For this alone, this always, will succeed,

The miracle and magic of the deed.

WITH this issue Mother Earth begins her sixth journey through life.

Five years! What an infinitesimal drop in the ocean of eternity; yet how terribly long a time when travelled on a hard, thorny road. With a world of ignorance and prejudice to battle against, a thousand obstacles to overcome, hosts of enemies to face, and with but few friends, MOTHER EARTH has withstood, for five years, the storm and stress of the firing line, and has wavered not.

More than once was she stabbed by the enemy, and hurt by the thrusts of the well-meaning; more than once was her body bruised, her flesh torn by conflicting forces; yet never has she fallen by the wayside, nor her ardor been subdued.

Now that Mother Earth begins her sixth journey, it behooves us to halt a moment and to ponder the question: Was the struggle and pain worth while? has the magazine justified the expectations that gave it life?

Not long ago a f friend wrote to us: Why don't you give up? Why waste your time and energy in a lost cause? Mother Earth has not reached the people you had hoped to reach, nor does the magazine satisfy even some of our own comrades, because-as they say-more reading matter than is contained in MOTHER EARTH can be had in the ordinary magazines, for ten cents.

Viewed from the dominant standpoint of success, our friend is right. In that sese Mother Earth has failed. Our circulation is still far from the fifty-thousand mark; our subscribers, too, do not represent the multitudes. Nor is our financial rating such that we need feel any anxiety lest a Wall Street panic break our bank. Again, Mother Earth has lost in averdupois; it began as a heavyweight of sixty-four pages, but is now reduced to the lightweight class.

But since when do Anarchists measure success by quantity? Are numbers, weight, or following the true criterion of success? Should not the latter consist, first of all, in adherence to the chosen purpose, no matter at what cost? Indeed, the only success of any value has been the failure of men and women who struggled, suffered, and bled for an ideal, rather than give up, or be silenced.

Mother EARTH is such a success. Without a party to back her, with little or no support from her own ranks, and consistently refusing to be gagged by a profitable advertising department, she has bravely weathered the strain of five years, stormy enough to have broken many a strong spirit. She has created an atmosphere for herself which few Anarchist publications in America have been able to equal. She has gathered around her a coterie of men and women who are among the best in the country, and, finally, she has acted as a leaven of thought in quarters least expected by those who are ready with advice, yet unable to help.

Many an editor of our better-class dailies has found in MOTHER EARTH a source of information and inspira- and though they would be loth to admit it, it is nevertheless true that they have used our magazine for copy on numerous occasions. That, among other things, may help to account for the decided change in the tone of the press towards Anarchism and Anarchists.

But for want of space many instances could be cited, showing how well and widely MOTHER EARTH is read by journalists and writers, and what is thought of her merits by those who value quality above quantity.

As to the original raison d'etre of MOTHER EARTH, it was, first of all, to create a medium for the free expres on of our ideas, a medium bold, defiant, and unafraid. That she has proved to the fullest, for neither friend nor foe has been able to gag her.

Secondly, MOTHER EARTH was to serve as a gathering point, as it were, for those, who, struggling to free themselves from the absurdities of the Old, had not yet reached firm footing Suspended between heaven and hell, they have found in MOTHER EARTH the anchor of life.

Thirdly, to infuse new blood into Anarchism, which-in America-had then been running at low ebb for quite some time.

All these purposes, it may be said impartially, the magazine has served faithfully and well.

We cannot claim for MOTHER EARTH hosts of followers, but she has made some friends whose steadfast devotion and generosity has accomplished greater results than would have been possible with a large income. Besides, our magazine would have long ere this been selfsupporting, were it not for the many other issues drawing upon its resources.

We have created an American Anarchist propaganda literature, which has consumed the largest part of the magazine's income; indeed, it is this, more than anything else, which has been such a drain on our funds.

On the whole, we feel that our fighter has more than justified its existence. True, MOTHER EARTH is far from perfect; but, after all, it is the striving for, rather than the attainment of, perfection which is the essence of all effort, of life itself.

The struggle is ever before us. With increased determination and greater enthusiasm MOTHER EARTH enters upon the sixth year, confident that her friends need no other assurance than that the magazine will continue on the great Open Road, with face ever turned toward the Dawn.

EMMA GOLDMAN,

ALEXANDER BERKMAN.

TWO intellectuals-American exchange Professors Munsterberg and Smith-recently fell upon each other regarding the question which of them had the better right to be invited to the annual exhibition of naked busts and shoulders at the Berlin court.

Professor Smith claimed priority because the Kaiser had conversed with him thirteen minutes longer than with his learned colleague. Smith asserted that His Majesty even deigned to grin at him once. But Professor Munsterberg angrily retorted that though it was true that the Kaiser had talked with him only a couple of minutes, the royal manner was so gracious as to entirely discount the thirteen minutes of Smith. The matter threatened to cause international complications, when it was finally settled by inviting both sycophants to the court ball.

A couple of country schoolmasters from Darkest Pomerania could not have demeaned themselves worse than these representatives of American science. Of such professional intellectuals Schopenhauer was wont to say, "They don't live for, but off, science." There is another well-known adage which fitly characterizes such worthies: Professors and prostitutes are for sale.

THE people of the United States are to be blessed by President Taft with an extra session of Con gress. Is it for the purpose of "filling the empty mar ket basket," as the phrase runs? Far from it. The special Danai gift has the sole purpose of obscuring, by superficial legal phraseology, the real causes of the empty market basket. Expropriation of the monopo- lords of land and industry by the dear, victimized patriots is the best and only way to terminate the usury in the necessaries of life. This, it's dead sure, will never be decided by Congress.

THERE are strong indications that Washington is mobilizing troops against the revolution in Mexico, to protect the property interests of the Morgans, Gugenheims, Hearsts, et al. A beautiful prospect for the American soldier, to be maimed or killed for the sake of protecting the dividends of the multi-millionaires, and then be persuaded that he had helped to enhance the honor and glory of his country. It is high time that anti-militarist arguments begin to be studied in America.

THE greatest triumph of the reigning morality manifestly consists in trials for breach of promise. It seems hardly possible for our merchant order of buy and selling to go much further than counting romance, affection, kisses, and embraces in dollars and cents.

All poets of love songs, dead or living, should be indicted and brought before the American courts. It would be easy to prove against them that they have aroused, a thousandfold, sweet yearnings, emotions, and tender hopes in female hearts, without giving further satisfaction. Surely these sinners should be punished.

To simplify matters, love and proofs of love, genuine or counterfeit, could be sold at auction. For instance: Here, gentlemen, your kind attention, please! Here's a well-preserved daughter of an American millionaire- a European Count-now divorced. What 'm I offered? Five dollars, first bid! Five, ten, twenty. . .

0NE of the fashionable preachers of New York, Dr. Aked, of the Rockefeller Church, threatens to leave his flock to go to the Pacific Coast, where a more remunerative position has been offered to him.

Yes, the priests have inherited from the apostles only the purse and the Judas kiss.  OUR readers no doubt remember the case of Savakar, the Hindu revolutionist, referred to in a previous issue Of MOTHER EARTH.

The English courts sentenced Savakar to be transported to India and to be imprisoned there. On the way the Hindu succeeded in jumping overboard, at Marseille, and swimming safely to land. According to international agreement, Savakar should have been safe, on French soil, from the bloodhounds of England. But French gendarmes arrested and returned him to the English ship, feeling sure that all means are justified toward revolutionists.

They were right. The International Peace Conference, at The Hague, to which the case was submitted, decided that it was lawful to hunt down Savakar on French soil and deliver him into the hands of the British hangman.

Surely the decision would have been quite different had Savakar been an absconded banker instead of a revolutionist.

CONDITIONS in Japan are steadily growing more unbearable. From reliable information we learn about the increased persecution of radicals, numerous arrests of persons suspected of "political untrustworthi- secret trials, and long imprisonments.

"The government of the little brown men,"-we quote one of our correspondents, a personal friend of the martyred Kotoku-"is mad with thirst for human blood. Katsura asserts that he will spare no one. Hundreds are daily dragged off to the prisons, and none is secure. . . . What can be done? What is the International Socialist Bureau doing? Where is its influence? Can't the various Socialist representatives and newspapers in the different countries be moved to interpellate? . . . Leave nothing undone and arouse the comrades everywhere to the true condition of affairs." Will the cry of awakening Japan be heard?

WHEN Socialism had not yet become so fatally in fected with the germ of political tuberculosis, it used to preach: The efforts of bourgeois reformists are misleading and useless, since they can work no es sential change in the economic conditions of society upon which are founded our political, moral, and social in stitutions. That is to say, that so long as private prop erty, wage slavery, and capitalism rule economically, no political reforms are worth while, because they cannot in the least alter the character of existing society.

But since their infection with the bacillus of this tuberculosis, the Socialists have been claiming: Give us majorities, political power, and we will accomplish wonderful economic reforms.

In Milwaukee the yearned-for ballot majority has really been achieved, with the result that the Social Democratic politicians now find themselves in the same position as the bourgeois reformists. They can make no vital changes, because their cherished "economic foundation" faces them at every turn.

Poor Mayor Seidel! His moral heart longs to abolish prostitution in Milwaukee, but-economic interests and the police will not permit it. He would transform the city into a second Eden, but-Milwaukee is so much In debt (like every large city under capitalist regime) that nothing can be done, He would this and he would that, but he succeeds only in giving a poor imitation of the bourgeois reformists, whom the Socialists have always so justly ridiculed. Thus the much-praised "polit- power of the ploretariat" proves itself, in capitalist practice, a hollow mockery.

One thing, however, has been achieved: a salary of seven thousand five hundred per annum for Victor Berger, the newly elected member of Congress. But it is doubtful whether the proletarian voters of Wisconsin will find sufficient consolation in this only "practical result."

THE discussion in the New York Call between Upton Sinclair and Dr. Robinson as to whether fasting is preferable to eating fills us with dread lest a considerable number of donkeys and freak Socialists commit suicide by voluntary starvation. It would be sad, indeed, but we shall try to bear up manfully at the burial ceremonies.

WITH rather poor grace John Mitchell has given up his sinecure in the Civic Federation, after the Convention of the Mine Workers had decided that no official of that veiled plutocratic conspiracy may be a member of the miners' organization.

Reason prompted to obey the resolution of the Convention; but the heart of Mitchell remains with the Civic Federation, as is shown by the letter he addressed to Seth Low. Thus only half the work has been done. Neither one holding an office with the Civic Federation, nor one who strives to impregnate the workers with the spirit of that capitalist organization properly belongs in the labor movement.

The Miners' Union would do well to present John Mitchell, for good and all, as an unconditional free gift to the Civic Federation, In truth, they could well afford, if necessary, to throw some money in with the bargain.

THE friends of MOTHER EARTH will celebrate the Sixth Birthday of our little fighter, Friday, March 17th, at Terrace Lyceum, 206 East Broadway, where speeches, song, music, and "the light, fantastic toe" will give the proper spirit to the occasion.

We regret that distance will probably make it impossible for our friends "in the country" to participate in the jollification. But we know that they will be with us in spirit, and we hope they will remember the five-year-old by return mail. A word to the wise is sufficient.

HISTORY relates that on March thirteenth, in the year 44 B. C., Julius Caesar fell a victim to the daggers of the conspirators who defended the old Roman liberties against the rising tide of imperialism. But, evidently, imperialism had not received on that occasion its death blow. After two thousand years it is still alive, and is-if certain prophets are rightabout to plant its banner upon the towers of this Republic. The struggle between Caesar and Brutus has not yet ceased.

It was in the Days of March, 1770, that the first blood of the martyrs of the Colonies was shed in Boston. Six years later the redcoats were ignominiously driven from that city.

In March, 1819, the German student, Karl Sand, killed the Russian spy Kotzebue. The month of March, in the year 1821, witnessed the beginning of the Greek struggle for independence, and in March, 1848, the fires of social upheaval swept the greater part of Europe.

Again it was in the Days of March, 1871, that the people of France rose against their oppressors and proclaimed the Paris Commune. That gigantic attempt toward a social revolution failed after two months and was drowned in blood. A certain statesman of France said, as the Versailles hirelings were murdering the hekatombs: "We can never kill enough of them." He may have fancied that the revolution could forever be extinguished in an ocean of blood. What folly! The reaction had thrown down all barriers, trampled all considerations under foot, and let loose every imaginable terror, yet utterly failed to quench the revolutionary fire of even a woman's heart-LOUISE MICHEL, who had fought on the barricades, was dragged through the streets with the captured Communards, beaten with gun and bayonet, and finally thrown into prison. Proudly and defiantly she faced the horrors of the penal colony at Caledonia, endured persecution and agony, and finally returned to France as unbroken in spirit as before. What she had suffered in prison had only served to make her stronger and surer of her convictions. "Thereis a curse upon power," she said upon her return; "therefore I am an Anarchist."

It was again in the month of March, in the year 1881, that Tsar Alexander II. was called to account. Severest oppression, saints, strict censorship, base espionage, and brutal Cossacks-all these could not save the Tsar from the avenging bomb. There is necessity and justice in the revolutionary acts.

Though sometimes, in our hours of darkness, it may seem as if the oppression of man is an eternal institution, we soon find consolation in the thought that resistance to tyranny is no less eternal.

The Days of March bear witness that ignorance and patience have their limits. They show us that right and liberty are no mere fancies in the misty distance, but that they can be translated into life, realized in the present through acts and deeds.

These Days teach us that there exists no institution whose continued existence is guaranteed by charter or patent. They have torn the veil of political compromise and diplomatic finesse, and demonstrated the power of the multitude, which-in spite of all apathy and systematic obscurantism-still sets in motion the Weltenrad. These Days prove that deeds are more comprehensive than theory.

In December, 1856, John Brown appeared before a committee of the legislature of Massachusetts, to champion the cause of the slaves. But already in April of the next year he provided himself with ammunition, fully convinced that the legal procedure would merely sidetrack the issue, without touching the vital problem.

Thus the suffering masses clutch at one failing hope after another. They place their fate in the hands of governments, political parties, quacks, and reformers, till there grows up within their midst an energetic minority, which sees through the deceptive game and resorts to direct action. Strictly speaking, it can be said only of the Days of Revolution that the people act by themselves and for themselves.

The most vital initiative, the best impulses proceeded in the March Days from this minority, which, in times of struggle, becomes the interpreter of the sufferings and wishes of the multitude.

One feels almost an utopian when speaking hopefully of the Revolution in these epigone days of political horse swapping, petitioning, and pale theorizing. Is not everything quiet and orderly? Do not the rich wax steadily richer, their luxury more snobbish? Are not governments growing more invasive, the laws more numerous, and do not the masses continue to gnaw contentedly at the bones of reform thrown at them instead of good meat?

And yet, the Days of March are not in vain on the calendar of history. They point the way to the springtime of humanity. The memory of those Days sheds warmth and inspiration into the heart surcharged with disgust at all "golden rules," "good arguments," and "the only correct scientific methods."

THESE lines are in tender memoriam of John Most, who died in Cincinnati, five years ago, on the seventeenth of March, 1906.

In the year 1882 Most came to America, as an exile, and continued the publication of the Freiheit, whose existence had been made impossible in England. After the execution of Alexander II, on the thirteenth of March, 1881, Most voiced his hope in a leading article in the Freiheit\ that all tyrants may thus be served. That article proved too much for the much-boasted-of British freedom. Prussian and Russian spies and diplomats intrigued an interpellation in the British Parliament, as a result of which Most was indicted for "inciting to kill the reigning sovereigns." The court sentenced our comrade to sixteen months at hard labor, and life in the prison of free England proved a veritable hell.

Most had previously been incarcerated in German and Austrian prisons, and his treatment there was always that of a political prisoner. In free England, however, he found himself treated even more brutally than the ordinary thief or murderer. His complaints against the barbaric methods elicited the sole reply thatthere were no political prisoners in a f ree country like England.

When he had paid the penalty for the free expression of his opinions, John Most was invited, immediately upon his discharge from prison, to come to America, there to begin an energetic propaganda along revolutionary Anarchist lines. This comradely invitation was signed, among others, by Justus Schwab, whom most of our old-time comrades no doubt still remember.

Most followed the call. An enthusiastic reception meeting in Cooper Union, in which thousands participated, was his greeting in the new land. A tour of agitation followed, during which Most succeeded in organizing a large number of propaganda groups among the German-speaking workingmen.

Most was the first to initiate, on a comparatively extensive scale, the propaganda of Communist Anarchism in America.

The German element in this country was at that time far more mentally alert and energetic than it is to-day: the Bismarckian muzzle-law, the expulsion of hundreds of socialistically inclined proletarians, the suppression of Socialist literature, and the brutal police persecution made the thinking workers rebellious. The lines between governmental and revolutionary Socialism, and between the latter and Anarchism were not so sharply drawn at the time when Most, the fiery agitator of the social revolution, arrived in America. He was an orator of convincing power, his methods direct, his language concise and popular, and he possessed the genius for glowing word-portrayal which had f ar more effect upon his auditors than long theoretic argumentation. He lived and felt entirely with the people, the men of toil. The great tragedy of his latter years was that the very people he loved so well turned from him, many of them even joining the general howl of the capitalistic press, which never abated its denunciations of Most as a veritable monster of degradation and blood-thirstiness.

In the meantime there widened the breach between the ballot-box Socialists on the one hand, and the revolutionary Socialists and Anarchists on the other. Many of those who bad so enthusiastically welcomed Most on his arrival in America, joined the ballot-box party andnow even denounced our comrade because he persisted in warning the people against the game of deception called politics. In this respect hespoke from personal experience: as former member of the Reichstag he felt convinced that parliamentarism could never serve as an aid in the emancipation of the working class.

The American labor movement followed its course. It was- able to stand a Powderly, and it has not even now grown strong enough to rid itself of men like Gompers and Mitchell. Naturally there was no room in it for a Most, a Parsons, a Spies, or a Dyer D. Lum. Gompers, a rising star on the labor firmament, may indeed not have been averse to making use of Lum's superior intellect and experience, even to the extent of signing his articles, it is said. But after he had attained bureaucratic power, he found it more politic to withdraw from such compromising associates.

The German movement, in particular, gradually grew weaker. The atmosphere of this country is not very conducive to the mental development of the Germans; as a rule, they lose here all incentive to intellectual pursuit. They either conserve the ideas they have brought over with them, till these become petrified, or they entirely throw idealism overboard and become "successful business men," philistines who are far more concerned with their little house and property than with the great events of the world.

Under these circumstances his exile was growing more and more unbearable for Most, his hounding ever more severe and base, the indifference and apathy of the Germans more impenetrable.

His friends had told Most, upon his arrival: "Here, at least, you are secure against imprisonment." Most had waived the remark aside, as altogether too optimistic, saying that it was only a question of time when he would come in conflict with the sham liberties of the Republic. He was only too justified in this view. When, in the eighties, the waves of the labor movement rose to exceptional height, and the proletariat began preparations for a general strike to secure the eight-hour day, the plutocrats and financiers grew alarmed. "Order"that is, profits-seemed in danger. The lackeys of the press were mobilized to denounce to the police and the courts every expression of rebellious independence on the part of the working people.

In April, 1886, there took place in New York a large meeting, addressed, among others, by Most, who called upon the audience to prepare and arm themselves for the coming great struggle. The speech was taken down stenographically and submitted to the grand jury, which found indictments against John Most, Braunschweig, and Schenk. On the second of July, judge Smyth condemned Most to one year's imprisonment in the penitentiary and five hundred dollars fine, while the other two comrades were doomed to nine months' prison and two hundred and fifty dollars fine.

It was the old wretched method. The police of various cities had systematically interfered with the numerous strikes and committed repeated assaults upon the workingmen, establishing "order" in the most brutal manner. The violence of the police naturally resulted in bitterness, riots, and killings. But instead of calling the uniformed ruffians to account, the authorities fell upon the spokesmen of the movement, marking them as their victims. The crimes of the guardians of the law were "legally" laid at the door of the Anarchists: in New York, upon Most; in Chicago, upon Spies and comrades, who-eighteen months later-paid for their love of humanity with their lives.

It became evident that freedom of speech and press was not tolerated in the Republic and that it was as severely persecuted in "free" America as in Germany, Austria, and England.

That was not Most's only conviction. He was repeatedly condemned to serve at Blackwell's Island. The press had so systematically lied about and misrepresented his ideals and personality that the "desirable citizen" came to regard our comrade as a veritable Satan. Especially were the German papers venomous in their denunciations and ceaselessly active in the manhunt against one who had sacrificed everything for his ideals.

When McKinley was shot at Buffalo, the Freiheit happened to reprint an article from the then longdeceased radical writer, Karl Heinzen. The article had no bearing whatever upon American conditions, and it was the greatest outrage and travesty upon the most elementary principles of justice that Most was condemned to serve nine months inprison-for reprinting an article written decades before. The New York Staatszeitung, "leading organ of the German intelligence," bravely assisted in this shameful proceeding by the most infamous denunciation.

Yet all this persecution and suffering Most could have borne much better than the growing apathy of the very elements to whom he was appealing. He found himself more and more isolated. The struggle for existence of the Freiheit, and his family-grew more difficult. He had dreamed beautiful dreams of the masses who would march side by side with him against the bulwarks of tyranny. And now he discovered himself a revolutionary free lance, standing almost alone. With grim humor he wrote in the Freiheit: "Henceforth I shall no more say 'we,' but 'I.'" In spite of it all, however, he fought bravely to the very end. His courage and Rabellaisian humor never forsook him. In the latter years there was even a noticeable improvement in his literary originality. After all, in the words of the Chantecler, "it is beautiful to behold the light when everything around is enveloped in darkness."

ANARCHISM-The philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.

ANARCHIST-A believer in Anarchism; one opposed to all forms of coercive government and invasive authority; an advocate of Anarchy, or absence of government, as the ideal of political liberty and social harmony.

ANARCHY-Absence of government; disbelief in, and disregard of, invasion and authority based on coercion and force; a condition of society regulated by voluntary agreement instead of government.

To love to live-I choose this as my life,

The world is full of chatter, cheap and vain,

And painted sights and foolish paven lanes where people

moil at pleasure,

Getting none, returning yet again for naught and less

than naught--

And o'er-plussed emptiness of heart and soul

Which makes a mock of life and turns it sour.

All this I pass; not prudishly, as one who fears to mix

with men,

Nor scorning human things,

Nor in a cloister mood, seeking aloofness and some mys-

tic spell

But rather in a thirst for redder wine,

A crave for passions that are ne'er outworn,

A lust for one good hack at old Convention statued in

the Square.

To those who love the groove, the patterned task, the

vested rights,

I say, adieu.

Give me the thing to do that's not been done, That helps my kind, and yields my spirit wide egress, The ax upon the beech to mark my way, A golden sunset from behind the rugged hills, And, then, should the gods allow, A white arm round my neck entwined

And on my lips the kiss of Her who understood and

shared.

--Selected.

THE Trail of Life is like a beautiful woman, full of caprice and contradictions. Now it carries you to the sublime heights of expectation, now it hurls you to the very depths of despair, according to momentary whim. Yet like the heartless beauty, the Trail stands in all its radiance, ever luring one to new exploits.

Since we started on this journey the oscillations between hope and despair have repeatedly made us want to give up; but who can resist the Trail? Good or bad, success or failure-the tempteress calls, and poor mortals must follow.

DETROIT proved too weak for the large dose we had prepared for it. Six English meetings were more than the city could stand, its energies being sapped up by the Lady of Rome. Detroit is strongly Catholic; how can one expect to penetrate her tightly sealed mental channels . Yet there were a few faithful, eager for life, who attended every meeting and procured a liberal supply of intellectual ammunition. We realized only too late that four of the six evenings might have been employed to better advantage in nearby towns. We mean to make good on some other occasion.

ANN ARBOR again brought out a large array of students, less vicious than last year, but still very boisterous, especially on the evening of the lecture on Tolstoy. The sage of Yasnaya Poliana knew the emptiness of what passes for education to-day. His serenity would therefore not have been disturbed by the Ann Arbor demonstration of "learning." Not being quite so passive as our great Russian, it required much effort to keep sane in Bedlam; nor am I quite sure that I did. But, with lunatic luck, I succeeded in making the students think me the only sane person in the crowd. They toned down considerably at the end, asked a number of good questions, and-what is more-they did not break the chairs, nor raid the literature table, which was a decided improvement on our last year's experience.

The Keystone fraternity, keenly conscious of the shameful outrage on free speech in the City of Brotherly Love, invited us to break bread with them, as a sign of sisterly good-will. The wideawke spirit among these Pennsylvania boys has almost made me feel kindlier toward that Clay and Reyburn hunchbacked city, Philadelphia. Our last year's visit has helped to fertilize the soil. Prof. R. M. Wenley announced a course on Anarchism, of which the first lecture has already been delivered before a large audience. I am not conceited enough to assume that I induced the course, but that we have helped to arouse interest and to prepare the students for the "shock," is no doubt true.

GRAND RAPIDS furnished a new experience, doubly pleasant because of the opportunity it offered to meet once more our ex-soldier, William Buwalda. Our readers have probably been wondering what has become of our friend after his release from the tender arms of the government.

William Buwalda has exchanged the iron bands of mental deception for a free and broader outlook upon life, while his soul, dwarfed for fifteen years by the soldier's coat, has since expanded and blossomed out like a flower in the fresh and unrestricted air of mother earth. Our comrade has been left with an old mother to look after his father having died last year. He often longs to go back to the world and to more vital activity, but with his usual simplicity he said, "What right have I, as a free man, to inflict burdens upon others that I am unwilling to carry?" Therefore he remains to take care of the old lady; yet he has not become rusticated. On the contrary, William Buwalda has used his time well, not merely for extensive reading, but for the absorption and assimilation of our ideals. The old Dutch mother, the kindly hostess moving about in her quaint Dutch surroundings, was like a study of Rembrandt. It made one feel far removed from the mad rush of American life.

Buwalda's efforts for the Grand Rapids meeting proved a great success. It was one of the few splendid affairs of this tour.

CHICAGO, with her thousand sinister memories clutching at one's soul, is anything but an Eldorado. The gloom was increased by miserable weather, truly Chicagoan-wind, rain, and mud. The press, including that yellow sheet, the Daily Socialist, maintained a conspiracyof silence, and most of the preparatory work being done by one comrade, Sam Sivin, a stranger in the city, the prospects, too, looked muddy. Worst of all was the thought of having to go back to Hod Carriers' Hall, a place that would have affected the vocal chords of the trumpets of Jerico. It seemed to make the Chicago visit almost unbearable. But perseverance and lungs carried the day.

Our six English meetings brought out an average of two hundred people, which was very remarkable, considering the obstacles. Brother Reitman, with his usual mesmeric methods, disposed of a phenomenal quantity of literature. The Jewish meetings were, as usual, very large. Last, but not least, was a small but interesting meeting arranged by a group of Lithuanians, whom I addressed on the "Social Importance of the Modern School."

Credit for the hardest work is due chiefly to the indefatigable efforts of Sam Sivin and his friend Bessie; but there were also others who helped most faithfully: Edith Adams, our motherly Dr. "Becky" Yampolsky, our future Medicus Stein, and Comrade Lankis. Dr. J. H. Greer was the guardian angel. He turned his office into an E. G. headquarters, constituted himself ticket and book seller, and acted as knightly host to drive away the spooks, thus helping one to forget the sins of the Jungletown.

My greatest regret regarding Chicago is that I failed to interest our friends in the Kotoku Memorial. There was a lack of speakers; besides, Japan is far away; even Anarchists do not easily overcome distance.

URBANA, the seat of Illinois learning, is like unto the city of the German proverb, where people neither sing nor drink. It is a prohibition town; no wonder the mental lid is down tightly. Only a few students and professors turned out, but they, too, were as dry as Urbana.

The PEORIA meeting had been arranged in one day, in a hall on the outskirts of the city. We were therefore not disappointed in the size of the meeting. Yet while Urbana and Peoria gave small returns in proportion to our efforts, we are glad that we went there. We have driven in the wedge and are sure to meet with greater success next time.

ST. Louis. It seems almost like an idyl to come to the city after the desert of Sahara through which the Trail has led us for nearly two months. But, then, why should not St. Louis prove a rare spot, with Anheuser-Busch and William Marion Reedy as the great attractions. I do not know whether the city could do without Anheuser-Busch, but I am sure it would never be the same without Reedy, who is indeed a fountainhead of wisdom, rare humor, and good fellowship. To realize his importance for the intellectual life of St. Louis, one must have been here and followed his work. Thus with our "Hobo" I must say, "Reedy has put St. Louis on the map." With such a staunch sponsor and with the assistance of other friends, gained through Reedy's efforts, the work in St. Louis proved smooth sailing.

Three meetings at the Odeon Recital Hall were the very best so far, especially the meeting of March 1st, on "Victims of Morality," which brought out the largest American audience we have ever had outside of California. The literature sale represented a regular bargain counter, with Ben Reitman and several assistants strenuously busy supplying the demand.

The venture to arouse the ladies who think they are thinking was less successful. It was an unusual venture, to begin with, and as some of our comrades will no doubt say, apostatic on my part to consent. Two lectures in the most exclusive club hall of St. Louis, the Women's Wednesday Club, which resembles the Sorosis of New York:-a parasitic class of women who do not know what to do with their time. I was not at all in doubt as to the numbers that might come to such an affair. I consented to the proposition by our good friends, quaint little Alice Martin and William Marion Reedy, because of the chance it offered to tell those ladies what I thought of them.

"Tolstoy" and "Justice" were chosen-as "fit" subjectsfor the occasion: themes that contain enough revolutionary material to make the dear auditors anything but comfortable, and with E. G. as the speaker, they certainly "got their money's worth," the price of admission being one dollar. I should not care to make a practice of speaking before the Wednesday Club audiences. Not that I fear to be contaminated. I feel, with Gorki, that ours is a puny age, full of puny people who have not even the vitality to commit great sins. It is the mental apathy of the audience at that place which is so disagreeable, like the sight of dry old bones. I could forgive the rich Americans their money; but their dullness, never. The latter will save me at all times from "breaking" into society. Much rather should I prefer to break into jail. It is a much more interesting pastime. Yet the experience at the Wednesday Club had also its humorous side, and I wouldn't have missed it for anything.

Our dear old Comrade Harry Kelly, who left for the Coast after my Sunday lectures, gave the preparatory work the old revolutionary flavor. Ada Capes, Kapicinell, and other friends made me feel, by their devotion, as in olden days when there were fewer personal quibbles and greater zeal for our cause, so sublime and all-absorbing.

What a tremendous power one great individuality may exert is best proved by the new tone of the St. Louis press, created entirely by Mr. Reedy. Not a single paper has indulged in the old-time sensational methods. The reports have been accurate and the editorials unusually analytical. A complete revolution, one might say, judging from the following editorial in the Times:

Miss Emma Goldman, who made addresses in St. Louis yesterday, succeeded in voicing her sentiments without shocking any one very much, apparently, and without necessitating any calls for the trouble wagon.

It becomes apparent that Miss Goldman has a good many ideas which are sound, even though she may have others which are shocking enough; and it may be that those who disapprove most of her and her teachings are those who know least about her and what she has to teach.

There are a good many articles in the Goldman creed which might be given serious thought, and nobody would be any the worse for it. When she maintains that education of the stereotyped kind is not the right kind of education, she only affirms what many highly reputable thinkers have pointed out in a gentler fashion.

When she states her belief in the theory that there are no bad boys and girls, she is in line with the convictions of many a highly praised philanthropist. What is judge Ben Lindsay's creed, except that there are no bad boys and girls?

The trouble with this extraordinary woman is that she is a revolutionist, instead of an evolutionist. She is in a hurry; whereas the wisest men and women know that haste makes waste. Not one of the points made by Miss Goldman in her speeches Yesterday but is being put forth in gentler terms by good people everywhere. But others are encouraged when they realize what growth has been recorded in twenty years-in ten years.Miss Goldman is impatient because she cannot see great advancement since yesterday. Perhaps it is a matter of temperament, rather than of philosophy. Perhaps Miss Goldman is unfortunate only in respect to her temperament.

If our work had accomplished nothing else, this change of sentiment would justify all the hardships and bitter- ness most of us have and are still passing through. The Trail may i have a thousand whims and caprices, but it also has great charms. It is so alluring, one must follow it up to the very end.

I still have two Jewish meetings to address in this city; two lectures in Staunton, I11., before the miners, to which I look forward with great interest; also a meeting at Belleville, Ill., where our martyred Chicago comrades had fought more than one battle.

While MOTHER EARTH will be in the making, we shall have visited the Socialist citadel, Milwaukee. Will it survive us? Also Madison, Wis., where our last visit aroused so much discussion, especially among the students. March 15, 16 and 17 we will be in St. Paul; March 19-22 in Minneapolis. All information can be obtained through F. Kraemer, 1023 Marshall St., N. E., Minneapolis, Minn. March 24th, Sioux City; March 26th and 27th, Omaha, Neb. After that, Des Moines and Kansas City, for ten days.

EMMA GOLDMAN.

By VOLTAIRINE DE CLEYRE.

I HAVE read, in the last issue of MOTHER EARTH, Bolton Hall's opinion on the mixed blessing of discussion after meetings with interest, and-disagreement; mixed also.

I agree that a meeting of fifty with a good discussion is better than one of two hundred and fifty with none; but with a bad discussion-nine times in ten it is a bad discussion-meeting of two hundred and fifty and silence is preferable.

For I do not agree that "almost anything is better than silence"; sometimes silence is better than almost anything; particularly the silence of a "buffoon." Nor do I consider newspaper notice such a desirable thing as to be thankful for it at the cost of misrepresentation. If a meeting of fifty people enlightened by a discussion is better than one of two hundred and fifty without it, it is also better than two hundred thousand giving a cursory glance at a misrepresentation.

Also I would like to know what evidence Bolton Hall has that the best part of the audience sizes up the discussion well. It may be true, quite likely it is, but how does he know?

So far as I see, the real substitute for the after-benediction gathering is not the public discussion, but what we in Philadelphia used to dub "the adjourned meeting." That is the time when the timid and the reticent forget their timidity, and say their say. And it is really always far more interesting than the chairmanized discussion. For all that, I still think the evil of shutting off discussion is probably greater than the evil of "hot air."

One comrade has suggested that the lecture committee, expressing itself through the Chairman, reserve the right to have discussion or not; that a good lecture be left for "the gathering around the stove"; but an inadequate-lecture, or a poor one, be completed or rectified through a select discussion, such speakers being called upon by the Chairman as he knows are able to make good the deficiency.

The trouble is, this gives too much discretion to the Chairman (though as every one knows who has had experience in meetings such discretion is always exercised,more or less, if the Chairman is acquainted with his business. And as a member of the audience I have sometimes been grateful to him for his temporary blindness, or other symptoms of "benevolent despotism"). However, as Gail Hamilton once wrote: "I want my husband to be submissive without looking so"; I want the Chairman to be a despot without openly proclaiming himself such,-which is a very frank avowal for an Anarchist! I should be afraid to make it did I not know that "around the stove" pretty much everybody makes it. But as we all cling to our favorite phantoms, none of us wants the Chairman invested with Dictatorial Powers, notwithstanding our appreciation of the eccentricities of his eyesight; so I fear my comrade's proposition is not acceptable.

I should be glad to hear from others, not only as to the original question, but as to the incidental point of Mr. Hall, that newspaper report is always desirable, even though it be misrepresentation.

Because they could not achieve the Right Way, people

acquired benevolence.

Because they could not achieve the right benevolence,

people acquired charitableness.

Because they could not achieve the right charitableness,

people acquired courtesy.

Because they could not achieve the right courtesy, peo-

ple acquired good manners,

Because they could not achieve the right good manners

people acquired good works.

Because they could not achieve the right good works,

people acquired law-abidingness.

Because they could not achieveright law-abiding-

ness, people made laws.

This shows how far even perfect laws would be from

the Right Way.

But there cannot be perfect laws;

There cannot even be good laws.

From the Chinese of Lont Lee.

By Wm. C. OWEN.

A TIME-HONORED Latin proverb has it that when war breaks out the voice of law grows silent. I am certain that in politics the voice of truth is drowned by clamarous bids for votes, and it does not seem to matter what politics they are. Here is the Socialist party, for example. If Socialism means anything it is that collectivist ownership for use shall take the place of private ownership for profit. There can be no doubt of this, and modern Socialist literature is to a great extent one song of triumph over the extent to which private enterprise is being driven to the wall. Yet here, in California, the party's candidate for governor, touring the State in a much advertised red car, kept assuring the farmer that Socialism, while freeing them from the transportation and moneysharks, will leave them in possesion of their private farms, to be worked, as now, for private benefit. A desperate effort of my own to set this matter straight almost produced a riot, and never can I find anything but violent contradiction when I tell Socialists they belong to a governmental party. Nevertheless, in a recent number of the Appeal to Reason I find this editorial answer to a question as to what is to be done if the capitalists should decide on a general lock-out: "If they were to close the shops it would be as good a thing as we could ask. Then, under the plea of emergency, we could take possession of the shops and set all the wheels to moving at once under GOVERNMENTAL MANAGEMENT." To fish for votes by repudiating your party's cardinal principle seems to me at once the most despicable and suicidal of policies.

My own experience with the rank and file of the Socialist party is that intellectually it has not the remotest conception of where it is actually at, but that all its aspirations are toward Anarchism' . Invariably private conversation with members brings out the declaration that all they want is equality of opportunity, and that the less government they have the better. But let us not deceive ourselves. That may be the aspiration of the proletarian, sick to death of the authoritarianism he learns from the policeman's club, but it is not the aspiration of the preachers and lawyers who have crowded into the party and are doing nearly all its talking, because talking is their trade. Almost invariably the preacher's ruling passion is to lay down the law for others to obey; almost invariably the lawyer longs to regulate the lives of others; and such leaders naturally seek to form a centralized society, of which they shall be directors.

In Los Angeles the Single Taxers are trying to resurrect themselves, and surely there was never time or place wherein they should be more alive. To boom the natural resources of the country, thereby attracting immigration; to shear such immigration to the skin by continuously raising the admission price to those monopolized resources-this has been the game played unceasingly by the moneyed class since the city passed out of the village stage. Never was it played so relentlessly, however, as at present, for we have entered on an era of frenzied municipal enterprise, anticipating the rush of labor that will come with the completion of the Panama canal. Millions are being spent, south of the city, on harbor improvements, and land speculators gloat daily over the real estate ticker as it records the advanced value of their holdings. North of the city gigantic sums are being invested by the municipality in the development of water, and a group of land cormorants is becoming multi-millionaires.

Los Angeles is of interest to the great world of social agitation only as she points a moral and exemplifies a principle. It is because she illustrates with unusual clearness how rotten is the sham of public ownership and operation, while land monopoly remains intact, that I give her, and her Single Tax club, publicity. This craze for municipal-improvements is the undercurrent of the Socialistic tide, and it is crushing us with bureaucracy and land speculation; digging the gulf between Dives and Lazarus wider and deeper than it was ever dug before. If they could wrench themselves free from what seem to me side issues, the Henry George men might do noble work. As it is, their "cat" has been smothered out of sight and hearing.

By C. L. JAMES.

(Continuation.)

There was also a dispute between two great Fathers of the orthodox economic church, Ricardo and Malthus as to whether Rent cuts into Profit and Wages. Malthus denied that it affected either. Ricardo, by asserting that it reduced both, supplied the premises of an important Socialistic school whose bestknown representative is Henry George. The fallacies which make these controversies possible appear to me very largely founded in confusion of thought and language between such terms as (aggregate) rent and rent (per acre), interest (aggregate) and (per cent.), even real wages and nominal, though that is acknowledged to be a vulgar error. But they have a deeper root. The orthodox economists, having contracted the habit of generalizing from the capitalist's standpoint, are rarely able to see any other part of an universal truth than what concerns the capitalist, as such. And the Socialistic writers have not been able to correct them, because they, too, general 'zed from a special standpoint. Endeavoring myself to set both right by taking the Standpoint of Universal Man, or the Consumer, I shall most cheerfully acknowledge every anticipation I can find: for it will give me an opportunity to show that a view too limited and partial was what kept from the truth men who often got so very near it.

14. Rent, Profit, and Wages, are commonly assumed to be the shares in Distribution, falling respectively to landlords, capitalists, and laborers.13 But surely there are others. The share which falls to thieves is much too important to be justifiably ignored, if among thieves we include bad governments, corrupt monopolies, pestilent sinecurists, warriors employed in anything else than defense of their own countries, and these are, most deservedly, so classed by the orthodox Economy, which was the precursor and almost became the phoenix progenitor of Anarchism. This share is not like that of children, nursing mothers, beggars, unproductive laborers, who can get only what the producers or the producer's exploiters have had first. If conquerors and their creatures be thieves, as orthodox Economy teaches, the thief gets his share before the producer. There is also an impersonal sharer, Waste, which devours not what the producers choose to give it, for that would be nothing, but all it -can take against their will. Floods, flames, moths, rust, mice, kings, nobles, and pirates, must have their undivided share first. The producer gets only what they leave. The Socialistic writers are not insensible to part of this truth. Before Saint Simon gave them anything like a scientific method , they perceived that existing institutions were founded by barbarians whose, only trade was war, and that the taint of origin pervades them all. Adam Smith partly saw this, too."14 The reason neither he nor they have adequately reasoned from this historical premise, is that both the main economic schools were in a hurry to begin generalizing either from the capitalist's standpoint or the laborer's. Waste and Plunder, so important to the Consumer, i. e., to man, as man, were dismissed with the remark that they took only from the gross product, and that the laws of the net could be ascertained without considering them. But if, as Adam Smith, all Socialists, and all Historic Economists, perceive, the landlords and capitalists derive peculiar powers from government, an institution whose original purposes were war and Plunder, it evidently is not correct to say that we can get at the law of their share in Distribution without. first considerfrig the laws of Plunder.

15. This error, springing direct from the Original Sin of Political Economy, has been the fruitful parent of others. The definition of Capital as wealth employed to produce more wealth, is incorrect. The wealth consumed in war is not employed to produce wealth but to destroy it; and a bond given by the government to those who lend it money during war is not wealth at all. But to say, as Henry George does actually say, that the bonds of a government are not Capital, is to deny that Rothschild is a capitalist-a palpable reductio ad absurdum; for he is a typical capitalist-a capitalist who is nothing else than a capitalist, whereas most capitalists are also landowners and laborers; which embarasses us when we wish to class them, while he is classable at once and forever as a capitalist. And, as all Capital is not wealth employed to produce wealth, so much wealth employed to produce more wealth-for example, the tools belonging to a man who lets out the work he does with them-are capital in no ordinary tenable sense. For a correct definition of Capital we are indebted to Karl Marx. Capital is that which acquires Surplus Value, or a share in Distribution not due to labor. It may be wealth employed to produce wealth, but is not necessarily. It includes, therefore, slaves, accounts bearing interest, and Land, though this is a peculiar kind, needing, frequently, to be distinguished with much care from (other) Capital15." This definition certainly has the disadvantage of leaving us without a short term for wealth employed to produce wealth, After considerable embarassment from this lack, I determined to employ the symbol W. P. W.; and I find it very convenient. I shall maintain that W. P. W., as such, works, though it may be Capital, in quite the opposite way to Capital, as such. Capital is, in Wall street phrase, a "bear": W. P. W. is a "bull." W. P. W. raises the value of labor: Capital, as such, always tends to beat it down. "Orthodox" economy, having thus committed a non distributis medii, in identifying with Capital what is only sometimes a part of Capital, and fallen into the ambiguity of using the word Capital in two inconsistent senses,16 proceeds to give an incorrect account of the process by which both W. P. W. and Capital are brought into being. Because under the existing "bourgeois" methods of production and trade, most Capital is W. P. W., and because the individual capitalist often17 becomes one by saving money, this theory, still failing to distribute the middle term, asserts that Capital is created by saving money. But in whichever sense the word Capital is to be understood, Capital existed long before there was any money to save. Does Capital mean W. P. W.? Then the forked stick of the Digger; the bow of a more advanced barbarian; a tame horse, dog, cow; a boat, a net, is Capital. What had saving money to do with making these? They were made not by "adding parsimony to production," but wholly by production, of that peculiar kind which is called Invention. Now, it is a truth of the first importance that the economic functions are always essentially the same-that they advance, not by creation but only evolution,-a "simple indefinite homogeneity" becoming a "complex definite heterogeneity." All W. P. W., from a raft to a Great Eastern, an Esquimaux sled to a Union Pacific R. R.; a bow to a quick-firing rifled cannon, is produced by Invention, and by nothing but Invention. All the processes of trade-the opening of new markets, the use of bills, notes, banks, stocks, clearing houses, were brought into existence by invention, and by nothing else. Money owes its existence to Invention and its use has very largely given way to that of credit, a somewhat later invention which is admitted to serve all the same purposes. An imperfect system of credit-exchanges still makes cash payments periodically necessary, and the great cash accumulations of bankers very useful; but of these accumulations only a very small part is due to saving; which, moreover, to give it all the praise it has, can accumulate nothing but money, could not do that if all the people tried to save, and would be useless but for that series of exchanges whose end is always unproductive consumption. To suppose an extreme casea favorite device in economic reasoning,-we have seen what not only would happen if all tried to save money-they could not do it, and they would all be poor-but what actually does happen where this process is approached, as in "Jewtown"-they all are desperately poor. Now suppose, then, that nobody saved money-that every one bought whatever he fancied-what would happen? Since it is evident that if a man who starts with nothing proposes to build or buy a house he must meanwhile abstain from gratifying many desires of a more evanescent character, there might be less substantial comfort than there is. But this does not seem to me quite certain, for the number of such men who build or buy houses has never been great; and, if we inquired into their antecedents we should be apt to find they differed from less provident neighbors rather in their natural tastes than their acquired habits. At any rate, there would then, as now, be productive labor, without which no man starting poor in a pacific society could gratify his desires at all; trade, without which only the simplest desires can be gratified; and invention, which is what improves all the means of gratifying desire. In short, the effect of parsimony even in assisting production of W. P. W. is much exaggerated.

(To be continued)

NEO-MALTHUSISMO Y SOCIALISMO. Alfredo Naguet y G. Hardy. Barcelona, Spain.

THE AMERICAN HOUSE OF LORDS. Morrison 1. Swift. The Supreme Court Reform League, Boston, Mass.

DIE LUGE DES PARLAMENTARISMUS. Pierre Ramus. W. Schouteten, Bruscelles, Belgium.

THE MAN-MADE WORLD OR OUR ANDROCENTRIC CULTURE. Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Charlton Co., N. Y. City.

MIMO SPOLECNOST. Jos. Kucera. Literarni Krouzek, Chicago, 111.

FABIAN ANARCHISM . Alexander Horr. Freeland Pub. Co., San Francisco, Cal.

THE CHASM. George Cram Cook. Frederick A. Stokes Co., New York

SINGLE TAX CONFERENCE, 1910. Joseph Fels Fund Commission, Cincinnati, 0.

THE MODERN SCHOOL. Wm. Thurston Brown, Salt Lake City, Utah. ADVENTURE. Jack London. The Macmillan Co., New York. ($1.50)

Footnotes

Footnote 13: I am loth, yet it may be needful, to spend space on such remarks as that the same man may be all three of these characters; or that the "best" land does not mean the richest, but that whose culture pays best, for whatever reason.

Footnote 14: "He says the origin of Rent is the desire of landlords, a privileged class, to reap what they did not sow. Ricardo assumed to correct him by giving that theory of its origin stated above.

Footnote 15: Even Henry George, than whom no writer has insisted more on the difference between Land and Capital, says that Land Value is only "Rent commuted, or capitalized."

Footnote 16: "That the orthodox economists are aware of something loose about their definition of capital, is evident from their plentiful disagreement.

Footnote 17: "I can hardly say as a rule. Of the money in even savings banks only a part is "savings," the rest representing trades' balances for which the depositors had no immediate use.

Back to Emma Goldmans Collected Work

Anarchist Archive

|