|

MOTHER EARTH

Monthly Magazine Devoted to Social Science and Literature

Published every 15th of the Month

EMMA GOLDMAN. Proprietor, 55 West 28th street, New York, N. Y.

Entered as second class matter April 9, 1906, at the post office at New York, N. Y. under the Act of Congress of March 3, 1879

VOL VII DECEMBER, 1912 No. 10

TO THE GENERATION KNOCKING AT THE DOOR

BREAK—break it open; let the knocker rust;

Consider no "shalt not," nor no man's "must";

And, being entered, promptly take the lead,

Setting aside tradition, custom, creed;

Nor watch the balance of the huckster'sbeam;

Declare your hardest thought, your proudest dream;

Await no summons; laugh at all rebuff;

High hearts and you are destiny enough.

The mystery and the power enshrined in you

Are old as time and as the moment new;

And none but you can tell what part you play,

Nor can you tell until you make assay,

For this alone, this always, will succeed,

The miracle and magic of the deed.

—John Davidson.

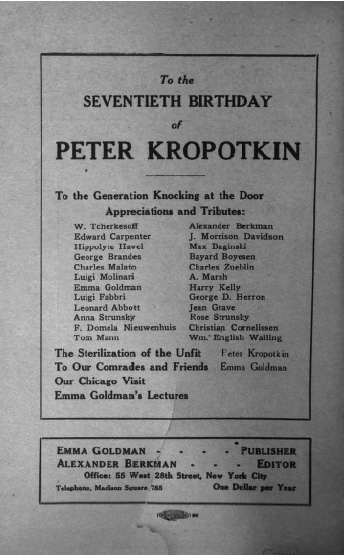

APPRECIATIONS AND TRIBUTES

OUR BELOVED COMRADE AND TEACHER

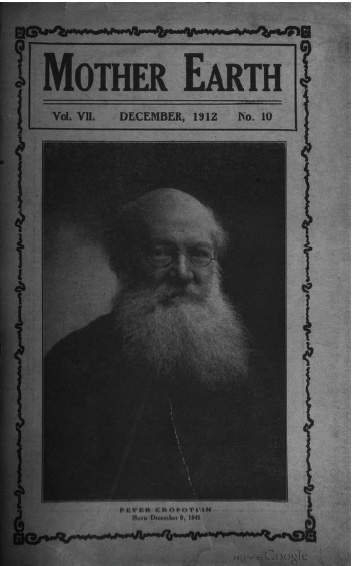

ALL over the world our Anarchist comrades have decided to celebrate the seventieth birthday of their beloved comrade and teacher Peter Kropotkin. If among the living authors and Socialists somebody deserves such a general demonstration of veneration and love, it is certainly Kropotkin, one of the greatest characters of our generation and the real glory of his native land, Russia.

In my long life as Socialist and revolutionist, I have had the chance to meet many gifted and exceptional people, excelling in knowledge or talent, and distinguished by greatness of character. I knew even heroic men and women, as well as people with the stamp of genius. . . . But Kropotkin stands as a most conspicuous, strongly defined character even in that gallery of noble fighters for humanitarian ideals and intellectual liberation.

Kropotkin possesses in delightful harmony the qualities of a true inductive scientist and evolutionary philosopher with the greatness of a Socialist thinker and fighter, inspired by the highest ideals of social justice. At the same time by his temperament he is undoubtedly one of the most ardent and fearless propagandists of the social revolution and of the complete emancipation of working humanity through its own initiative and efforts. And all these qualities are united in Kropotkin so closely and intimately that one cannot separate Kropotkin, the scientist, from Kropotkin, the Socialist and revolutionist..

As scientist—geographer and geologist—Kropotkin is famed for his theory of the formation of mountain chains and high plateaux, a theory now proved and accepted by science, and, in recognition of which the mountains in East Siberia explored by him have been named Kropotkin mountains.

As naturalist and inductive thinker on evolution, Kropotkin has earned undying glory and admiration by his "Mutual Aid," a work showing his vast knowledge as a naturalist and sociologist.

One of the most striking works of Kropotkin, I may say even classical by its form, deep knowledge, brilliant argumentation and noble purpose, is his "Fields, Factories and Workshops." Here he shows to toiling humanity with facts and figur.es the abundance of produce obtainable, the comforts and pleasures of life possible if physical and intellectual work are combined, if agriculture and industry are going hand in hand. I think that for the last quarter of a century no book has appeared so invigorating, so encouraging and convincing to those who work for a happier society. No wonder that a London democratic weekly advised its readers to buy his book by all means, even if they had to pawn their last shirt to raise the shilling.

Kropotkin as a Socialist, as a Communist-Anarchist and revolutionist, . . . but who of our readers does not know his numerous and inimitable writings on Socialism, on Anarchism-Communism, etc.? Who has not read and enjoyed his "Memoirs of a Revolutionist"? His "Paroles d'un Revolté," his "Conquest of Bread," "Modern Science and Anarchism," "Russian Literature," "The Terror in Russia," "The State and Its Historic R&ocap;le," etc., etc. Here I will not dwell on those books; I have another aim in this article.

I will attempt to give an idea of the personal character, the charming individuality of. the author of all those splendid books. First of all let me try to sketch Kropotkin at work.

I often ask myself if there exists another man equal to Kropotkin in quickness, intensity, punctuality and variety of work? It is simply amazing what he is capable of doing in a single day. He reads incredibly much, in English, French, German and Russian; with minute interest he follows political and social events, science and literature, and especially the Anarchist movement in the whole world. His study, with its booklined walls, has piles of papers, new books, etc., on the floor, tables and chairs. And all this material, if not read, is at least looked through, annotated, often parts are cut out, classi fied and put away in boxes and portfolios made by himself. Kropotkin used to occupy himself for recreation with carpentry and bookbinding, but now confines himself to the latter and to the making of cardboard boxes for his notes. Whatever he does, he does quickly, with great exactitude; his notes and extracts are made with the speed of a stenographer, and all his work is done with beautiful neatness and correctness.

To give an idea of the variety of his work, I shall describe my last visit to Kropotkin. I came with a French scientist, also a great worker and a sincere admirer of Kropotkin. We found him in his study, hard at work, giving the last touches to a new edition of his "Fields, Factories and Workshops." One side of his table was covered with the French proofs of "La Science moderne et L'Anarchie." There were also the appendix and glossary in English for the coming Freedom edition of the same book. On a small table a half-finished article on Syndicalism was lying, and a pile of letters, some of them twelve pages long, exchanged with an old friend and comrade of the Federation Jurassienne, and dealing with the origin of Syndicalism, awaited an answer. Newspapers, books everywhere, volumes and separate articles on Bakunin were about, as Kropotkin is at present editing a complete Russian edition of Bakunin's works. In the midst of all these things, vigorous, alive, active as a young man, smiling heartily, Kropotkin himself. And people try to convince us that he is old and must rest I "Nonsense," said my French friend, "this is not an old and tired man; he is more alive now than many a young man of our present generation!" And really with his overflowing activity and spirits, he animates the whole household.

It is of course only natural that a man of his learning and all-sided development is much sought after. Specialists and scientists, political and literary people, painters and musicians, and especially Socialist and Anarchist comrades and Russian revolutionists, are visitors to his house, and charmed by his straightforward simplicity and wholehearted interest. Even children are at once captivated not only by his fatherly goodness, but by his capacity to share their enjoyment, by playing for and with them, arousing their delighted amazement by his juggling tricks and performances.

At the end of the day, when the household has gone to rest, Kropotkin, with his usual consideration for those who have worked, moves about the house like a mouse, tiptoeing so, as not to disturb the sleep even if only the servant has gone to bed. Often he has whispered to me to be careful so as not to awaken her. Lighting his candle, he retires to his own room, sometimes till midnight reading new publications for which he could not find time during the day.

It is not astonishing that all who conic in contact with him love and adore him.

But there is another side to his character. Kropotkin, the political and social thinker, the revolutionist, the Anarchist-Communist, with his fiery temperament of a fighter, with his inflexible principles, his insight in political and social problems, is yet more admirable; he sees further, he understands better, he formulates clearer than any of our contemporaries. Few people feel so deeply and acutely the suffering and injustice of others, and he cannot rest until he has done all in his power to protect and help. From 1881, when he was expelled from Switzerland for having organized a meeting protesting against the execution of Sophia Perovskaya and her comrades, up till recently when he feverishly wrote his "Terror in Russia," that crushing act of accusation against the Czar's wholesale murder and torture, he has always been the indefatigable defender of all the victims of social and political injustice.

Such is, in a few lines, Kropotkin, the Anarchist, the scientist, and above all the man, beloved by his comrades and friends, respected and admired by honest people the world over.

W. TCHERKESOFF.

* * *

IT IS with the greatest pleasure that I send a few lines to help in the commemoration of our friend Kropotkin's seventieth birthday. His work will be remembered for all time; for by it he has brought so much nearer the day when the true human society will be realized on earth—that spontaneous, voluntary, non-governmental society whose germ was first planted ages ago among nearly all primitive peoples, but whose glorious flower and fulfillment awaits us—and perhaps not so very far distant in the future—as the goal of our free, rational and conscious endeavor.

May he long live—and you also—to assist in the great work!

Fraternally and heartily yours,

EDW. CARPENTER.

KROPOTKIN THE REVOLUTIONIST

By HIPPOLYTE HAVEL

Of the thousands of congratulations and good wishes conveyed to-day to Peter Kropotkin by his admirers, friends and sympathizers, none will, I am sure, find in his heart such a responsive echo as those expressed—most of them in silence—by the simple workers in the Anarchist movement, the men who are neither writers nor speakers, whose names are unknown to the great public, the quiet, self-sacrificing comrades with out whom there would be no movement. Those of US who have shared their bed and their last bit of bread know their feeling for the beloved teacher, their love for the man who gave up his position among the favored ones and stepped down to the lowly to share their daily struggle, their sorrows, their aspirations; the man who became their guide in the sacred cause of the Social Revolution.

Many wil1 speak of Kropotkin as the great natural scientist, the historian, the philologue, the littérateur; he is all this, but he is at the same time far more—he is an active revolutionist! He is not satisfied, like so many scientists, merely to investigate natural phenomena and make deductions which ought to be of value to mankind; he knows that such discoveries cannot be applied as long as the system of exploitation exists, and he therefore works with all his power for the Social Revolution which shall abolish exploitation.

Were it not for men like Kropotkin, the pseudo-scientific Socialists would long since have succeeded in extinguishing the revolutionary flame in the hearts of the workers. It is to his lasting credit that he has used all his great knowledge to fight the demoralizing activities of these reformers, who use the name of Revolutionist to hide their mental corruption. It is this—the uncompromising attitude, his direct participation in social revolt, his firm belief in the proletariat—which distinguishes Peter Kropotkin from many other leaders of modern thought. He is the most widely read revolutionary author; the Bible and the "Communist Manifesto" are the only works which have been translated into 50 many tongues as "The Words of a Rebel," "The Appeal to the Young," and other writings of Kropotkin. It would be impossible to state in how many editions and translations each of his pamphlets has appeared. Some times I wonder whether he would recognize his own children: the pamphlets go through so many transformations in their journeyings from one language to another!

Peter Kropotkin is the most beloved comrade in the Anarchist movement; his name is a household word in the revolutionary family in all parts of the world. Our ill-fated Japanese comrades were proud of being called Kropotkinists. This was no idolatry on their part, but simply the expression of deep appreciation of his work. Those who have had the opportunity of meeting Kropotkin in his home or in public know that simplicity and modesty are his chief characteristics. As he never fails to emphasize that our place is among the workers in the factories and in the fields, not among the so-called intellectuals, so is he never happier than when he sits with his comrades and fellow-workers. I remember his indignation several years ago in Chicago when he accepted an invitation to a social gathering, expecting to meet his comrades, and found himself instead among vulgar bourgeois women who pestered him for his autograph. The irony of it! The man who gave up gladly his position at the Russian court to go to the people being entertained by the porkocracy of Chicago!

One of the bitterest disappointments of his life, as he himself told me, was that he could not participate actively in the great Russian Revolution. His friends and comrades decided that he could render the revolution far greater aid if he remained in London as one of the organizers of the gigantic struggle. But what arguments they had to use to convince him!

Peter Kropotkin's life and activities demolish the shallow arguments of our utilitarians, who judge all spiritual and intellectual life from their own narrow point of view. His work disproves the belief that ours is an age of specialists only. Like every great thinker, Kropotkin is many-sided in his intellectual activity; life and science as well as art find in him a great interpreter.

Looking back over the seventy years of his life, he must needs feel gratified with his work. The Anarchist brotherhood, to which he belongs, rejoices with him today.

* * *

PETER KROPOTKIN

HE IS the man of whose friendship I am proud. I know no man whose disinterestedness is so great, no one who possesses such a store of varied knowledge, and no one whose love of mankind is up to the standard of his.

He has the genius of the heart, and where his originality is greatest, as in "Mutual Aid," it is his heart which has guided his intellect.

The passion for liberty which is quenched in other men, when they have attained the liberty they wanted for themselves, is inextinguishable in his breast.

His confidence in men gives evidence of the nobility of his soul, even if he had perhaps given the work of his life a firmer foundation, having received a deeper impression of the slowness of evolution.

But it is impossible not to admire him when1 we see him preserving his enthusiasm in spite of bitter experience and numerous deceptions.

A character like his is an inspiration and an example.

GEORGE BRANDES.

* * *

A MAN

IT IS a great joy for those who love Kropotkin to participate in the homage—merited, indeed—which is being rendered to him to-day.

Whether on the occasion of his seventieth birthday or on any other occasion we have the right, without fear of being accused of hero-worship, to proclaim that we are proud and happy to have for a companion in thought and in the active struggle, for an elder brother and a respected leader the man who wrote "The Words of a Rebel,"

All movements either of ideas or of deeds which stir society to its very foundations naturally throw to the surface elements utterly opposed one to the other—the arriviste and the apostle; the man without conscience, who discredits in the eyes of the people whom he uses for his private ends those theories which he preaches, and the disinterested and impartial thinker who consecrates his life to the Ideal.

Peter Kropotkin is one of those who has commanded the admiration and esteem of his enemies themselves. The man, the revolutionist, and the scientist formed in him a complete unity, a living antithesis to those individuals with great intellect and feeble heart who might well take for their motto: Do as I say, not as I do. With him the same pure flame illumines the mind, warms the heart, and guides the conscience.

Born in the country which has remained the most absolutistic in Europe, Kropotkin became disgusted with all inequalities and barbarisms, and voluntarily renounced the very things for which other men strive with all their strength—wealth and the vain baubles of worldly position. But the mystic communism and Christian resignation of a Tolstoi did not appeal to him. Inspired by the influence of the Great Revolution, which scattered afar the germs of new ideas, and not by the old evangelists prattling of a puerile humanitarianism, Kropotkin became one of those who conspired against the odious régime of the Czar.

Scarcely had he escaped from Russian prisons before he was imprisoned anew. In France, whither he had come to continue the great social struggle which has for its battlefield the entire world—in the land of the Rights of Man new trials awaited him. The bourgeois republic, in reality the slightly veiled despotism of politicians and capitalists, apprehended him: Kropotkin was imprisoned at Clairvaux, and came forth with his great book, "The Words of a Rebel," in which his whole soul palpitates.

Monarchical England proved more hospitable to him than republican France. Remote from the tumultuous continental groups, but in touch with the world-wide movement of ideas, Kropotkin in an uninterrupted succession of articles and of books, rounded out by his lectures, has crystalized the great human tendency toward Anarchy and affirmed the necessity for a new morality opposed to the pharasaical morality of bourgeois society. In "The Conquest of Bread," followed by "Mutual Aid" and "The Great French Revolution," he sets forth with luminous clarity the goal of the struggle: liberty and well-being for all; the ideal which, more or less imperfectly visioned, has been the aspiration of revolutionists of all ages.

One might well believe that his broad sympathies help to deceive him as to the innate force of the people by ascribing to them the energy and clearsightedness which he himself possesses, but the lines which he has written regarding the r&ocap;le of the revolutionary minorities demonstrate that his intellectual vision is not subservient to his humanitarian sensibilities. And the lecture, printed in pamphlet form, which he delivered on "The Place of Anarchy in Socialistic Evolution" testifies perhaps more forcefully than a large volume his wide knowledge of the laws governing social phenomena.

In our time, when the capitalist world is sinking into decadence and the proletarian is not yet entirely released from the swaddling clothes of ignorance and superstition; when parasitical renegades, ambitious and unscrupulous, seek under the cover of Anarchy to satisfy their bourgeois desires, it is encouraging to meet—and to salute—such a man as Kropotkin.

CHARLES MALATO.

* * *

WITH my whole heart I join with you in paying honor to our Comrade Peter Kropotkin. The libertarians of Italy owe him a great debt, and we all love him as our intellectual father. His life of labor and sacrifice for humanity is a potent example and a great inspiration to all in whom burns the fire of liberty and emancipation.

Fraternally,

LUIGI MOLINARI

PETER KROPOTKIN

By Emma Goldman

THOSE who constantly prate of conditions as the omnipotent factor in determining character and shaping ideas, will find it very difficult to explain the personality and spirit of our Comrade Peter Kropotkin.

Born of a serf-owning family and reared in the atmosphere of serfdom all about him, the life of Peter Kropotkin and his revolutionary activity for almost fifty years stand a living proof against the shallow contention of the superior potency of conditions over the latent force in man to map out his own course in life. And that force in our comrade is his revolutionary spirit, so elemental, so impelling that it permeated his whole being and gave new meaning and color to his entire life.

It was this all-absorbing revolutionary fire that burned away the barriers that separated Kropotkin, the aristocrat, from the common people, and flamed a clear vision all through his life. It filled him, the child of luxury, of refinement, the heir of a brilliant career, with but one ideal, one purpose in life- the liberation of the human race from serfdom, from all physical as well as spiritual serfdom. How faithfully he has pursued that course, on? Those can appreciate who know the life and work of Peter Kropotkin.

How faithfully he has pursued that course, only those can appreciate who know the life and work of Peter Kropotkin. Another very striking feature characteristic of this man is that he, of all revolutionists, should have the deepest faith in the people, in their innate possibilities to reconstruct society in harmony with their needs.

Indeed, the workers and the peasants are, to Kropotkin, the ones to hand down the spirit of resistance, of insurrection, to posterity. They, unsophisticated and untampered by artificiality, have always instinctively resented oppression and tyranny.

With Nietzsche, our comrade has continually emphasized that wherever the people have retained their integrity and simplicity, they have always hated organized authority as the most ruthless and barbaric institution among men.

Possibly Kropotkin's faith in the people springs from his own simplicity of soul-a simplicity which is the dominant factor of his whole make-up. It is because of this, even more than because of his powerful mentality, that Revolution, to Peter Kropotkin, signifies the inevitable sociologic impetus to all life, all change, all growth. Even as Anarchism, to him, means not a mere theory, a school, or a tendency, but the eternal yearning, the reaching out of man for liberty, fellowship, and expansion.

Possibly this may also explain the truly human attitude of Peter Kropotkin toward the Attentäter. Never once in all his revolutionary career has our comrade passed judgment on those whom most so-called revolutionists ha only too willingly shaken off-partly because of ignorance, and partly because of cowardice-those who had committed political acts of violence.

Peter Kropotkin knew that it is generally the most sensitive and sympathetic personality that smarts most under our social injustice and tyranny, personalities who find in the act the only liberating outlet for their harassed soul, who must cry out, even at the expense of their own lives, against the apathy and indifference in the face of our social crimes and wrongs. More than most revolutionists, Peter Kropotkin feels deeply with the spiritual hunger of the Attentäter, which culminates in the individual act and which is but the forerunner of collective insurrection-the spark that heralds a new Dawn.

But Peter Kropotkin does more. He also feels with the social pariah, with him who through hunger, drudgery, and lack of joy strikes down one of the class responsible for the horror and despair of the pariah's life. This was particularly demonstrated in the case of Luccheni, who was denounced and denied by nearly all other radicals. Yet no one can possibly have s an abhorence of violence and destruction of life, as our Comrade Peter Kropotkin; nor yet be so tender and sympathetic to all pain and suffering. Only that he is too universal, too big a nature to indulge in shallow moral censorship of violence at the bottom, knowing- as he does- that it is but a reflex of organized, systematic, legal violence on top.

Thus stands Peter Kropotkin before the world at the age of seventy: the most uncompromising enemy of all social injustice; the deepest and tenderest friend of oppressed and outraged mankind; old in years, yet aglow with the eternal spirit of youth and the undying faith in the final triumph of liberty and equality.

* * *

OUR DEBT TO KROPOTKIN

We Anarchists, whatever our particular interpretation of radical doctrines, we are the heirs of Peter Kropotkin, and we are all inspired by a strong sense of gratitude, or affection and admiration. It is because of his labors that Anarchism won the "right of citizenship" among modern sciences and philosophies- we owe it chiefly to him, and we say this without the least wish to disparage the great services to the cause_ of liberty given by our other comrades the world over.

Especially do we love and admire our Comrade Peter, because he has most unselfishly devoted his whole life to the cause of human emancipation. He has given his great talents and all his wonderful energy to the service of the proletariat: his poverty is his greatest crown. He could have been one of the powerful of the earth, one of the privileged of the bourgeoisie. He preferred to cast in his lot with the oppressed and disinherited, preferred to be persecuted and imprisoned, rather than to be "the darling of the great." His vast learning and all the power of his intellect he has consecrated to the common people, and he has proved the greatest thinker and propagandist of Anarchism.

Pardon these words if they seem like adulation. They are the spontaneous expression of our deep love for our great teacher and comrade, to whom; the Anarchists of the world to-day send their heartfelt greetings, in the hope that he may be preserved to us for many long years, to continue the great struggle for progress and liberty.

When we speak with our political opponents, it requires but a few words to convince oneself that even an bitterest among them speak in admiration of our good Comrade. It is with a sense of justified pride that we say to them and to ourselves, "He is one of us!"

Luigi Fabbri.

Crespellano, Italy, November, 1912.

AN INTELLECTUAL GIANT

By Leonard Abbott

Every great cause has its heroic exponents and leader. Anarchism is fortunate in being able to put forward as its standard-bearer so great a man as Peter Kropotkin. I have before me as I write, some of the books and pamphlets of which he is the author. They make a formidable showing and range all the way from the pure science of "Mutual Aid" and the pure literature of "Russian Literature" to the revolutionary doctrine of "Expropriation" and "An Appeal to the Young." As a kind of introduction to the shelf-full of books, I recommend Victor Robinson's glowing and eloquent tribute, "Comrade Kropotkin."* In it the reader will find perspective and background.

Kropotkin's intellectual output for many years has been of a quality that compelled respect even from his bitterest opponents. His unction, it would seem, has been in part to cover ground that otherwise might have been neglected. His erudition is enormous; is style warm and sincere.

Nothing in radical autobiography excels the "Memoirs of a Revolutionist." Who that has -read Kropotkin's account of his first imprisonment and escape can ever forget it? Here are the very throb and passion and romance of the revolutionary struggle as it has gone forward in Russia during the past half century. "The Great French Revolution," which Francisco Ferrer was planning to publish in Spanish just before he was arrested and executed, is an almost equally notable achievement in the historical field. Conceived in something the same spirit as the "History of the French Revolution," By C. L. James, the American Anarchist, it aims to emphasize the great part played in the Revolution by the people of the lower stratum. Kropotkin points out that the historians of the period have very largely overlooked or neglected this phase of the struggle.

"Mutual Aid, A Factor of Evolution" has already become a classic in its field. It appeared as a kind of

_______________________

* Published by The Altrurians, I2 Mount Morris Park West, New York City.

sequel to Charles Darwin's "Descent of Man," and shows how cooperation, no less than individual struggle, plays its part in the biological process known as "the survival of the fittest." Huxley is said to have changed his views as the result of evidence presented in this work. Kropotkin's arguments have been discussed in all countries. They apply to human society no less than to the animals. They appeal to Socialists as well as to Anarchists.

"The Conquest of Bread" and "Fields, Factories and Workshops" are Kropotkin's two most important books in the domain of economic theory. They offer a clear definition of the Anarchist-Communist program. Especially timely and noteworthy at the present moment are his chapters on the decentralization of industries. In America, at least, the industrial tide runs overwhelmingly in the direction of trusts and unwieldy aggregations. This tendency has apparently not even yet reached its zenith. Socialism and governmentalism will gain from it. But a reaction' is sure to set in.

Kropotkin carries his learning lightly, and one feels behind his work a great heart as well as a great mind. When I met and talked with him in England fifteen years ago, I was struck by his sheer humanity and his beautiful courtesy. I came to him as a stranger, but he gave me several hours of his time. He talked of English trade-unions and the cooperative movement, of Belgian work ers, of French peasant-proprietors, and of Russian serfs. He spoke of the history and first beginnings of English Socialism; of Robert Owen arid Saint-Simon; of Karl Marx and Michael Bakunine and "The International." He gave his idea of the Paris Commune of 1871.

When I asked him if he thought we should go through Social Democracy to Anarchism, he grew vehement. "I hope not," he said; "I believe not. I should consider Social Democracy retrogression, not progress."

"The atmosphere of politics," he continued, "is enervating and corrupting. Look at the men who have gone Into our English Parliament, firmly resolved to fight for the workers against class tyranny; remember how many have been captured by the enemy. Our agitators—the Keir Hardies, Tom Manns and Ben Tilletts—are doing ten times as much good out of Parliament as they could do inside it. We must work out our salvation without the help of Parliament."

He paid a high tribute to William Morris, and I asked his opinion of "News from Nowhere." He replied: "It is an exquisite prose idyll, and is pure Anarchism in conception, but I can hardly conceive of society developing in just that way. There is a poetry of industrial mechanism, of machinery, that Morris never realized."

Brandes has written: "There are at this moment only two great Russians who think for the Russian people, and whose thoughts belong to mankind—Leo Tolstoy and Peter Kropotkin." I asked Kropotkin how he viewed Tolstoy. He answered in effect: "I admire his literary genius and his great spirit. But I am not in sympathy with his asceticism, nor with his doctrine of non-resist ance to cvii, nor with his New Testament literalism."

As I think of Kropotkin now, this conversation of fifteen years ago, in the little room at Bromley, comes vividly back to me. Since 1897 he has been twice in New York and has addressed audiences here. He seems to me to-day greater than ever before.

Hail to Kropotkin—Anarchist Prince, distinguished scientist, literary critic—on his seventieth birthday! The whole world is in debt to him, and his name and fame will spread over land and sea as the ideas he has pio neered are gradually understood and realized.

* * *

THREE CONTACTS WITH PETER KROPOTKIN

TOGETHER with all Socialists of my generation there was never a time when I did not know Kropotkin and was not inspired by his person ality, his revolutionary activity and the magnitude of his work as a scientist, thinker and propagandist. On three occasions of my life, however, I came in close, memorable contact with him. The first time was years ago at an ordinary Socialist meeting in San Francisco, when a youth mounted a platform and read the "Appeal to the Young." Is it a far cry from Russia to America, from the period of i&5o to that of a decade ago, from the Bastile of Saint Peter and Saint Paul to free California? Timeless and ageless is a revolutionist, and that evening Kropotkin was with us as actually as though we were one of his conspirative workingmen's audiences way back in his wonderful youth.

Stirring, invincible, absolute were his words as they reached us through the youthful reader on the platform. Thousands and hundreds of thousands had read that pamphlet and had responded to it as to nothing else in the literature of revolutionary Socialism, but more eloquent than the pamphlet was our thought of its author. Kropotkin wrote it, that Titan of the Russian and In ternational Revolution, that transitional character, bred of the misery of the Past, and carrying in himself all the glories of love and strength and beauty and freedom of the Future!

In that meeting years ago, as doubtless in countless others the world over, the thought of Peter Kropotkin dwelt like a Presence, and as ever and always, despite his greatness, he was simply our comrade, showing us, rather than telling us, how to conduct ourselves as revolutionists on the battlefield which is our life.

The second time I came in contact with him was when his "Memoirs" were published, that story of his years which is at once the story of the movement, wholly intertwined and inseparable one from the other. This book was an event to all who stood in the shadow of the Cause, and inspiration, a message, a personal gift. There was a new light in the atmosphere. It was as if a wind swept through the arid land. We became lighthearted, smiled, congratulated one another. Again it was the writer behind the written word that held us, it was the great heart, the transcendant mind, resolute, determined upon liberty, the large character nourished by the air and the soil of the Future, but warring passionately, indomitably with the Present.

Then came my third contact with him, actual this time. I remember the English fog, the one light ahead, which led to his house, then the warmth of his hand, and the embrace of his look, as he met me at the door on which I knocked. There stood a Ulysses of the Social Revolution, so vital, so inspired, so aglow with thought and feeling, that all my heart loved him, and I saw him through tears.

ANNA STRUNSKY.

OUR PETER

WHEN we speak among Anarchists of "Our Peter" (notre Pierre), everyone knows to whom we refer.

It proves the great popularity of our Kropotkin, whose seventieth birthday we are now celebrating.

It is not lip-service, but from the very depths of our hearts, when we say that we owe a great debt to Kropotkin, the man who has devoted his whole life to the propaganda of his principles. He who could be a rich man, he chose a life of struggle and hardship; lie who could wield power and have high rank, he preferred to lead the life of study and be an author for the people. His name reaches far, but his influence reaches still further. He will go down in the history of civilization as one of the pioneers of progress; he will occupy a permanent place in the book of human martyrdom for the emancipation of the working class from the yoke of capitalism.

We are not worshipers of saints, but we pay homage to him whose life is worthy to be honored. He belongs to us, and we are proud of such a man, a man whose profound knowledge, unexcelled integrity and high ideal ism have found appreciation even among his opponents.

Future generations will appreciate our comrade Peter Kropotkin at his full worth. But for us it is to give him what little token we may of our love, understanding, and esteem. And it is not for him that we do it: he needs not our praises; rather do we do it for ourselves. We feel happy that we can say to him, to the whole world, that we are proud of him.

Does that signify that we agree with everything he has written? By no means. Nor would he himself wish us merely to subscribe to his opinions. Such disciples would find small favor with him. He, most of all, wants thinking, self-conscious men and women. And it is as independently thinking men and women that we offer him our love and our gratitude.

With his life and his works he has wrought not for a day, but for all times His name will live as one of the best of his kind.

F. DOMELA NIEUWENHUIS.

Holland, November, 1912.

IN APPRECIATION

IN THE name of the Syndicalists in Britain I wish to join in loving greetings, most hearty congratulations and genuine thanks to Comrade Peter Kropotkin on his seventieth birthday. We heartily congratulate him on his full and intensely useful life; we thank him most sincerely for the battles he has fought, the struggles he has endured, and the example he has set.

It is more than twenty years since I first had the pleasure of meeting the great teacher; it is near thirty years since, as a propagandist, I joyfully began selling Kropotkin's "Appeal to the Young," one of the finest appeals ever issued in propagandist literature to young or old.

I have always felt it to be a great privilege to shake hands with and to have a few words with the grand old man, truly a delightful character. I have ever felt towards Comrade Kropotkin that there is an atmosphere of knowledge, of love, and of human kindness of heart surrounding him beyond that of any other man I have known.

So real a master of the knowledge of the time, so diligent a student of that yet to be known, and bearing himself withal so quietly, so unassertive, so superbly balanced, that I gaze on his modest, smiling, fatherly face in his photograph with wondering admiration.

That fate should have decided that our comrade should have lived in this country so long is a matter for us to be thankful for, but the mass of the working class have hitherto failed to learn one of the principal lessons the old teacher has been striving to inpart, i. e., the absurdity, the wrongfulness and economic unsoundness of relying upon State Action to bring about the economic changes essential for well-being: but the workers are learning that great lesson now and very rapidly.

In their struggle for the "Conquest of Bread" they will in future rely upon their own powers of Direct Action to achieve the same; and we are hopeful we shall yet be able to equal the barbarians of centuries ago in showing mutual regard for the general welfare.

I never read a more encouraging book than "Mutual Aid," and I thank our comrade for it; so full of delightful incident bearing so pointedly upon the all-important principle he is teaching, and so optimistic of humanity again being at least as sensible as the savages, coupled with scientific advance.

Many thousands have had their minds opened to the reception of knowledge by "Fields, Factories, Workshops," and many of us are strenuously engaged in endeavoring to apply the lessons therein taught.

We thank the Russian people for so glorious a man, and we thank the man and brother for such stupendous work so magnificently achieved. With our comrades of Europe, of America, aye, and of the world at large, we join wholeheartedly and offer our loving appreciation to Peter and Madame. May they have many happy years to observe the realization of their ideals.

TOM MANN.

Southflelds, London, Eng.

* * *

LOOKING BACKWARD AND FORWARD

AT THE thought of Kropotkin my mind reverts to the time when I was a little boy, the son of a middle-class family. The terms Socialist and Anarchist were quite unknown to me then, but "Nihilist" held a mysterious charm, swaying me with awe and admiration. It was a forbidden word and it conjured up visions of dreaded gendarmes, iron chains, and the frozen steppes of Siberia. Vaguely I felt that these forbidden people, the Nihilists, somehow suffered for the sake of others—I did not know why or how—but my young heart glowed with admiration of them.

A little later I saw the college brother of my school-chum arrested on the street and spirited away in a droshka. "A politically unreliable," it was whispered about, and the classroom buzzed with the mystic name of Tchaikovsky, and someone asked me whether I would join a literary gathering—a secret TchaĒkovsky circle, he whispered confidentially.

Little by little "Nihilism" became clarified to me. Still were the Bazarovs and Rachmetovs clad in mystery, but Tchernishevsky and Turgenev lit up vague yearnings with a ray of consciousness. It was years later that Socialism and Anarchism crystallized to me as a definite social protest, an inspiring ideal, whose very personification first, appeared to me in the figure of Peter Kropotkin. Again it was Peter Kropotkin who proved my teacher and inspiration all through the years of my later life. It is impossible to estimate the influence of Kropotkin, and of the ideas he has promulgated throughout his whole life, for social ideals flower in manifold paths and carry their seeds into the farthest corners of the world. But this I know, that all through the years of my life as ail Anarchist and all through my prison existence, the personality of Kropotkin—his uncompromising revolution ary spirit and his ideal-kissed vision, have illumined many a day of darkness and warmed despair into cheer and life.

Out of my inmost heart, with love and gratitude I greet you, Peter Kropotkin, my teacher and comrade. As teacher and comrade you are dear, very dear to me; as teacher and comrade you will grow to be appreciated by mankind. And when the soulless scientists of your day have been forgotten and the well-fed philosophers of poverty are lost in tile obscurity of time, the name of Kropotkin, the thinker of revolutionary thought, the scientist of the social regeneration, the true brother of the common man in field, factory and mine, will be the cornerstone of a new humanity and a new civilization.

ALEXANDER BERKMAN.

THE APOSTLE OF ANARCHISM

By J. Morrison Davidson.

A SPECIAL KROPOTKIN number of Mother Earth, apropos of our illustrious comrade's seventieth birthday, is an excellent suggestion, which could not emanate from a more fitting source than Mother Earth Publishing Association, New York, U. S. A. Why, it would be very difficult to sum up the entire Anarchist Gospel according to Prince Kropotkin with more terse exactitude than is done in Mother Earth's standing definition: 'The philosophy of a New Social Order based on Liberty unrestricted by man-made Law; the theory that all forms of Government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.'" Such is the Anarchism of which Kropotkin is the greatest living Apostle, nay, Saint; for some one has, with singular felicity, designated him "the St. Francis d'Assisi of Science." Nor is the element of Martyrdom lacking. It is hardly necessary to recall his shameful incarcerations by Imperial Russia and Republican France, or the heroism with which they were endured. I have never met this blithe-enthused soul—yes, God-inspired, though he believes himself a "Materialist"—but I recall Hamlet's fine, unhackneyable apostrophe to his friend Horatio:—

For thou hast been

As one, in suffering all, that suffers nothing;

A man that fortune's buffets and rewards

Hast ta'en with equal thanks; and blest are those

Whose bloott and judgment are so well commingled

That they are not a pipe for Fortune's finger

To sound what stop she please; give me that man

That is not passion's slave, and I will wear him

In my heart's core, ay, in my heart of hearts,

As I do thee.

But for its Idealists, nay, its Idealist-Materialists, what would this weary, heavy-laden human race come to? A world bereft of Kropotkins, Bakunins and Tolstoys, were indeed a Planet Sorrowful—a realm of unbroken gloom, stagnation, and death. It is their lofty mission to show us how we may confidently

From the future borrow—

Cloathe the waste with dreams of grain,

And on midnight's sky of rain,

Paint the golden morrow.

Personally, like the late Count Tolstoy, I take my Anarchism from the Man of Nazareth; but between the Count's teaching and Kropotkin's I find practically little or no difference. The coin is of pure gold, with reverse as necessary as obverse. The hypostasis of Materialist as of Spiritualist Anarchism is sufficiently familiar: Do you as you would have it done to you in like case. This Golden Rule, once fully realized among men, and the State, Private Property, and Enacted Law must inevitably give place to the Anarchist Commune, already adumbrated in the Russian Mir, of which Madame Kropotkin (may she and gifted Miss Kropotkin be long spared to cheer the sunset glory of our Grand Old Anarchist's days) has written so instructively.

We habitually forget that both the State and Private Property are purely historic formations, "developed parasitically amidst the free institutions of our earliest ancestors"; and unchallenged in their turpitude, except for Kropotkin and a handful of other intrepid thinkers to whom the world owes the deepest debt of gratitude. The Prince's analysis of the "State" is the excalibur of militant Anarchism:

What is this monstrous engine that we call the "State"? It is relatively of modern origin. The State is a historic formation which, in the life of all nations, has, at a certain time, gradually taken the place of free associations. Church, Law, Military Power, Wealth acquired by Plunder, have for centuries made common cause; have, in slow labor, piled stone on stone, encroachment on encroachment; and thus created the monstrous institution which has finally fixed itself in every corner of social life—nay, in the brains and hearts of men—and which we call the State. But rapid decomposition has set in, and, in the next stage of evolution, the Involuntary State will everywhere be replaced by the Voluntary Commune, as if by magic!

Yea, verily the "Conquest of Bread" Commune, when we shall all have to cry out:

Enough! enough coal, enough bread, enough clothes! Let us rest, take recreation; put our strength to better use; spend our time in a better way! From each according to his powers; to each according to his wants!

"And so mote it be!"

Years ago, in dedicating a small historical treatise to our venerable friend, I designated him, natu Princeps Slavonicus, ubique gentium naturaliter Princeps," and, on his seventieth natal day, he is stillFirst—First among Scientists and Humanitarians, the world over.

* * *

HUMANITARIAN AND REVOLUTIONIST

By Max Baginski.

THOSE who believe that a charming personality, a gentle spirit, or a poetic susceptibility are not compatible with aggressive revolutionary activity ought to read Peter Kropotkin's works, especially the "Memoirs of a Revolutionist." There is in his life and work a perfect synthesis of highest devotion to humanity and of revolutionary passion.

Through the realms of nature, the field of science, Kropotkin searches, with the keen and mild eye of the sage, for those facts and experiences which show that mutual aid, comradeship, solidarity are man's finest qualities and at the same time the sources and motives for his material and mental development. He does not discover in this vast realm anything that looks like a supernatural ethic which has the power to command us to do the good, but he finds already in the life of the animals unmistakable traces of sympathetic cooperation pointing toward the cooperative human commonwealth, that leaves the individual free and yet unfolds his social instincts and actions towards a life of equality and justice. Kropotkin's sociology and philosophy make for reconciliation of the individual with society, expleting the icy social abyss which separates man from man like mortal enemies.

This ideal and aim of humanism, Anarchy—nobody has brought its beautiful realization so sympathetically near to the mind and heart as the revolutionist Kropotkin, and nobody has, like him, furnished it with so splendid an intellectual armor.

The Russian government has still every reason to deplore the fact that on June 30, i876, the political prisoner Peter Kropotkin made his miraculous escape from the prison hospital in St. Petersburg. This escape gave to the modern international revolutionary movement its most beloved comrade, its boldest, most inspiring pioneer.

PETER KROPOTKIN

A PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

By Bayard Boyesen.

IN THE college life of the average American youth there is little, if any, intellectual companionship; and the young man whose mind expatiates beyond the spheres of college rules and interests finds himself forced to huddle in a lonely dream. Of course, there are political clubs and literary societies; but the former are not places of thought, and the latter gaze at literature from a viewpoint that denies the "springs of life." Indeed, the students, as well as the authorities, consider it properly "American" to deride all enthusiasms that hitch themselves to anything nobler than a college yell. Once, a Freshman came to me and showed me an essay he had written with a sincerity that was almost terrible in its beauty; and he said to me in a voice that verged on tears: "Look: they told me to write as I felt, and I did so, and this is all the criticism I get: 'Immature.'" I could scarcely believe what he said until I had read the essay again and again, and found nothing for guidance to this youth of sixteen save the professor's illuminating information that the lad was immature!

So the young man of thought and aspiration must find his companionship in books. Lucky he will be if this necessity leads him to a meeting with the works of Kropotkin.

I remember hearing, while I was still an undergraduate, a professor speak blithely about the "margin of labor"; and I remember my astonishment when he said, in the tone of a man making so obvious a remark that it required no substantiation, that it was necessary that there should be, at all times, some men who were unemployed. I, being an impertinent youth —impertinent, because I had a habit of asking pertinent questions—requested to know the reason why; whereupon he, being a learned man, replied: "It is necessary because the conditions of business demand it, because business can't be run without this margin." I then asked him what provision had been made in order to insure to these men "on the margin" and to their families a means of subsistence. But this question he dismissed, since it had, he asserted, nothing to do with economics. I began to think.

Some time afterwards, I was talking with an elderly gentleman, and in the course of a general discussion, I ventured to tell him of the opinions and conclusions I had formed concerning what I still termed economics. To my utter amazement, he said: "So you're an Anarchist." Indignantly I replied that he was simply calling me an odious name, as age is wont to do when it cannot answer the arguments of youth. He smiled benignly. "Read Kropotkin, my boy, and then come and tell me if it is not an honor to be called an Anarchist." He handed me some pamphlets and the "Memoirs of a Revolutionist."

That night I read. I had realized, before, the miseries and perfidies of men; but that night I realized for the first time the hopes and opportunities of Man. The ideal of what I should be—I, too!—spoke to the puny reality of what I was. From the reclusive park of my former imaginings, I looked; looked and saw the rough country around, the unplotted earth, the stubble paths; and I knew that my literary altars must be cast down, and that I, too, must go forth over the unplotted earth, into the stubble paths, and beyond. In my eyes was the vision of an unboundaried nation, unshackled, complete.

But the "Memoirs" were not merely the cause of a temporary exaltation and a vision; they were the basis and beginning of a life-long companionship with the men and women whose thoughts and actions project into previously undiscovered territories, who use the facts and traditions of life not as jackets of restraint, but as springboards into space, who take unabashed, cheerfully, the challenge of existence, and realize that it is only the terrors and perfidies of men that make the opportunity of greatness. Just as my imagination had first seen its possibilities when, as a boy, I came upon the works of Shelley, so here, first, in the work of Kropotkin my heart and mind awoke.

It would not be practical to attempt to set forth in this necessarily short paper even a tithe of what the books of Kropotkin have meant to me and to the young men to whom I have given them. I will, however, present one example of the enduring quality of their influence.

It is difficult for me to speak of Professor Klasovsky without displaying what must seem an exaggerated emotion to those who have never experienced the loneliness of undergraduate aspiration in America; and I cannot, to-day, recall that wonderful little man as he appears in the pages of Kropotkin without a misting of the eyes and something very close to despair of our university education. I wonder whether he did more for Kropotkin than for me. I, of course, never saw him; but often, when I had been listening, perforce, to some professor spreading weak and weary platitudes over the beauties of English poetry, patronizing Shelley as one might patronize a naughty boy, attempting to make the flame-bled slogans of Swinburne seem but a concatenation of gorgeous sounds, or mouthing the steepled prose of Milton without any realization of the fervid spirit behind,—how often then, seeking seclusion, I would run to my imaginary Klasovsky and listen at his feet! What absurdities I must have put into his mouth, what puerile generalizations! Yet what a comfort it was to me to fancy that there was one man of knowledge to whom I could speak out my mind without fear of the worst of rebuffs, the smile of condescending age!

Later, I spent four years in an attempt to teach and educate in the university in which I had been lectured and quizzed. Then, too, I had need of Klasovsky and Kropotkin; for, though I cared not at all for the criticisms my colleagues would bestow upon my unacademic methods, I had need of courage when I saw—how often!—some youth who had entered with enthusiasm and high hopes go down before the drudggeries of the system, flatten out, and disappear.

I might go on to relate a thousand incidents in which the works of Kropotkin have proved of benefit to me and to my fellows; and it would be interesting to me to proceed to an exposition and friendly criticism of his theories. But that was not the purpose of this little essay. I have written it with the intention merely of recording an experience common to many men of my acquaintance and to innumerable others whom neither he nor I can know. If, to-day, it is not given to me to sail so buoyantly upon an optimism so large as his, I still accept his purpose and belief, I still pick up the thumb-worn pages of the "Revolutionist," and there still see the fair crops of the future, though the miseries of the present rot the harvests of to-day. Salve, Kropotkin!

* * *

AN IMMORTAL

THE seventieth anniversary of Peter Kropotkin's birth ought to remind every lover of freedom and beneficiary of science of the debt we owe this courageous and kindly Russian.

There is no reason why those of us who cannot subscribe to his faith in Anarchism should not subscribe to our faith in him. A man who abjures the princely title and who dedicates his life to science, interpreting that in the distinctively twentieth century method of synthesis, although he was the contemporary and colleague of the nineteenth century analytical scientist; a man whose writings are alive with democratic sympathy and who in himself is the incarnation of democracy; a man who has not only repudiated high position, but who has been driven from pillar to post, from country to country, from prison to prison;—such a man commands the respect and homage of every scientific thinker and lover of freedom.

It would be a distinct sacrifice for any humanitarian to deny himself the privilege of paying tribute to this devoted lover of his kind, whose pioneer services and bodily risks have not prevented his attaining his threescore years and ten. Whatever may be the social system of the future, Peter Kropotkin's niche is safe in the universal Hall of Fame.

Charles Zueblin.

A TRIBUTE

IT IS a very happy occasion that has suggested the idea of celebrating the seventieth birthday of our dear Comrade Peter Kropotkin by publishing a special number of Mother Earth. For I am sure there is none who has the slightest regard for the welfare of humanity, who will not rejoice at the thought that he is still alive and well, and still working hard in the great cause, after three-score years and ten of a life that few men could ever hope to have lived.

It would indeed be fairer to call that life a strenuous battle against privilege in all its forms. For it is not only against capitalist exploitation that he has raised his voice, but with equal force and power he has denounced those even more insidious phases of the same evil which authority uses to enslave the mind of man. None wish more than he that all should have well-being; but few unhappily care as he does that the individual should be really free in thought and word and deed.

It may be of interest to your readers to have a few brief details of his work in England so far as it has centered round Freedom, although it must be earnestly hoped that whoso has not yet read his "Memoirs" will take this opportunity of acquainting themselves with the narrative of his life by getting that deeply interesting work.

When in 1886 Kropotkin returned here from France after his imprisonment, there was practically no Anarchist movement in England. The Socialist League, however, had been formed, with William Morris at its head, and had already sounded the note of anti-parliamentarism, clearing the air to some extent for Anarchist ideas. So that when Freedom was started (October, i886) Kropotkin found many interested in the excellent articles he contributed to that paper on the aims and ideals of Anarchist Communism. So much so that a few months later it was found necessary to start a series of meetings at the Socialist League Hall, Farringdon Road, which Morris, with that fairmindedness so characteristic of him, had willingly let to us.

Looking back over a quarter of a century, Kropotkin and those who were with him will recall these meetings, at several of which he explained, in his addresses, Anarchism in its various aspects, necessarily arousing much heated discussion; in which it may be mentioned that amongst others Sidney Webb, Annie Besant, John Burns and Herbert Burrows took part. In spite of developments that have taken place since those early times, there is none of them, I am sure, who will not have good wishes for him on his seventieth birthday.

For those of us who have worked more closely with him, who know how deeply the Anarchist spirit has been manifested by him towards all, irrespective of social or educational disadvantages, looking only for sincerity and conviction—we wish to join with you, comrades of these great United States of America, and add our voice to yours in wishing still for our dear friend Peter Kropotkin years of health, happiness and that activity which is his life. And if there is one hope we hold more fervently than another .it is that he may yet live to see some grand fulfillment of those ideals to which he has devoted the whole of his energies and for which his heart beats as ardently as ever in the seventieth year of his life.

A. Marsh,

Editor of Freedom, London.

* * *

A RARE MAN

WE ARE at a loss to describe or clarify such a character as Kropotkin; accepted standards are usually false, and the terminology at our disposal lacks comprehensiveness. When the orator or eulogist fails, in his opinion, to adequately characterize his subject, he usually falls back on some such phrase as "we like him best of all because he is human." This is considered the greatest of compliments, and oftimes kings are exalted by their subjects and flatterers because they are "human." Certain it is, Kropotkin is human in the sense that he has a commonality of interest with his fellow-men and is not without human weaknesses, but the phrase is faulty, incomplete, as it fails to imply that we love him because he is a rare human being. Bernard Shaw makes Blanco Posnet say, "there is no good and no bad, but there's a great game and a rotten game." Good and bad are relative terms, but we love those who play the great game and despise those who play the rotten one.

Happy indeed is the man who has found his work, and thrice happy should he be if the work has a social value. To live is ordinary, to live well and with a purpose, extraordinary—it makes for that immortality all should strive for, to be a force and live in the hearts of our fellow-men after we have crossed the Styx. With a combination of gifts rare in man, Kropotkin has lived to a purpose, and his work will live after him. Scientist, explorer, man of letters and social revolutionist, this remarkable man has combined these and ma,ny other qualities with a humanity as deep as the springs of life, and. as broad as the vision of our greatest age. Humanity, with its endless roll of great thinkers, poets and humanitarians, has produced many men and women as great in one or more particulars; it is the combination of great talents, the harmony of scientist, social prophet, man of action and great humanitarian that makes him rare among the rarest of mortals.

His "Mutual Aid" humanized and put the sweetness of life into the Darwinian theory and bids humanity have hope for better days. "Fields, Factories and Workshops" attacks the God of Efficiency that would degrade and destroy the soul of man for a greater productivity of things, and points out the necessity for well-rounded and fully developed men if we are to have a free society. His "Conquest of Bread" and "Memoirs," analytic and constructive, show the seer and prophet as well as the worker and man of action. What niche in the pantheon of fame future historians will assign him we know not; that it will be a high one we can not doubt. An inspiration and guiding star for men and women of all lands, his influence will grow and expand. To those of us who have known him personally our lives have been better and our wisdom larger for having met, known and learned to love this wonderful personality, a personality symbolized by a name—Peter Kropotkin.

Harry Kelly.

KROPOTKIN AS A SCIENTIST

BY WHATEVER path the social revolution comes, all of us who have our faces towards that supreme event, do gladly join in our tribute to the worth and work of Peter Kropotkin. The Socialist tendency of to-day is to generously recognize all persons and forces that are making for the great change. It is as a revolutionary Socialist that I hail Peter Kropotkin, on his celebration of his seventieth birthday, and wish that he yet may have many years wherein to continue his devoted and heroic labors. It was as a Socialist, and with the approval of my comrades in New York City, that I presided over the great mass meeting that welcomed him to New York City eleven years ago. I shall always gratefully remember—though probably he has forgotten—the afternoon conversations I had with him when I was attending lectures at the London School of Economics, fifteen years ago. He did not at all approve of my way of looking at things at that time, either sociologically or religiously; but he was always so kindly and so reasonable in his admonitions and arguments, that I found him a vastly better teacher than the Fabian professors of political economy who constituted the faculty of the School of Economics. And though I still look for the great change to come by a very different highway from that by which he thinks it will come, I yet wish to say that no man since Marx or Darwin has made a more ultimate or permanent a contribution to the social future than Kropotkin has made. I also wish to join my word to the words of those who will speak of Kropotkin's sterling personal worth, as well as of his career as a Russian revolutionist, as one of the greatest men of science, and as a great man of letters.

There is one special phase of Kropotkin's work that I do not think is yet sufficiently valued or understood. I refer to his emphasis on the cooperative tendency in nature, as against the competitive tendency so insistently emphasized by the older evolutionists. The Darwinians have outdone their master in calling attention to the struggle for existence—in sharpening the tooth and claw. It is only Kropotkin, so far as I know, who has, as a scientist, called attention to the struggle for fellowship that is as truly manifest in nature as the competitive struggle. He alone among scientists has called attention to the fact that the strongest in the competitive struggle do no survive; they extinguish one another. A merely competitive nature would be nature's self-destruction. Ultimate survival has been concurrent with cooperation. The types that really survive, in- the long course of things, are the types that cooperate, the types that attain to fellowship. Biologically, or physiologically, these types are often, if not generally, the weakest. If we were to change this from scientific into more familiar phraseology, we would say that it seems to be a law of nature that the meek inherit the earth, in the end; that it is not the fighter, but the lover who will ultimately prevail. Even to the materialist, there seems to be some reason in or behind nature that lends the last results of power to love, and snatches them from hate. It is war, it is the struggle for existence, it is the competition between man and man or tribe and tribe or nation and nation, that has wrought the waste places of the earth. Even the jungles of Africa are now found to have been the seats of mighty civilizations, of immense and splendid cities and temples, destroyed by the competitions of races. It is possible that the great deserts of the world are the result of man's destruction of man. The scientists tell us that the Black Plague originated upon a battlefield where a hundred thousand dead were left unburied. Forests are denuded, great rivers are dried up, rain-falls are ended, through the fierce competition of industrial man, while cooperation and social control are able to restore the forests, the rain-falls and the rivers. It is literally true that nature so favors cooperation that the cooperative man could make the solitary places of the earth glad, and the wilderness blossom as a rose, and the world like unto a kingdom of heaven.

I have called attention to this special emphasis which runs through Kropotkin's writing, and which makes his "Mutual Aid Among Animals" one of the greatest and most instructive books ever written. There is no book more useful to the Socialist, the Single-taxer, or the Philosophical Anarchist. Peter Kropotkin has made an immense and yet unappropriated contribution both to the knowledge of nature and to sociology. I am sure that the greatest honor we could pay him in his seventieth birthday, and the one that would give him the greatest gratitude, would be to appropriate his immeasurable contribution.

George D. Herron.

Florence, Italy, Oct. 8, 1912.

* * *

A GREETING

Dear Comrade:

You ask me to tell you what I think of Kropotkin for the number which you intend to publish on the occasion of his seventieth birthday.

What can I say except what everyone says who is acquainted with him?

I know of no man more loyal than he, more enthusiastic, more youthful in spite of his seventy years, and at the same time there is no one so simple, so modest.

To appreciate his disinterestedness, it is only necessary to be aware of his origin, and his sacrifice of wealth and honors to consecrate himself to the propagation of ideas which could bring him nothing but imprisonment and persecutions on all sides, even to the extent of a death sentence in his native land.

Everybody knows the position which he has won for himself in the scientific world.

Therefore the example of his life seems to me to refute perfectly the imbecilities of those "worshippers of the horny hand"—ex-workingmen—who hold that the "intellectuals" never come to the working class for any purpose except to dominate it.

Without taking into account that the term "intellectual" has absolutely no significance and means simply a man who has not sprung from the working class; for where is the manual labor which does not require brain work, and how many so-called "intellectuals" are less intellectual than those whom some people call "common workingmen"? Now then? . . .

Cordial greetings,

Jean Grave.

* * *

A KROPOTKIN INTRODUCTION

THE non-Anarchist stranger walked in shyly behind the old-friend-of-prison-days. A great event was to take place in her life. She was to see Kropotkin—to meet him—to speak to him! The old-friendof-prison-days had said to her simply just like this: "I am going to Kropotkin's. If you want, you can come along."

She looked at him strangely. If she wanted! Is it possible that in his close intimacy with the man, he had forgotten what that name meant to the youth? It had been part of her being. She had grown up conscious of its meaning, not remembering when or how it first came to her. It belonged to the breath she drew, to the glowing life within her. Once she had heard the "Appeal to the Youth" read at a Socialist meeting. Somehow she knew beforehand those inspired words. His name alone had made the appeal to humanism and solidarity even before she read him. It was by his life that he taught. And the youth—it held communion with him through his living personality, through his memoirs, through those little black covered volumes with the large white letters, the books of Kropotkin and Anarchism, which the ardent souls in Russia carry along with them in their hazardous work of propaganda and agitation.

And now she was to see him—to slip in quietly behind the old-friend-of-prison-days and meet him.

They sat on the top of a 'bus and talked Kropotkin, he telling her how they met for the first time in the warden's office of a prison in St. Petersburg. It had a splendid name—that prison. The House of Detention Before Trial. She, too, knew those crumbling walls with the splendid name. She had been whisked through it for a day. Only a day? Never mind. It gave her the chance to sit with the old-friend on this 'bus to go to Kropotkin's.

"That was about forty years ago when we two met," he said. "How old we are getting. No, not Kropotkin. You will see, he has green youth."

Yes. So young he was! He walked briskly across the room, and so straight—almost like an official at the court. But his greeting was hearty and his face warm with love, and just like his portraits seen everywhere. There lay his big beard spread out upon his chest, and his head thrown back military fashion, looking quite hairless in contrast with his beard. There he was, his portrait came down from the wall. It was as he should look, and she felt she had always known him in person.

He had not been feeling well, he said. The old-friendof-prison-days whose hearing had been almost ruined and whose whole constitution undermined in Siberia, looked solicitous. "You, too, my dear?" he said.

Kropotkin smiled. It will soon pass away, he answered. "And you," he said, turning to the newcomer, "tell me what are they going to do in America."

She did not know. She had left America as a student and had been away many years, but she had just read. It was not as blatant a country as when she left. There was the Moyer, Pettibone and Haywood trial just finished, and besides this awakening of the workers, there seems to be a breaking up of the old bourgeois traditions. She reads on all sides a concerted attack on the constitution.

Why did she say that! It was shyness that made her talk so stupidly. "Constitution"! As if she, too, believed in its potency. Could she not have told him of something more fundamental, something which pertains really to the life of the people! But it was too late. Already Kropotkin was striding up and down the room, blazing forth in wrath. What hope was there of a new social era, if the youth still tinkered with the enemy's tools! One must find new forms entirely, create one's vision anew and hold it ever before one clear and distinct that even its edge might be reached. We cannot go forward dragging the old with us, and we must speak of words written in blood, not paper!

True—but if he were not so angry she would explain, she would acknowledge herself wrong; but how angry he was and how quickly he became angry! Besides, it was a sign of the times. She said so.

Again great wrath. It was no sign at all—it meant nothing, it was no matter for the youth to soil their hands with. She seemed to have pricked a whole hornet's nest of wrath.

Did he really think she was not one of his? How sad that was.

Suddenly she felt a hand laid tenderly on her head. "How are your dear people?" he asked. She smiled up into his face, which now looked down kindly at her. "And tell me what you did in Russia?" He never for a moment mistook her, but such a careless talker, and a careless thinker, too—almost.

There was a frown and a swift shrug of the shoulders. Would it break out again? No—there was laughter. The erstwhile stranger was to have dinner and then spend the rest of the day. There was talk of parties in Russia, of the growing consciousness of the people and of mutual friends.

It had all become so simple again, just as when the old-friend had said, "If you want, you can come along with me to Kropotkin's." There they sat and talked, familiarly, not as old friends, but as if one who had been gone many years had just returned and there was talk of new things concerning old friends.

The friend-of-prison-days and the non-Anarchist stranger sat again on the top of a bus.

"He frightened you?" the old-friend asked, laughing. "But he always does it."

"Why?" she asked.

"To test his love perhaps. He knows he can love. I fancy he wonders if he still has the iron in it."

ROSE STRUNSKY.

KROPOTKIN AS PHILOSOPHER AND WRITER

WHAT is especially characteristic of the works of Peter Kropotkin, what appeals to us most is his high idealism, his wide outlook over the whole field of sociologic thought, an outlook that constantly opens up to us new vistas of man's possibilities.

His work, "Conquest of Bread," is a revolutionary idyl, a beautiful Kulturbild, that sketches in broad outline future society as it may be formed, after the storm period of the Social Revolution, by the spontaneous efforts of the working masses.

Indeed, we do not blind ourselves to tile difficulties of the great struggle, nor that these, in their practical realization, may even prove greater than indicated by the author. But what appeals to us most forcibly is the grand conception of the problems to be solved and the wealth of new ideas suggested by the author along various lines of thought. The manner in which Kropotkin presents in this book, as well as in all of his scientific works, the broad lines followed by the progress of human civilization, carries us along with almost irresistible force and inspires us to greater effort and struggle, without our closer examining whether the milestones, marked out by the author, are to be reached so soon—indeed, whether they may ever be reached at all.

In this regard the philosophic and scientific works of Kropotkin exert upon the revolutionary reader an effect similar to the preachments and revelations of the gospel upon the early Christian societies.

On the other hand, Kropotkin's ideas concerning the cooperation of industry and agriculture, of the combination of intellectual work with manual labor, of mutual aid in the animal and human world, have exerted an influence that is reaching far beyond the revolutionary labor movement.

The same broad conception that characterizes the scientific labors of Kropotkin permeates also his autobiography. Generally speaking, autobiographies are thankless tasks, because personal life stories are of but little value as reliable historic sources. Most autobiographies are nothing more than advertisements of the author, who usually incorporates in his book letters and documents favorable to himself, while suppressing everything that might have an opposite effect.

How different in this regard' is the autobiography of Peter Kropotkin! How little space he devotes to speaking of himself and how thoroughly he deals with the conditions and environment of his time, how objective his descriptions of the persons he came in contact with.

Perhaps the readers of his "Memoirs" could have formed their estimate of Kropotkin if he had limited himself only to facts and data. But how we should have missed his objective characterization of persons, environment, and events! The very brevity with which Kropotkin speaks of himself, the warmth and deep understanding with which he treats everything outside his personal "I," are the features which in his "Memoirs" produce the same charm upon his readers as the most beautiful passages of his scientific works. The theoretical exposition of his views on economic and social questions and his personal reminiscenses complement each other in the happiest manner.

Paris. CHRISTIAN CORNELISSEN.

* * *

KROPOTKIN makes us ready to compare our time with any period of history. We must go back generations, if not centuries indeed, before we can find anyone of his ability equally at home in science, literature, history and social philosophy. The quality of Kropotkin's revolutionism can only be gauged by his quality as a thinker and a man; no aspect of life and no aspect of the movement towards a new society has failed to interest him. But we cannot measure Kropotkin's value either by the breadth of his revolutionism or by his contributions to the life and thought of the time. He is great because his revolutionism inspires every word he writes and because at the same time his universal culture is the basis of all his revolutionism. This is why we have in Kropotkin beyond question the greatest living fore— runner of the civilization of the future.

WM. ENGLISH WALLING.

THE STERILIZATION OF THE UNFIT