Emma Goldman's Tribute to Voltarine de Clyre

<--Previous Up Next-->

High Resolution Image

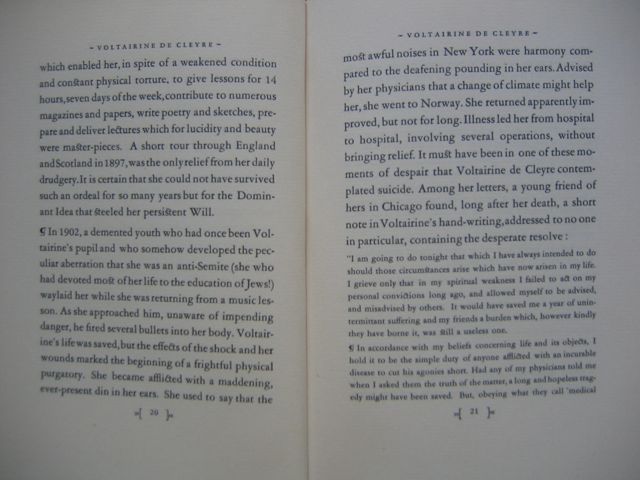

which enabled her, in spite of a weakened condition and constant physical torture, to give lessons for 14 hours, seven days of the week, contribute to numerous magazines and papers, write poetry and sketches, prepare and deliver lectures which for lucidity and beauty were master-pieces. A short tour through England and Scotland in 1897, was the only relief from her daily drudgery. It is certain that she could not have survived such an ordeal for so many years but for the Dominant idea that steeled her persistent Will.

In 1902, a demented youth who had once been Voltairine’s pupil and who somehow developed the peculiar abberration that she was an anti-Semite (she who had devoted most of her life to the education of Jews!) waylaid her while she was returning from a music lesson. As she approached him, unaware of impending danger, he fired several bullets in her body. Voltairine’s life was saved, but the effects of the shock and her wounds marked the beginning of a frightful physical purgatory. She became afflicted with a meddening, ever-present din in her ears. She used to say that the most awful noises in New York were harmony compared to the deafening pounding in her ears. Advised by her physicians that a change of climate might help her, she went to Norway. She returned apparently improved, but not for long. Illness led her from hospital to hospital, involving several opperations, without bringing relief. It must have been in one of these moments of despair that Voltairine de Cleyre contemplated suicide. Among her letters, a young friend of hers in Chicago found, long after her death, a short note in Voltairine’s hand-writing, addressed to no one in particular, containing the desperate resolve:

“I am going to do tonight that which I have always intended to do should those circumstances arise which have now arisen in my life. I grieve only that in my spiritual weakness I failed to act on my personal convictions long ago, and allowed myself to be advised,and misadvised by others. It would have saved me a year of unintermittant suffering and my friends burden which, however kindly they have borne it, was still a useless one.

In accordance with my beliefs concerning life and its objects, I hold it to be the simple duty of anyone afflicted with an incurable disease to cut his agonies short. Had any of my physicians told me when I asked them the truth of the matter, a long and hopeless tragedy might have been saved. But, obeying what they call ‘medical

|