|

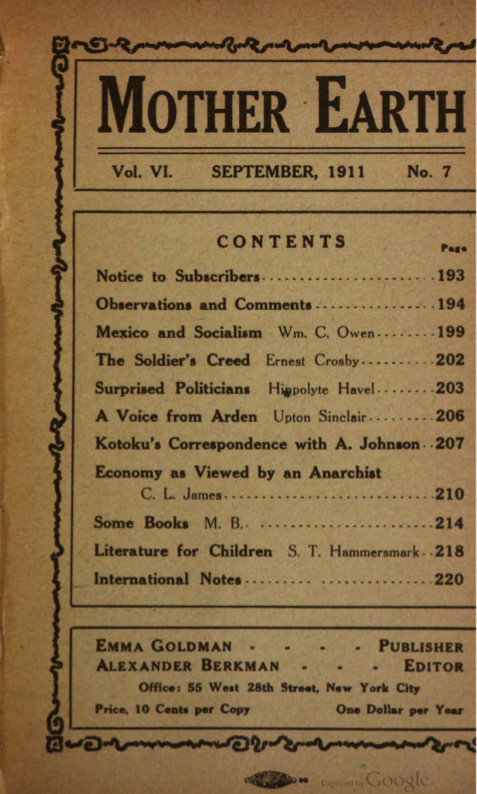

NOTICE

Though we are very reluctant to drop anyone from our lists, MOTHER EARTH cannot carry unpaid subscribers, since, even at best, it is published at a loss. Therefore we strongly urge our readers to send their subscriptions in AT ONCE.

SPECIAL OFFER

Thanks to the generous offer of Companion M. H. Woolman, we succeeded in enlarging our subscription list. But the magazine is still far from the self-sustaining point. In the hope of reaching that goal, we have decided to make this offer:

Anyone sending us three new yearly subscriptions before the expiration of the current M. E. year (closing with the February issue, 1912) will be entitled to a free copy of one of the following books, sent postpaid: (a) "Conquest of Bread," by Peter Kropotkin; (b) an autograph copy of "Anarchism and Other Essays," by Emma Goldman; (c) any dollar book carried by us.

We hope our friends will lose no time in availing themselves of this opportunity.

EMMA GOLDMAN

OBSERVATIONS AND COMMENTS

THE period of prosperity by the grace of Morgan is on the wane. Hundreds of unemployed crowd the parks, and many jobless men are vainly seeking work. The capitalist press sounds a warning against strikes and dilates upon the insecurity of the money market. Wall Street plans to send its champion commis voyageur Taft on an exhibition tour, that he may lull the growing discontent of the people by soft political phrases.

Do the Mammonists really believe they can abolish the social misery by the display of Presidential quantity?

* * *

TO counteract the yearly protest of labor against wage slavery, as manifested on the First of May, the representatives of the American plutocracy at Washington decided upon a legal holiday. Instead of repudiating with deserved contempt the holiday in honor of slavery, the conservative and law-abiding leaders of organized labor have submitted to the will of the politicians. Yearly we now witness on Labor Day the sad spectacle of the toilers celebrating, at the behest of their exploiters, and peacefully parading the streets.

Yet even this legalized holiday could be made the occasion of a mighty protest, if the so-called leaders did not suppress with smooth words the rebellious spirit of the workers.

If ever a protest of tremendous weight was needed, now is the time. Not only are the unions forced to wage a continuous struggle for their economic self-preservation: they are being robbed by capitalist judges of the last vestiges of their rights; the officials of one of the most important labor organizations are in peril of being railroaded to the gallows; the chief representatives of trade unionism are facing the probability of going to jail for contempt of court. A demonstration of strength would have surely been in place.

What, however, transpired? The usual parade, without energy or significance, lacking power and initiative, devoid of all revolutionary spirit. A pathetic spectacle it was, applauded and ridiculed by a curious mob. Fifty thousand workers march through the streets of the metropolis under the "protection" of the police department. National banners are carried, together with some meaningless transparencies. The band is playing rag-time, and the organizers and leaders of the toilers ride in carriages at the tail end of the demonstration, instead of marching, like real leaders, in the front. Not a solitary rebellious battle cry, not a single inspiring song. The most pathetic feature of all, the proletarians of Slavic and Latin origin are infected by the spirit of weakness and dulness. The men and women who in St. Petersburg and Barcelona, in Mailand, Lodz, and Liverpool, so enthusiastically participated in demonstrations and battles, here march at the order of their leaders like so many dumb sheep.

Such an attitude will never inspire respect in aggressive capitalism. The diplomatic leaders will probably realize it when it is too late,—when the imprisoned workers in Los Angeles have fallen a prey to the hangman, it will be too late, unless the workers lose their patience betimes, and sweep their cringing leaders out of their ranks.

* * *

PHILANDER C. KNOX, who had won his spurs in the role of Carnegie's lackey, and is now the representative of the foreign business interests of the commercial barons, is by no means a friend of revolutionists. Diaz, Madero, and Nicholas of Russia, are men to his liking. No wonder, then, that he longs to abolish the right of asylum for political refugees.

In reply to an inquiry by the New York Mexican Revolutionary Conference, Mr. Knox sent the following telegram:

Charles W. Lawson, New York.

The President has referred to this department the telegram dated August 7th, signed by Harry Kelly, Leonard D. Abbott, Milo Harvey Woolman and yourself regarding the alleged surrender to Mexican Government officials by authorities at El Paso, Texas, of Jose Maria Rangel, Priscilian and Ruben Silva and others. This information had already been conveyed to the Department and immediately upon its receipt the department instructed the American Consul at Juarez to investigate and report, and laid the facts before the Department of Justice for such action, if any, as the circumstances might warrant. It does not appear that any of the above-named persons is an American citizen or that the Mexican Government committed any wrong in obtaining possession of these persons; neither does it appear that the United States Federal authorities have had anyth1ng whatever to do with the alleged transaction. If these men are under detention by Mexican authorities, this department has no reason to believe that they will receive any such fate as suggested, and in view of the circumstances it is not perceived upon what international grounds the department could base intervention requested on their behalf nor support a demand for their return to the United States. Any official at El Paso guilty of kidnapping may obviously be prosecuted therefor. There is no evidence before the department whatever beyond the bare allegation of the fact to show that even if these men have been turned over to the Mexican authorities, such delivery was for punishment for political offences, and even if such proved to be the fact, it seems to be quite obvious that those who, whatever their motive, engage in rebellion against an established Government must be prepared to abide such legitimate consequences of their acts as the law of nations and an enlightened humanity do not forbid.

Knox,

Secretary of State.

We fear the protest sent to Knox and reprinted below will hardly change the attitude of the thick-skulled Secretary.

Hon. Philander C. Knox,

Secretary of State,

Washington, D. C.

We have received your message of August 10th relative to the imprisonment of Jose Maria Rangel, Priscilian, and Ruben Silva, and others in Juarez, Mexico, and note therein an admission which seems to us to contradict the very principles on which this government is based.

The Declaration of Independence especially declares that whenever any form of government tends to oppress the people under its sway, "it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government." Yet you say: "Even if these men have been turned over to the Mexican authorities . . . for punishment for political offences ... it seems to be quite obvious that those who, whatever their motive, engage in rebellion against an established government must be prepared to abide such legitimate consequences of their acts as the law of nations and an enlightened humanity do not forbid."

It would seem from your statement that the United States government now stands for the principles that political offenders can be turned to the government from which they escaped. Since when has our government adopted a policy repudiated even by monarchical governments of Europe? To be sure, it is quite obvious that rebels against established governments must be prepared to abide by the consequences of their acts. It is not so obvious that our government, itself founded upon rebellion, must needs assist the Government of Mexico or any other country to crush revolutionists merely because such government is established.

Whatever be the merits of the struggle in Mexico, the United States cannot without violating every American tradition aid the Mexican government to suppress those who struggle against the present order. We protest most emphatically against this interpretation of yours of our extradition laws, for if such interpretation be correct, our government is pledged to aid and abet every move of the forces of tyranny and despotism.

The Mexican revolution conference

Per Charles W. Lawson, Chairman.

* * *

THE claim of the Mexican rebels that the revolution in their country is not merely a political movement, but a great social upheaval, finds corroboration in the reactionary camp. The situation is considerably illumined by a bourgeois writer, Don Carlos Basave, in a contribution to the Catholic publication, El Pais. Among other things, the author says:

No mere political aspiration caused the masses to interest themselves in the revolution. Looking beyond that, the rural population saw that its final result would be the realization of an ambition always dear to its heart—that of becoming owners of the soil; recovering that of which it had been despoiled by powerful neighbors, able to cover up, more or less, their spoliation with legal formalities.

One may observe most clearly the aspiration to which I have referred, and cite concrete examples; for on numerous estates the country folk have settled down, not merely as armed bands but as cultivators, appropriating to their own use the growing crops. It has been found impossible to disperse them, and bargains of expediency are now being resorted to for the sake of keeping titles intact. The peasants are being recognized as renters, and, in some cases, as part owners. Similarly other hacienda owners have resolved on a policy of selling portions of their estates in lots, being convinced that there will be no return of the days when their influence was decisive, even when contrary to equity and justice.

"Land and Liberty" is the motto of the Mexican peons, guiltless of "scientific" Socialism. Together with the factory slaves they are working on the reconstruction of economic conditions by means of direct action. The politicians face the movement in utter helplessness.

* * *

EUGENE V. DEBS changes his colors like a veritable chameleon. The criticism of his stand against the economic revolution in Mexico has forced him to change his attitude. His assertion that the peon is not yet ripe for Socialism having been reduced ad absurdum by the brilliant arguments of our Comrade Wm. C. Owen, Debs is now moved to acknowledge his position as untenable. But he seeks to cover his retreat by laying the blame at the door of the Anarchists as if the latter were responsible for his fluctuations. It does him little credit that he attempts to justify his lack of intellectual stability by accusing the Anarchists of being boodlers and corruptionists.

* * *

AN interesting sidelight regarding the attitude of Socialists toward the negro problem is shed by the reports of Theresa Malkiel on a lecture tour in the South. She recites numerous cases, showing that the black men receive far worse treatment at the hands of Socialists than from conservatives. "To the everlasting shame of our Southern comrades," writes Theresa Malkiel, "they treat the negroes like dogs."

That is the result of a Socialist propaganda limited to vote baiting. No wonder that the party consists chiefly of national and racial philistines, moral eunuchs, and religious soul savers.

* * *

THE Revolution was conquered; the bravest of the fighters had perished on the barricades or were doomed to Siberia. The era of brutality toward political prisoners was re-established. When the protests remained unheeded, the heroic Sasonof, the executor of the popular will against Plehve, decided, with five other comrades, to commit suicide in the prison of Zarantui, in order to rouse the attention of the world to the persecution of the political prisoners.

This last act of brave self-sacrifice remained without effect. But now arrives the news that the Governor of the Zarantui prison has been shot. Lo! the avenging angel is not at rest.

MEXICO AND SOCIALISM

By Wm. C. Owen

IN Mexico, our immediate neighbor, to whom we are bound by a thousand ties, a revolutionary situation of extraordinary vehemence blazes into life. Within a few short months an absolute monarch, backed by a large army, is driven from the throne. In whole States, such as Morelos, the peasants take possession of the land and cultivate it for their own use. Churches, courthouses, and jails are burned, all prisoners being released and hailed by the masses as brothers and fellowworkers. In a word, a large proportion of the people shows a grim determination to have done with the entire existing regime—economic and political. Surely a remarkable situation!

Mexico's neighbor, the United States, has been for more than a generation past the home of bitter discontent. No country equals it in the savagery of its labor wars; nowhere has there been fiercer denunciation of predatory wealth and privilege. From no country, therefore, would one have expected so ready a response to the Mexican Revolution as from the United States. But when one looked round for the expected sympathy, where was it? When one waited anxiously for the revolutionists to gather round the standard, where were they? As a matter of fact, outside of the Spanish and the Italians, they were practically non-existent. To this day only the merest handful has been galvanized into life, thanks to the untiring efforts of a few.

For this there must be reasons, and it seems to me that the reasons can be brought to light, in part at least, by considering the case of Los Angeles, from which I write. Los Angeles, therefore, I propose to consider, but most unwillingly; for it brings me into conflict with men I have known for years and would far rather conciliate than oppose. For example, all my natural inclination is to boost Job Harriman, now running for mayor on the Socialist-Labor Union ticket, inasmuch as he is counsel for the imprisoned members of the Mexican Junta.

Whenever a radical lecturer comes to Los Angeles nowadays he or she immediately reports that there the opposed forces of labor and capital are drawn up in bitter conflict; that the McNamara-Times case, and the fact that the Mexican Revolutionists have their headquarters in Los Angeles, have made it, for the moment, the real revolutionary center of the country. The articles written to that effect would fill a library, and they are largely true, for here in Los Angeles there is a revolutionary situation, and labor throughout the country does recognize the conflict as likely to be determinative. Labor is showing that by pouring money into Los Angeles, and I read statements to the effect that the defense of the McNamara brothers will cost $800,000.

We have then, in Los Angeles, a revolutionary situation, generally recognized as such. We have labor throughout the country doing the best it knows to meet that situation. We have every Socialist in the land whooping it up for Los Angeles. "Action!" is the cry of the hour, and an examination of the action, taken and proposed, becomes a duty of the first importance.

What are Labor's ideas as to the way in which its present all-important fight should be conducted? First, it spends money like water on lawyers, an enormous array of whom is now at work endeavoring to earn fees that range from $10,000 to $50,000. Secondly, large sums unquestionably are being spent on "tuning" the much-execrated capitalist press through the medium of a press bureau which plays up from day to day the doings of the lawyers, that the public interest may not flag. Thirdly, a gigantic effort is being made to carry Los Angeles at the approaching municipal election, by combining the Socialist and Trades-Union forces. To head the ticket Job Harriman, a noted Socialist and one of the McNamara counsel, has been selected. Another Socialist, formerly a well-known editor, is in charge of the news bureau; everywhere the Socialists are phenomenally active, and the first big gun has now been fired, in the shape of a front-page, large-typed, display article in the Los Angeles Record—a capitalist paper, and unquestionably subsidized—with a heading that reaches all across the page and runs: "Who for Mayor? Job Harriman, of course.".

The Record has done its work skilfully; it has endeavored loyally to earn its money by urging everyone to vote "for Job Harriman, the Socialist candidate for Mayor, and for every other municipal candidate who stands for the same things he stands for." I am satisfied that it has inserted every argument Job Harriman and his Socialist-Labor Union combination want to have inserted. What do they amount to?

Nearly a column and a half are devoted to the demonstration that previous administrations, while promising the workingman everything before election, have forgotten him after election. The action of "big business" —much emphasized throughout the manifesto—in passing an anti-picketing ordinance and refusing to increase the pay of the aqueduct workers is given in illustration. Naturally we are assured that the Harriman administration will not play the workers false. Then follows this declaration; the one and only part of the manifesto which moves from vague generalities to positive assertion:

"We believe that the election of Harriman and such associates will bring the municipal ownership of ALL the public utilities nearer than anything else that could possibly be done, and that under their administration it would be impossible for any public service corporation to unload its plant on the city at an exorbitant price, or to make the city pay for water in its stock in order to get the plant. During the next few years many matters of great importance are going to come up in Los Angeles, and if 'big business' continues to control municipal affairs as it has in the past, the lot not only of the workingman, but of the small manufacturer and all others whose prosperity is dependent on the prosperity of the workingmen is going to become a mighty unhappy one."

That is all. I am not saying that the position taken is deliberately dishonest. I am quite willing to admit that it may be considered the best way of getting out the working vote. But I do say that it is preposterous to talk of such a movement as "revolutionary," and I point out that if this is the Socialist idea of the revolutionary action needed to meet an admittedly revolutionary situation, some of us need to revise our conceptions as to the Socialist party. For Harriman is supported enthusiastically by Socialists throughout the country, the entire party being buoyed up with hope that another Milwaukee may be created here in California. Moreover, Harriman is a most representative Socialist, has always been considered revolutionary, and ran on the same national ticket with Debs, being candidate for vice-president of the United States.

Meanwhile, looking at the Socialist party as it is showing itself under fire, and considering the influence it apparently exercises in labor counsels, I do not won-' der that a real revolution, such as that in Mexico, commands so little sympathy. To me, profoundly interested in the success of that revolution, the Socialist party is not a friend, but an enemy. I regret it deeply, but facts are facts.

* * *

THE SOLDIER'S CREED

By Ernest Crosby.

"Captain, what do you think," I asked,

"Of the part your soldiers play?"

But the captain answered, "I do not think;

I do not think, I obey!"

"Do you think you should shoot a patriot down,

Or help a tyrant slay?"

But the captain answered, "I do not think;

I do not think, I obey!"

"Do you think your conscience was made to die,

And your brain to rot away?"

But the captain answered, "I do not think;

I do not think, I obey!"

"Then if this is your soldier's creed," I cried,

"You're a mean unmanly crew;

And for all your feathers and gilt and braid

I am more of a man than you!"

"For whatever my place in life may be,

And whether I swim or sink,

I can say with pride, 'I do not obey;

I do not obey, I think!'"

SURPRISED POLITICIANS

By Hippolyte Havel

THE revolt of the British workingmen is one of the most encouraging and important signs in the struggle of the international proletariat for emancipation. Significant lessons may be drawn from this struggle. We beheld the triumph of the general strike idea and witnessed the downfall of political leadership. The upstarts of the labor movement, corrupted in the swamp of parliamentarism, were as much surprised by the revolt and the splendid solidarity of the wage slaves as their colleagues and masters of the capitalist camp.

Never before was there an opportunity to see so clearly and convincingly how little sympathy the socalled leaders and the political parties have with the man of toil, or how poor their understanding concerning the condition of the people and the latter's soul. They are blind to the revolutionary activity of the Anarchists, Syndicalists, and industrialists. What gross ignorance, for instance, is displayed in the editorial observations of the N. Y. Call:

"That the strike should approach the magnitude of an almost universal cessation of work, is hardly to be accounted for by any widespread and long sustained propaganda advocating the general strike. Certainly neither of the two bodies professedly representing the Socialism of England, have laid any particular stress upon it as a weapon in the labor struggle, nor has there been any special organization of importance advocating it outside these two bodies. Rather does it seem a spontaneous and largely unexpected revolt on the part of the workers, in which direct agitation and organization do not appear to have played a distinct part in bringing about."

The editor of the Call evidently knows nothing of any organizations outside the political Socialist parties of England. Is it sheer stupidity or the willful ignoring of facts? Perhaps the editor agrees with the London Times which seeks to explain the General Strike with this wisdom:

"Anarchy reigns and the so-called labor members of Parliament know nothing about the whole mad business. Indeed, the movement is said to be largely directed against them by agitators who have been less successful in public life than themselves."

Tom Mann, who together with Ben Tillett conducted the strike, turned his back upon the Socialist party about a month ago. In his resignation he gives the following reasons:

"My experiences have driven me more and more into the non-parliamentary position; and this I find is most unwelcome to most members of the party. After the most careful reflection, I am driven to the belief that the real reason why the trades-unionist movement of this country is in such a deplorable state of inefficiency is to be found in the fictitious importance which the workers have been encouraged to attach to parliamentary action.

"I find nearly all the serious-minded young men of the Labor and Socialist movement have their minds centered upon obtaining some position in public life, such as local, municipal or county councillorship, or filling some governmental office, or aspiring to become members of Parliament.

"I am driven to the belief that this is entirely wrong, and that economic liberty will never be realized by such means. So I declare in favor of Direct Industrial Organization, not as a means, but as the means whereby the workers can ultimately overthrow the capitalist system and become the actual controllers of their own industrial and social destiny.

"I am of the opinion that the workers' fight must be carried out on the industrial plane, free from entanglements with the plutocratic enemy."

No one enjoys greater respect among the workers of England than Tom Mann. Deservedly so: has he not been an active participant within the last twentyfive years in every struggle of the proletariat in England, Australia, and South Africa? Like so many other Socialists, he has become convinced through experience of the uselessness of parliamentary activity and he has learned the importance of direct action and the General Strike.

The methods which the Anarchists have been propagating for a score of years have finally triumphed in England. Thus an important bond has been formed between the toilers of Great Britain and the revolutionary movement on the Continent.

By means of direct action and the General Strike the English workers have accomplished more in a few days than their leaders have succeeded in doing in the yearlong "activity" in Parliament. They have not only carried their demands, but also caused tremendous injury to their masters, the capitalists. This strike, in which various organizations participated, involved not merely conciliation boards, but mainly practical demands: increase of pay, reduction of working hours, and the recognition of the right to organize—all of which have been won. Quite correctly the San Francisco Revolt remarks:

"Five days of the general strike in the British Isles has served to win the respectful and favorable attention of the British Parliament to the demands and needs of the workingmen involved in the mighty demonstration of class solidarity. A commission has been called which, ostensibly, is to "arbitrate," but actually is to come into existence with instructions all ready for it under which it will have but one thing to do, and that to adjust the hours and the pay of the militant workers in accordance with their demands."

Even such bitter enemies of the Syndicalists and Anarchists as the members of the Socialist Labor party must recognize the success of the direct Anarchist action of the English workers. Thus its London correspondent writes to the N. Y. People: "The moral value of the strike will prove lasting. More important than the commission inquiry is the discovery of the tremendous weapon possessed in simultaneous sympathetic strikes. It is likely to appeal to the workmen and procure thousands of recruits for the unions. A detached strike, financed by a single organization, will be abandoned as a rusty implement no longer serviceable, and the federated strike will be taken up as the method of redressing the grievances of the British workmen. They have learned from their first trial of strength that they have in their possession a better method of compelling the masters to make concessions and to reinstate strikers than they had heretofore. The general effect of the labor crisis has been the creation of a feeling of insecurity among capitalists and employers."

The confession loses none of its significance by the change of the General Strike into a "federated" strike.

A VOICE FROM ARDEN

August 17, 1911.

To Harry Kelly And Emma Goldman. -*

Dear Comrades:—I desire to make you acquainted with the following facts: George Brown persisted in discussing sex questions at a meeting of the Arden Club, a private organization. He was requested to desist and refused. The club then voted to deny him the privilege of its floor. He then persisted in speaking and broke up two meetings. He declared it his intention to break up all future meetings, whereupon the officers of the club had him arrested. I am a member of this club, but I had nothing to do with the action, and knew nothing about it until Brown was in jail. I was not present at any of the meetings in which these things took place. George Brown stated to me personally that his reason for having me arrested was simply in order to contribute notoriety to the affair. I might mention also that Frank Stephens was away from Arden when the affair took place, that he is not an officer of the club, and knew nothing about the matter.

I request the publication of this letter in Mother Earth. I should be perfectly willing for you to submit this letter to George Brown. I have no doubt that he will endorse my statements of fact.

Sincerely,

Upton Sinclalr.

KOTOKU'S CORRESPONDENCE WITH ALBERT JOHNSON

(Continuation.)

San Francisco, May 29th, 5 P. M.

Mr. Johnson.

Dear Comrade:—I came here to-day (afternoon). I regret that I could not call on you, because I did not know where you are.

I have composed a poem of farewell* in Chinese language. It is in style of ancient classic. I will write it on Chinese paper and send you. I think I can post it to-morrow. It will be addressed to the Alameda.

I will stay in Oakland till June 1st. On that day we are going to hold a meeting for the organization of Japanese Social Revolutionary Party at the Oakland Socialist headquarters.

Yours for the revolution,

D. Kotoku.

* Kotoku's sojourn in America lasted only a few months. He organized the Japanese workingmen on the coast and returned to his native land to continue his propagandistic work. H. H.

Japan, Dec. 18th, 1906.

Dear Old Friend And Comrade.

The winter has come, the leaves have fallen. It is, however, very fine weather. The sky is blue, the sunlight is warm. So I am very happy at my village home.

My wife went to the law-court to attend as a hearer to the trial of Comrade Osugi this morning. Comrade Osugi is a young Anarchist student and a best friend of mine. When I was in San Francisco he wrote to you in French language and Mrs. Ladd translated it for you. Do you remember it? Well, Mr. Osugi is now under the trial on the charge of "violence of the press law." He translated an article titled "to the conscripts" from a French Anarchist paper and published it in Hikari, Japanese Socialist paper. This anti-militaristic deed was prosecuted by the public officials. I am now anxious to hear the result of that trial. I think it will be probable the sentence of several months' imprisonment and the confiscation of printing machine. How good law and government arel

The most comical fact of the results of the late war is the conciliation (or rather embrace) of Christianity with Buddhism and Shintoism. The history of Christianity in Japan was until now a history of horrible persecutions. The Japanese diplomatists, however, earnestly desiring to silence the rumors caused and spread in Europe during the war that "Japan is a yellow peril" or "Japan is a pagan country," suddenly began to put on the mask of Western civilization, and eagerly welcome and protect, and use it as a means of introducing Japan to European and American powers as a civilized Christendom. On the other hand, Christian priests, taking advantage of the weakness of the government, got a great monetary aid from the State, and under its protection they are propagating in full vigor the Gospel of Patriotism. Thus Japanese Christianity, which was before the war the religion of poor, literally now changed within only two years to a great bourgeois religion and a machine of the State and militarism!

The preparation for the Socialist daily is almost completed. I hope the daily will have a success. The Japanese Socialist Party consists, as you know, of many different elements. Social-Democrats, Social Revolutionists, and even Christian Socialists. So the daily would be a very strange paper.

Most of our comrades are inclined to take the tactics of Parliamentalism rather than Syndicalism or Anarchism. But it is not because they are assuredly convinced which is true, but because of their ignorance of Anarchist Communism. Therefore our most important work at present is the translation and publication of Anarchist and Free-thought literature. I will do my best, and use our paper as an organ for the libertarian propaganda.

In China the rebellions and insurrections are spreading. The social and political conditions of China are just same to that of Russia in last century. I think China will be within the coming ten years a land of great rebellion and terrorism. A group of Chinese students in Tokio is becoming the center of Chinese Revolutionary movement.

Yours very truly,

D. Kotoku.

Yugawara, Sagami, May 3rd, 1907.

Dear Comrade And Fr1end.

Please forgive me for not writing to you for a long time. During last few months I was very busy, owing to the persecutions of the Government. Now that our daily has been suppressed and our many comrades have gone to the prison, I have no work, no business, so I got leisure to write. I am now alone, at an inn in Yugawara, a famous watering place, one day's ride from Tokio. I came here to improve my health and am now translating a pamphlet, Arnold Roller's "Social General Strike."

My book, in which are collected my essays on AntiMilitarism, Communism, and other Radicalism, has been prohibited and many copies seized by the Government, but the cunning publisher secretly sold 1,500 copies before the policemen came.

Mrs. Yamanouchi is living with her mother and grandmother in a country villa near Tokio. Her family is rich, but she is preparing to live an independent life. She says she does not like to live a parasite's life. I am now looking for her work. My wife and Magara Sakai were very pleased with the fine cards from you. Magara is now with her father. She is four years old and a very amiable child.

Have you seen the Japanese students in Berkeley who are publishing a magazine which caused a sensation last anuary? They are all clever and devoted libertarians.

hope the future revolution in Japan will be caused by their hands. Please teach them, educate them, instruct them.

Mr. Sakai is working on an "Encyclopedia of Social Problems" with a few young comrades. Its accomplishment will take five or six months after this. It will have great effect for the education of our people. I am going to translate Kropotkin's works.

I am very anxious to hear of your eyes. Eyes are very important organs for all men. Take care of yourself. Remember me to your daughter and granddaughter. I ever remain,

Yours fraternally,

D. Kotoku.

(To be Continued.)

ECONOMY AS VIEWED BY AN ANARCHIST

By C. L. James.

(Continuation.)

Anarchism is no patent scheme for introducing "the reign of the Prince of Peace." It does not ignore the bitter fruits of sin. It does not deny that personal ignorance and stupidity are the prime causes of all our sufferings. It does not imagine that man can be free and woman be a slave. It makes no Omnipotent Goodness out of a popularly elected legislature. But it does perceive that when men combined to enslave other men they first laid upon their own necks a yoke called Government, which it is pitiful to hear them beg their drivers will by some never clearly designated hocus-pocus convert into a defense; that it is the worse and not the better part of human nature which is organized for perpetuity by such combinations as States; that the spontaneous tendency of desire working in individuals is towards improvement; that the weight which forever drags us back into our old afflictions is Law, the petrified tradition of a barbarous past! Before proceeding to illustrate this through a brief review of economic history, observe that interest is the fruit of artificial monopoly just as much as rent. We may inquire whether anything can be done for its complete extinction when we have cleared away its factitious bulwarks—the chartered monopolies whose constantly accumulating Surplus Value makes them the fountain heads of usury; whose high profits on such illicit speculation as the Credit Mobilier renders possible the ravaging rate of loans;22 and whose traditional methods express themselves in conspiracies as much disapproved by the very government to which they owe their own existence as are those of the Standard Oil Company

22"The world's wealth hardly increases three per cent, a year. Three per cent, is reckoned a very low interest. Why does not Interest eat up the world? Because it is not paid! What becomes of it? Ask the ruined speculators after a financial "crisis."

21. It is remarkable how small a part of economic history can be rationalized from the premises of orthodox Economy; and how much light is cast upon true methods of generalization as soon as we begin seeking them among the facts! I suppose it is no longer imagined that man's primitive condition was anything else than the lowest state of savagery; but what that means is not quite easily made intelligible. Cannibalism is far from being the lowest state. It requires an amount of courage, energy, and aspiration, not possessed by the most degraded races of men, and accordingly does not seem to exist, certainly not on a large scale, among the negrittoes of Melanesia or Central Africa. They are mere grazers upon Land. But there is evidence that cannibalism did once prevail among the Negroes, Polynesians, Indians, Turanians, the Semitic and Aryan races. Occasionally, as among the Aztecs, it persists into somewhat advanced social states but, as a rule, it gives way to hunting, in countries where large animals (there were none in early Mexico) can be killed with the rude weapons of the savages. Progress from the grazing to the hunting state illustrates at every step the rujes that men seek to gratify their desires with the least exertion, and that their desires are enlarged by the increase of their powers, brought about, as yet, mainly through natural and sexual selection, but already in some degree effected by Invention, a sure mark of knowledge increased through experience. A great change takes place when men have discovered that some large animals, as the horse, the dog, the sheep, and the bovine kinds, can be domesticated. This is easier than the chase. Cannibalism, an occasional resort of hunting nomads, wholly ceases. There is now, for the first time, a considerable accumulation of wealth, in the form of W. P. W.— breeding cattle—which is also Capital, enabling the patriarch to obtain a Surplus Value from the labor of his sons, wives, slaves, naturalized aliens, and unlucky members of the horde. The subjection of women, the earliest among wrongs and the parent of all others, becomes a little mitigated. Even before that the young savage was required to prove himself fit for his father's trade of war before he could marry; but now something else becomes necessary, not through arbitrary regulation, but natural law. For the cattle-raising nomad to have a family is simply impossible until he has acquired stock enough for the support of one; while from the marriage contracts or settlements spring certain customary rights of dower and separation which are favorable to the weaker sex. Up to the cattle-raising stage, increase of population is slow. Except for requiring young men to show their proficiency in arms and endure the cruel rites of barbarian confirmation, there is, indeed, no Preventive or Prudential Check, but barbarians below the stage of cattle keeping are desperately poor, and their multiplication is continually checked by famine, pestilence, which they are too ignorant to combat; war, infanticide, cannibalism, and accidents of the chase. After they begin to keep cattle, these animals, propagating much faster than the men, enable men also to increase rapidly; nor have they learned any reason why they should not. The migratory patriarch of a horde whose members are all actual or adopted members of one family, measures his power by his posterity; he is a polygamist who buys or captures women whenever he can; his descendants quickly multiply, and, like all subjects, they imitate their king as much as they can, so that the rapidity with which a pair becomes a nation is often quite startling. But there is a limit to the possibility of such life. The cattle must be fed, as well as the people; so, when their numbers become too great for land, uncultivated and mostly poor, it becomes necessary that the tribe should divide or else decamp bodily. The emigrating portion either gets a better country or perishes in a great defeat, and the native pasture land of nomads remains as little improved as formerly. Agriculture, however, originates in regions especially favorable to the simpler kinds. Rice in India, dates through northern Africa, corn in the tropical belt of America, poi in the Sandwich Islands, etc., are so easily raised that a few nations, as the Aztecs and Polynesians, have attained some degree of agricultural proficiency without becoming masters of large laboring animals; but this is rare. In most cases, people have discontinued nomadism only after acquiring considerable knowledge of how to gather and thresh grain, weed fields, hoe, plow, harrow, etc., in aid of which operations they had cattle. Leisure and experience have diversified their desires, and it becomes easier to gratify them by the agricultural life than that of shepherds, which, accordingly, is left to the backward inhabitants of the poorest sections. The settled habits of agriculturists are very favorable to individualism, and in the same proportion opposed to the communism of savages. It is easy for grazers, cannibals and hunters to have almost all their scanty possessions in common. The maker of weapons cannot, indeed, live on his product, and therefore, since all want it, he must be paid for it. But he is a salaried functionary, paid, not by individuals, but the tribe; and the same is true of the weaver, potter, basket-maker, and what other workmen, excepting fighters and hunters, there are. In the stage of shepherd nomadism there is, indeed, as we saw, a great accumulation of what is at once W. P. W. and Capital. But almost all belongs to one person, who, moreover, holds it in a sort of trust, as the head and representative of the tribe. So conservative are barbarians that they do not give up the most inconvenient practises without shame and fear of offending the gods. Such institutions as the prytanaeum—the public hotel where officials during their term, foreign ambassadors, pensioners, and other guests of the community live free of cost to themselves—as the temple of Vesta, a reminiscence of the old village campfire, kept by revered and sacred characters, show how the forms of community life persist after the substance has passed away. A really serious matter, however, is that in many countries— India, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, etc.—land, though occupied and cultivated by individuals, continues to be the property of the people's Great Father, the king, to whom the heavy ground rent is paid. That this system would be a good one under a democratic government with socialistic maxims, as its advocates propose, may be possible, and may not be true. But there can be no question that where it actually exists it is a bad one. More defensible from the quasi-moral point is the reservation of common lands. But everywhere we can see that the tendency of agriculture towards individuality is too much for this ancient practise. Commons continue to be divided and enclosed, despite the Corn Law rhymer's well-known complaint; and this not because monopolizing landlords buy venal legislators, though this doubtless assists a deeper process; but because W. P. W. can get more out of the commons than the unsystematic work of those few poor people to whom the enclosure is a hardship.

(To be Continued.)

SOME BOOKS

By M. B.

THOSE who are entertained by tales of shipwreck, cannibalism, and combat may enjoy Jack London's story "Adventure."* The work is an attempt to portray adventure on the background of reality. In the old standard stories of similar nature we see the characters move about, attack, rob, and murder each other for no discoverable reason save that of serving as lay figures for the narrator. It is somewhat different with Jack London's story. His adventurers know what they are about: they want to live, gain wealth, win success. Even the heroine, Joan Lackland, who is introduced to us as an adventuress for adventure's sake, finally grows to dislike her holster and 38 calibre revolver. She marries and will apparently become a good business woman, unless her time be entirely occupied by a good-sized flock of children.

The story of "Adventure" is located in the South Sea Islands, the beche-de-mer region, the sometime sphere of the heroes of Edgar Allan Poe. There live savages, cannibals, bushmen. Compared with the latter, the savages and cannibals may be considered as gentle folk. Moreover, the bushmen are quite useless to the white man, since they refuse to be domesticated and cannot be persuaded to slave on the plantations under fake contracts. That, truly, is provoking, for the lords of the plantations are eager to play the role of civilizers. The savages on the coast, on the contrary, have already so far become amenable to civilization as to submit to slavery. Sometimes indeed they rebel; but the civilizers are quick to apply the whip or simply shoot them.

The happenings in "Adventure" are of a commercial rather than romantic nature. The reviewer, remembering "Martin Eden," can't help cursing the time that misleads a true artist into committing the mediocre.

* Macmillan Company, New York. $1.50.

In "The New Machiavelli"* H. G. Wells treats of illegitimate love and politics. Because of a love affair a man must sacrifice his political career: the Puritan swine grunt too loudly. Thus it happened to Charles Dilke, to Parnell, and many another.

Fortunately, the perusal of "The New Machiavelli does not make us feel that England or "humanity" is the loser by the termination of the hero's career. Of a real Machiavelli there is not even a trace in him: he is a thorough Fabian; that is, a hopeless experimentalist and aesthetic amateur.

The political constructive phase of the book is its weakest part. Wells rides his hobby with great perseverance. Thus the idea of the endowment of motherhood is mercilessly done to death. Well, let him! It has honestly earned the peace of the grave.

So far as details are concerned, however, the work is rich in splendid observations. Wells is always at his best when the politician in him is silenced and the artist allowed to speak. Then his humor shines out of bright eyes, looking upon the world understandingly.

The father of the hero suffered the misfortune of inheriting three old houses. They inspire him to the following remarks concerning the effect of property on the human soul:

"These damned houses have been the curse of my life. Stucco white elephants! Conferva and soot. . . . Property, they are! . . . Beware of things, Dick; beware of things! Before you know where you are, you are waiting on them and minding them. They'll eat your life up. Eat up your hours and your blood and energy! When those houses came to me, I ought to have sold them—or fled the country. I ought to have cleared out. Sarcophagi—eaters of men! Oh! the hours and days of work, the nights of anxiety those vile houses have cost me! The painting! It worked up my arms; it got all over me. I stank of it. It made me ill. It isn't living—it's minding— . . .

"Property's the curse of life. Property! Ugh! Look at this country, all cut up into silly little parallelograms; look at all those villas we passed just now, and those potato patches and that tarred shanty and the hedge! Somebody's minding every bit of it, like a dog tied to a cart's tail. Patching it and bothering about it. Bothering! Yapping at every passer-by. Look at that notice-board! One rotten, worried, little beast wants to keep us other rotten, little beasts off HIS patch—God knows why! Look at the weeds in it. Look at the mended fence! . . . Human souls buried under a cartload of blithering rubbish."

* Duffield & Co., New York.

Such paragraphs enable the reader patiently to glance over many pages, which, though enlarging the bulk of the book, do not enrich its contents.

"The Chasm,"* by George Cram Cook, is a story with a Social Democratic label and abortive class-consciousness. But for the missing recital of the great deeds which Victor Berger will not perform in Congress, the book is a good specimen of a second-rate Socialist editorial or pamphlet.

The Civic Federation should not ignore the valuable suggestion of Love as the soothsayer of the class conflict.

Mr. Theodore Schroeder has published a unique book,—unique both in point of contents and because it is not for sale. It is dedicated to the friends of liberty; its purpose, to serve their mission. But not only friends of liberty,—the psychologist, the ethnographer, the lawyer, and the judge will study the book with profit, unless they be blinded by prejudice.

The work of Mr. Schroeder, "Obscene Literature and Constitutional Law,"** contains a mine of valuable material. The moralist, eager to punish, can find neither place nor occasion where his contentions are not open

* Frederick A. Stokes Co., New York. $1.25.

** The book is unique, because it can not be bought by the laity. It is published by the Free Speech League, New York City. We hope to print a lengthy treatise on the book shortly. to challenge. The greatest confusion prevails among judges and officials of the Postal Department as to what is right or wrong: what one considers proper is condemned by another as highly immoral. But unfortunately the nosing about for obscenity is not merely ludicrous; it has seriously injured art and literature, and is frequently the cord to strangle free speech and press.

Were there in Congress a single man of courage and understanding, unafraid of the howling of the Pharisee mob, he would rise at the very first occasion to stamp the postal censorship with its right name and to unmask it as a disgusting mixture of stupidity and despotism.

This, too, is clarified by the book of Mr. Schroeder: the common law takes no cognizance of "obscene literature"; it is the judges and censorship which have dragged the thing into being, by the manufacture of precedents. Quite illuminating, therefore, is the saying of Sergeant Hill, quoted by Schroeder: "When judges are about to do an unjust act, they seek for a precedent in order to justify their conduct by the faults of others."

Now the censorship has become an institution. The question is how to abolish it. Mr. Schroeder's book is a most courageous attack upon the monster.

"The Man-Made World, or Our Androcentric Culture,"* by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, mirrors to Man the world as "he made it." Throughout history he has brutally domineered, fussed, waged war and exalted it. He has turned the home into the market-place of his violent instincts and lorded over it. He has degraded woman to a domestic animal and an object of lust. When he speaks of the human he always means the male; he impresses upon everything the alleged superiority of his near-sighted viewpoint.

Thus looks the picture reflected by the mirror of Mrs. Gilman, showing the rascality of our man-made world. I think, however, that the author does Man too much credit. The fellow has brought as little consciousness to the shaping of the world as did woman.

* Charlton Co., New York.

He is not its creator; in the majority of cases he is its mere creature. He lags behind with undecisive step, and generally the poor dunce wots not whither he goeth. His boastfulness, petty tyranny, and lack of consideration are acquired weapons in the wretched competition which is nowadays proudly termed the struggle for existence,—the struggle for bread and butter, more appropriately.

It must be noted, however, that woman, generally speaking, rather encourages than opposes these disagreeable traits of man,—which surely does not speak favorably of her taste.

In reality, were man the conscious creator of this world, he should be condemned without benefit of clergy. But until now the history of mankind appears as a brew of stupidity and narrow self-interest, for which both sexes have supplied the ingredients. Therefore they should work in common toward bringing into the world more beauty, sense, and justice. That women should equally participate in this better future is, for us, selfevident.

LITERATURE FOR CHILDREN

FOR some years part of my work was to select Sunday-school libraries, and quite often complaints would reach me from customers, to whom these selected libraries were sent, that such and such a book had been thrown out by their reading committee because dancing was mentioned and not condemned; or some story contained a child-christening scene which was not denominationally orthodox.

Some of the books condemned had everything to commend them from the standpoint of the prospective buyer, but unfortunately one of the characters used "Oh, Pshaw!" or "Darn It," or some other such profane, obscene or unchristian expression, and back came the book.

I can not help but think that some concerted action on the part of liberals in the way of selecting and suggesting readings for the very young would be a most commendable work, and to this end I should like to open correspondence with men and women who are interested in securing for radical homes a few books that are not forever harping on what God did, and how and why and when; how bad this or that awful man or woman was in the story because, forsooth, they went fishing on Sunday or said something disrespectful of some skypilot.

I do not think there are fifty books for young children (if nature stories be excepted) that are not dangerous to liberal ideas or whose insidious moralistic implications are not a refutation of the liberal teachings of well-read parents.

Let us produce a sane, unbiased, healthy literature for the little folks; stories in which unconsciously are woven Shakespeare's grand thoughts, such as "For there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so," and Swinburne's "All glory to Man in the Highest, for man is the master of things"; and that greatest of rebels, Jesus: "If a man work not neither shall he eat." Thoughts like these unobtrusively permeating children's stories—how much better than the sentimental slush found in "Little Eva" in Uncle Tom's Cabin; "The Story of Patsy"; "Bird's Xmas Carol," where so jesuitically the tender mind of the child is imbued with the glory of charity; the kindness of the good-rich; a feeling, if poor, of the need of ingratiating oneself with the rich; or, if rich, of caddishly patronizing the poor; the feeling of submission—of putting one's trust in the good lord who knows what is best for us. That is what the child of the radical reads! No wonder that real soul-liberalism is so very scarce; no wonder there are still so many moral bugaboos—so much of the spirit of dependence—so much respect for property— such grasping for riches. It is ground into us from babyhood. Our mental food is tainted. Let us read critically, from the standpoint of the radical, and compile a list of books that are at least not mentally poisonous.

Those who will help me do this most necessary work kindly address:

S. T. Hammersmark,

610 Third Avenue, Seattle, Wash.

INTERNATIONAL NOTES

THE present reaction in Japan plays havoc not merely with Socialists and Anarchists, but also with modern writers. Mr. Yone Noguchi, an author well known in America and England, writes in the London Academy regarding the terrible persecution of literary men in Japan:

"If there is a most unkind country for writers and literature, that is Japan—at least present Japan. Since the war, particularly in the last three years, the Japanese government has had two objects—namely, to stamp out Socialism and "naturalism," which, both of them, insist on perfect individualism. It seems to me that she used every possible power of the police and Press law toward her end; many writers were supposed, in fact, to be as dangerous morally and socially as Anarchists. The government set the police on them."

Mr. Noguchi also dispels the myth regarding Japanese patriotism:

"It is the work of superficial observers to see only the uniform of Japan's patriotism in the Russia-Japan War; it is quite right to say that it only overshadowed, with its astonishing glitter of ancient sword, the elements of Western individualism which at the time of that war had begun to make their existence clear. The new Japanese attempted to qualify the meaning of patriotism from another standpoint. Kotoku, who was hanged recently as the leader of the now famous treason case, and many others raised the anti-war cry; we have many an unpublished story of deserters who were at once courtmartialed. Some critics even deny the Japanese bravery which the Western mind associates with the war. It would surprise the Western readers if we told our own story, to be sure."

The writer concludes his interesting article with the following words of protest and admonition: "The time is changing, but I am not ready to prophesy what the result will be for the government who does not realize the Time's change, and even flatly denies its existence."

* * *

THE ignorance of the Crown Prosecutors of Prussia is a commonplace. A recent instance was given in the case of Der Freie Arbeiter, an Anarchist publication of Berlin. An issue of the paper containing an article entitled Die Neue Revolution, from the pen of Richard Wagner (originally published in 1849 m tne Sachsischen Volksblatter), was confiscated. The Crown Prosecutor, ignorant of the literature of his country and not dreaming that the author of the article was no other than the great Richard Wagner, caused the arrest and indictment of the editor of Der Freie Arbeiter, who, of course, was acquitted by the judge, to the great discomfiture of the prosecutor.

A similar incident proving the universality of authoritarian ignorance occurred in this country, but the jury of American peers proved as stupid as the German prosecutor. In 1901 John Most was indicted for an article published in the Freiheit. The author was Karl Heinzen and the article had originally appeared in The Pioneer about fifty years previously. Unlike the German judge, the American jury doomed Most to the penitentiary.

THE Prussian authorities continue to make themselves ridiculous. The editor of Der Freie Arbeiter, Comrade Becker, was found guilty of blasphemy because of the following quotation from Friedrich Nietzsche's "Antichrist": "I condemn Christianity. I bring against the Christian Church the most terrible indictment ever hurled against it by any accuser. The Church represents to me the worst of all conceivable corruptions. It ever willed to commit the very utmost of imaginable corruptions. The Christian Church has left nothing untouched by its ravages. Page upon page in its history bears witness to its bloodthirst, to the lowest passions of brutish stupidity and ferocity."

Thus the philosopher Nietzsche stands condemned, while the composer Wagner has been exonerated by the courts of Prussia.

* * *

The revolutionary movement in France has within a short period lost three of its most illustrious artists.

Shortly after the death of the writer Louis-Philippe, the illustrator Delannay passed away. And now the great singer of liberty, Gaston Coute, died. All three were ardent devotees to the cause of human emancipation with the inevitable result of constant persecution.

It was Delannay's imprisonment that was responsible for the fatal disease, while Coute was placed under indictment for one of his stories in La Guerre Sociale when on his deathbed.

Want was the life companion of these sons of the revolutionary muse; the hospital their last abode.

* * *

Two of the foremost veterans of the Anarchist movement are at present seriously ill: Peter Kropotkin in Switzerland, and Enrico Malatesta in London.

The persecution which Comrade Malatesta suffered in conection with the Houndsditch affair considerably aided in aggravating his conditon.

In connection with the illness of Comrade Kropotkin, the Swiss government came near committing a very serious crime against the sick thinker and writer. The Swiss press announces that the Federal Council has ruled that the expulsion order issued thirty years ago against Peter Kropotkin still holds good, and that it is only the fact that he is really ill that prevents his being deported and saves the Swiss government from committing an act of barbarity. As it is, the Federal Council has asked the Tessin government to report at once if Kropotkin should leave Minusio, where he is now, or Switzerland. Only the worst criminals are expelled from Switzerland for life; political expulsions are never for more than a limited time.

We hope that both of these our most beloved comrades will speedily recover, to devote many years to the service of the movement.

* * *

On the 19th of September the Italian Anarchists will open their Congress in Rome. It will be held in memory of Carlo Pisacane, one of the pioneers of the Anarchist movement. On the 20th a great memorial demonstration will take place.

The subjects to be discussed at the Congress are as follows: organization, propaganda, initiative, the press, the anti-religious and the anti-military movements, and the modern school.

* * *

Anatole France, ever the active opponent of injustice and oppression, has refused the cross of the Legion of Honor offered to him by the government of France. This refusal voices his protest against the persecution of radical artists and revolutionists.

Anatole France has by this action honored himself far more than could all the crosses of the Legion of Honor with which are decorated the bosoms of corruptionists and politicians.

* * *

Regardless of the numerous protests from various sources, three Russian revolutionists have been extradited to the autocracy by the Austrian police: Kravetz, Veronetzky, and Mikhalsky.

The authorities of Austria work hand in glove with those of Russia, and Russian revolutionists are to-day no safer in one country than in the other.

The Social Democracy of Austria has entirely sunk in the swamp of parliamentarism and totally ignores the fate of political refugees from other countries.

* * *

Comrade J. F. Fleming writes to us from Melbourne, Australia:

Dear Comrade:—I received the Manifesto to the Workers of the World, also Regeneration. I have sent a copy to the Trades Hall Council, and the Socialist Party. The Council is a semi-capitalist party, the delegates principal endeavor is to obtain a parliamentary job; as a matter of principle they always denounce revolutionary propaganda; therefore little will be gained from them. With regard to the Socialists, they are the same the world over; I need say nothing further. Should, by accident, any favorable development take place, I will inform you.

The military conscription has just commenced; in Yarrivelle, a suburb of Melbourne, the boys stoned their officers and compelled them to seek shelter in the rich men's houses. Militarism is very unpopular in Australia.

NOTICE

Though we are very reluctant to drop anyone from our lists, MOTHER EARTH cannot carry unpaid subscribers, since, even at best, it is published at a loss. Therefore we strongly urge our readers to send their subscriptions in AT ONCE.

Every renewal received during September and October will earn for the sender a free copy of "The Soul of Man Under Socialism," by Oscar Wilde.

If we do not hear from our unpaid subscribers during this month, we will have to take them off our list.

WHO ARE THE QUACKS?

A controversy between two doctors—Dr. W. J. Robinson, editor "Critic and Guide," and Dr. It. Liber, editor "Unscr Gesund."

The truth about the "regular" medical profession. Illustrated.

Very interesting for laymen and physicians of all medical schools.

An Important suggestion at the end of the book.

Price, 15 cents; to be sent to the publisher. B. Liber, M.D., 230 East 10th Street, New York City.

|