Living My Life

by Emma Goldman

Volume Two

New York: Alfred A Knopf Inc., 1931.

Chapter 48

THE ESPIONAGE ACT RESULTED IN FILLING THE CIVIL AND MILITARY prisons of the country with men sentenced to incredibly long terms; Bill Haywood received twenty years, his hundred and ten I.W.W. co-defendants from one to ten years, Eugene V. Debs ten years, Kate Richards O'Hare five. These were but a few among the hundreds railroaded to living deaths.

Then came the arrest of a group of our young comrades in New York, comprising Mollie Steimer, Jacob Abrams, Samuel Lipman, Hyman Lachowsky, and Jacob Schwartz. Their offence consisted in circulating a printed protest against American intervention in Russia. Every one of those youths was subjected to the severest third degree, and Schwartz fell dangerously ill as a result of savage beating. They were kept in the Tombs, where large numbers of other radicals were also awaiting trial or deportation, among them our faithful "Swede." Their brave, determined stand for an ideal's sake glaringly contrasted with Ben's inconsistency. His attempt to offer his medical services to the army had capped the climax. If his prison term were at last served, I felt, it would give me the strength to emancipate myself from him, to become free from my emotional bondage. In this hope I had pestered Stella and Fitzi to raise his fine, so that he should not have to serve more time in payment. But my fear had been groundless; the fine was remitted before his release. Ben did not even have the grace to inform me or the girls in New York about it. I received the news from Agnes Inglis, one of my dearest and most considerate friends, who came to visit me in prison. Later Ben wrote me; he told all about his son, his mother, his wife, and his plans and urged me to see him. I did not consider that his letter required a reply.

Agnes Inglis was the type to whom friendship was a sacrament. Never once did she fail me after we first came in close contact in 1914. She had been attracted to my work, she once told me, by my pamphlet What I Believe. She belonged to a wealthy family of orthodox Presbyterians, and it involved a great inner conflict to free herself from the middle-class morality and traditions of her environment, but with rare spiritual courage she overcame her heritage and gradually developed into a woman of independent and original attitude. She gave most generously of her time, energy, and means to every progressive cause and always participated in our campaigns for free speech. Agnes combined her active interest in the social struggle with a broad humanity in personal relations. I had come to appreciate her qualities as comrade and friend, and it was a great treat to have her visit me for two days.

Before she left the city, she called once more at the penitentiary, and the head matron brought her to the shop. I had not expected her and was startled when I saw Agnes standing in the door of our treadmill. Her affrighted eyes roved all over the place, finally settling on me. She started to walk towards my machine, but I stopped her with a gesture and then waved her my good-bye. I could not endure a demonstration of our affection in the presence of my shop-mates, who had so little of it in their own lives.

The war for democracy was celebrating its triumphs at home as abroad. One of its characteristic features was the dooming of Mollie Steimer's group to long prison terms. They were all mere youths. Yet United States District Judge Henry D. Clayton, a veritable Jeffreys, sentenced the boys to twenty years' imprisonment and Mollie to fifteen, with deportation at the expiration of their terms. Jacob Schwartz had been saved His Honour's mercy; he had died on the day of the opening of the trial, from injuries inflicted upon him by police blackjacks. In his Tombs cell was found an unfinished note in Yiddish, written in his dying hour. It read:

- Farewell, comrades. When you appear before the Court I will be with you no longer. Struggle without fear, fight bravely. I am sorry to have to leave you. But this is life itself. After your long martyr--

"The intelligence, courage, and fortitude shown by our comrades at their trial, particularly by Mollie Steimer," a friend wrote to me, "was profoundly impressive." Even the newspaper men could not help referring to the dignity and strength of the girl and her co-defendants. These comrades had come from the working masses and were hardly known even to us. By their simple act and magnificent bearing they had added their names to the galaxy of heroic figures in the struggle for humanity.

The torrent of war news would have submerged the important case on trial before Judge Clayton but for the acumen of counsel for the defence. Harry Weinberger realized the significance of the underlying issues and he called on the witness-stand men of national reputation, thereby compelling the press to take notice. He subpoenaed Raymond Robins, one of the heads of the American Red Cross in Russia, and Mr. George Creel, of the Federal Information Bureau, who had been responsible for the so-called "Sisson documents." Thus the truth was exposed about the deliberate attempt to prejudice the world against Russia by forgeries which were to serve as ground for military intervention against the Revolution. Weinberger showed that President Woodrow Wilson had, without the knowledge of the people of the United States and without the consent of Congress, illegally sent American troops to Vladivostok and Archangel. Under those circumstances, he declared, the defendants had done a just and laudable act in calling public attention by their protest against waging war with Russia, with which America was officially at peace.

The influenza epidemic raging through the country had reached our prison, and thirty-five inmates were stricken down. In the absence of any hospital facilities, the patients were kept in their cells, exposing the other inmates to infection. At the first sign of the disease I had offered my services to the physician. He knew I was a trained nurse and he welcomed my aid. He promised to see Miss Smith about letting me take care of the sick, but days passed without bringing results. Later I learned that the head matron had refused to take me out of the shop. I was already enjoying too many privileges, she had said, and she would not stand for more.

Not being officially permitted to nurse, I sought means to aid the sick unofficially. Since the influenza invasion our cells were being left unlocked at night. The two girls assigned to nursing were so hard-worked that they would sleep all through the night, and the orderlies were my friends. That offered me a chance to make hurried calls from cell to cell and do what little was possible to make the patients more comfortable.

On November 11, at ten in the morning, the electric power in our shop was switched off, the machines stopped, and we were informed that there would be no further work that day. We were sent to our cells, and after lunch we were marched to the yard for recreation. It was an unheard-of event in the prison and everyone wondered what it could mean. My thoughts dwelt in the days of 1887. I had intended to strike against work on the anniversary that marked the birth of my social consciousness. But there were so few women able to go to the shop that I did not want to add to the number of absentees. The unexpected holiday gave me the opportunity to be alone for spiritual communion with my martyred Chicago comrades.

During recreation in the yard I missed Minnie Eddy, one of the inmates. She was the most unfortunate creature in the prison, constantly in trouble about her work. Though she tried very hard to complete the allotted task, she seldom succeeded. If she rushed, her work was bad; if she slowed down, she failed to finish the day's work. She was bullied by the foreman, reprimanded by the head matron, and often punished. In her desperation Minnie spent the few cents she received from her sister to pay for help. She was very appreciative of the least kindness and she became inseparable from me. Of late she had been complaining of dizziness and severe pain in the head. One day she had fainted away at her machine. It was apparent that Minnie was seriously ill. Yet Miss Smith refused to exempt her from work. The woman was shamming, the matron claimed, though we knew better. The doctor, by no means a brave or aggressive man, would not dispute Lilah.

Failing to see Minnie in the yard, I assumed that she had probably received permission to remain in the cell. But when we returned from recreation, I discovered that she was in punishment, locked up on bread and water. We expected her to be released the next day.

Late in the evening the prison silence was torn by deafening noises coming from the male wing. The men were banging on bars, whistling, and shouting. The women grew nervous, and the block matron hastened over to reassure them. The declaration of armistice was being celebrated she said. "What armistice?" I asked. "It's Armistice Day," she replied; "that's why you have been given a holiday." At first I hardly grasped the full significance of the information, and then I, too, became possessed of a desire to scream and shout, to do something to give vent to my agitation. "Miss Anna, Miss Anna!" I called the matron back. "Come here, please, come here!" She approached again. "You mean that hostilities have been stopped, that the war has come to an end and the prisons will be opened for those who refused to take part in the slaughter? Tell me, tell me!" She put her hand soothingly on mine. "I have never seen you so excited before," she said; "a woman of your age, working yourself up to such a pitch over such a thing!" She was a kindly soul, but she knew nothing outside her prison duties.

Minnie Eddy was not released the next day, as I had hoped she would be. On the contrary, suspecting that someone was secretly feeding her, the head matron ordered her transferred to the blind cell. I pleaded with Miss Smith that Minnie might die if she continued on bread and water and was forced to sleep on the damp floor. Lilah told me gruffly to mind my own business. I waited another few days and then I notified the Warden that I had something urgent to see him about. Miss Smith no doubt suspected the contents of my sealed envelope, but she did not dare hold back letters addressed to Mr. Painter. He came, and I reported Minnie's case to him. The same evening Minnie was sent back to her cell.

On Thanksgiving, she was allowed to come to the dining-room for the special dinner, which consisted of pork of questionable quality. Starved for days, she ate ravenously. A week before, her sister had sent her a basket of fruit, and as a privilege Minnie was permitted to receive it. Most of it had meanwhile become decayed, and I warned her not to touch it, promising to send her eggs and other things from my supply. At midnight the coloured orderly woke me to say that she had heard Minnie cry in pain, and when she had reached her cell, she had found the woman in a faint on the floor. Her door was locked and she did not dare call Miss Smith. I insisted that she must be summoned. After a while we heard groaning in Minnie's cell, followed by sobbing, and then the matron's receding steps. The orderly reported that Miss Smith had poured cold water over Minnie, struck her several times, and ordered her to get up from the floor.

The following day Minnie was placed in an isolated rear cell, with only a mattress on the floor. She became delirious, her cries resounding through the corridor. We learned that she had refused nourishment and that an attempt at forcible feeding had been made. But it was too late. She died on the twenty-second day of her punishment.

The misery and tragedies of prison life were aggravated by sad news from the outside. My brother Herman's wife, our beautiful Ray, had died from heart-trouble. Helena also was in a terrible state of mind. No word from David had reached her for weeks, and she was beside herself with dread that something might have happened to him.

A ray of light came with the commutation of Tom Mooney's death-sentence to life imprisonment. It was a travesty on justice to immure a man for life who had been proved innocent by the State's own witnesses. Nevertheless, the commutation was an achievement, due mostly, I felt, to the effective work our people had done. Without the campaign Sasha, Fitzi, and Bob Minor had inaugurated in San Francisco and New York, there would have been no demonstrations in Russia and other European countries. It was the international scope of the Mooney-Billings case that had impressed President Wilson to the extent of inducing him to cause a Federal investigation. The same moral force had prompted him to intercede with the Governor of California for Mooney's life. The agitation organized by Sasha and his associates had at last snatched Tom Mooney from death. Time was thereby gained for further work to give Mooney and Billings liberty. I was happy at these developments and proud of Sasha and the success of his strenuous efforts. I fervently wished that he might be free to bring to completion the victory which had come near costing his own life.

The prison had been quarantined and all visits stopped, excepting of course the incoming and released prisoners. Several new ones arrived, among them Ella. She was sent up on a Federal charge and she brought to me what I had been missing so much --- intellectual companionship with a kindred spirit. My fellow inmates had been kind to me and I had not lacked affection, but we belonged to different worlds. It would have only made them self-conscious of their lack of development had I broached my ideas to them or discussed the books I read. But Ella, though still in her teens, shared my conception of life and values.

She was a proletarian child, familiar with poverty and hardship, strong, and socially conscious. Gentle and sympathetic, she was like a beam of sunshine, bringing cheer to her fellow prisoners and great joy to me. The women reached out for her hungrily, though she was an enigma to them. "What are you here for," one inmate asked Ella--"picking pockets?" "No." "Soliciting men?" "No." "Selling Dope?" "No," laughed Ella, "for none of these things." "Well, what else could you have done to have got eighteen months?" "I am an anarchist," Ella replied. The girls thought it funny to go to prison for "just being something."

Christmas was approaching and my companions were in nervous wonderment as to what the day of days would bring them. Nowhere is Christianity so utterly devoid of meaning as in prison, nowhere its precepts so systematically defied, but myths are more potent than facts. Fearfully strong is their hold on the suffering and despairing. Few of the women could expect anything from the outside; some had not even a single human being to give them a thought. Yet they clung to the hope that the day of their Saviour's birth would bring them some kindness. The majority of the convicts, of infantile mentality, talked of Santa Claus and the stocking with naïve faith. It served to help them over their degradation and misery. Forsaken by God, by man forgot, it was their only refuge.

Long before Christmas, gifts began to arrive for me. Members of my family, comrades, and friends fairly deluged me with presents. Soon my cell began to look like a department store, and every day brought additional packages. As usual, our dear Benny Capes, in response to my request for trinkets for the inmates, sent a huge consignment. Bracelets, ear-rings, necklaces, rings, and brooches, enough to make the Woolworth stock feel ashamed, and lace collars, handkerchiefs, stockings, and other things sufficient to compete with any store on Fourteenth Street. Others were equally generous. My old friends Michael and Annie Cohn were particularly lavish. An invalid for years and in constant torment, Annie was yet most thoughtful of others. She was indeed a rare spirit of brave patience and selfless kindness. Our staunch friends for a quarter of a century, Annie and Michael had always been among the first to come to our assistance whenever aid was needed, co-operating in our efforts in the movement, sharing our burdens, helping and giving without stint. Hardly a week had passed since my imprisonment without a cheering letter and gifts from them. For Christmas Annie sent me a special parcel --- everything prepared with her own hands, as Michael affectionately wrote. Wonderful Annie, a martyr to physical ailments, steadily growing worse, her suffering increasing, living only in her devotion to others!

It was a problem to divide the gifts so as to give each what she might like best, without arousing envy or suspicion of preference and favouritism. I called to my aid three of my neighbours, and with their expert advice and help I played Santa Claus. On Christmas Eve, while our fellow-prisoners were attending the movies, a matron accompanied us to unlock the doors, our aprons piled high with gifts. With gleeful secrecy we flitted along the tiers, visiting each cell in turn. When the women returned from the cinema, the cell-block resounded with exclamations of happy astonishment. "Santa Claus's been here! He's brung me something grand!" "Me, too! Me, too!" re-echoed from cell to cell. My Christmas in the Missouri penitentiary brought me greater joy than many previous ones outside. I was thankful to the friends who had enabled me to bring a gleam of sunshine into the dark lives of my fellow-sufferers.

On New Year's again the prison was filled with noisy hilarity. Fortunate indeed are they whom each year brings nearer to the passionately longed-for hour of release. Not so the poor creatures sent up for life. No hope or cheer for them in the new day or new year. Little Aggie kept to her cell, wailing over her fate. A piteous sight the poor woman was, withered at thirty-three, her years spent in the penitentiary since she was eighteen. She had been condemned to death for killing her husband. The murder was the result of a drunken card-row between Aggie's husband and the boarder. It probably was not the young bride who had wielded the fatal poker, but her "own man" had managed to wriggle out of responsibility. He had turned State's evidence and had helped to send the child to her doom. Her extreme youth had saved her from the noose; her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. I found Aggie one of the sweetest and kindest of beings, capable of strong attachments. After she had been in prison ten years, she was permitted to keep a dog some visitor had given her. His name was Riggles, and an ugly beast he was. But to Aggie he was beauty personified, the most precious thing she possessed and her only tie in life. No mother could have given greater love and attention to her child than Aggie gave her pet. She would never ask anything for herself, but for Riggles she would beg. The brightening of her otherwise dead eyes when she would take Riggles into her arms was a key to the heart-hunger of the unfortunate the law's stupidity had stamped a hardened criminal.

And there was my other neighbour Mrs. Schweiger, a "bad woman," as the head matron called her. A devout Catholic, tragically mismated, she could find no escape in divorce. III health, which unfitted her for child-bearing, added to the misery and loneliness of her life. Her husband sought distraction with other women, and she was left to brood and weep, a prisoner in her own home. In a fit of homicidal melancholia she had emptied a pistol into him. She was of German parentage, which did not add to Lilah Smith's liking for her.

With the New Year came the shock of David's death. For months rumours of the boy's end had hung like a pall over his family. Helena's appeals to Washington for news of her son had brought no results. The United States Government had done its duty; it had shipped David with thousands of others to the fields of France. It could not be bothered by the anguish of those left behind. It was from an officer returned from France that Stella had learned of Dave's tragic fate.

The boy had preferred a responsible position, though dangerous, to the safety of the military orchestra to which he had been assigned, his comrade reported to Stella. He lost his life on October 15, 1918, in the Bois de Rappe, in the Argonne forest, killed one month before Armistice Day, in the prime and glory of his youth. My poor sister was still ignorant of the blow awaiting her. She would be informed as soon as official confirmation was received, Stella's letter said. I foresaw the effect of the terrible news on Helena and I felt sickening apprehension for her sake.

For the first time in months I had a caller again, our dear friend and co-worker M. Eleanor Fitzgerald --- "Fitzi." Following our imprisonment she had accepted a position with the Provincetown Players, where she worked as arduously as she had with us. At the same time she continued her activities in the Mooney-Billings campaign, the Political Prisoners' Amnesty League, and as well took care of our boys in prison. I realized only when I saw her again how hard she must have been working. She looked worn and fatigued, and I regretted having scolded her in a letter because she had not written me in a long time.

She came to Jefferson on her way back home from the Mooney Conference in Chicago. She had also gone to see Sasha in Atlanta. Her visit with him, she told me, had proved most unsatisfactory, because it had been very brief and under a rigid watch. But she had managed to smuggle out a note from him to me. I had had no direct word from Sasha since the last day of our trial, a year before, and the familiar handwriting brought a lump to my throat. Fitzi's replies to my questions were evasive, and I suspected that all was not well with Sasha. He was having a frightful time of it, she reluctantly admitted. He had been put in the dungeon for circulating a protest to the Warden against the brutal clubbing of defenceless prisoners. He had earned the bitter enmity of the officers by denouncing the unprovoked murder of a young Negro inmate who was shot in the back for "impudence." All his Christmas parcels, except one, had been denied him. The other gifts sent to him had graced the dinner- table of the officials. He looked haggard and sick, Fitzi said. "But you know Sasha," she hastened to add; "nothing can break his spirit or dampen his sense of humour. He joked and laughed while I was with him and I joined in, choking back my tears." Yes, I knew Sasha, and I was certain he would survive. Only eight months more --- had he not shown his powers of endurance during his fourteen years in Pennsylvania?

Fitzi could tell me little that was encouraging about the Mooney Conference in Chicago, which she had helped to organize. Most of the labour politicians were busy side-tracking the Mooney activities, she informed me. There was a disheartening lack of unanimity in favour of a general strike in behalf of Mooney and Billings. Moreover, there was evidently a deliberate attempt to hush up publicity. More "diplomatic" methods were to be used to liberate the men. The participation of anarchists was to be discouraged. They had been the first to sound the alarm in the San Francisco cases, and Sasha had consecrated himself to the work, even at the jeopardy of his own life. Now the anarchists and their efforts were to be eliminated from the fight. It was not the first time, nor would it be the last, that anarchists burned their fingers in pulling the chestnuts out of the fire for others, but if Billings and Mooney should regain their freedom, we should feel our work amply repaid. Fitzi, of course, had no intention of relaxing her efforts to bring about a general strike, and I knew that the brave girl would do her best.

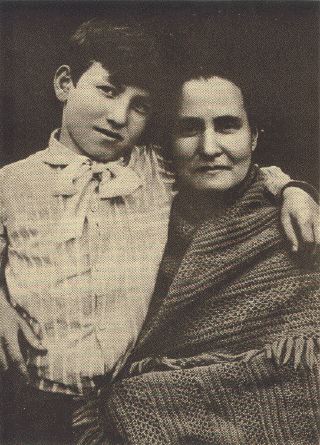

The hardest thing to bear in prison is one's utter powerlessness to do aught for one's loved ones in distress. My sister Helena had given me more affection and care than my parents. Without her my childhood would have been even more barren. She had saved me many blows and had soothed my youth's sorrows and pains. Yet in her own greatest need I could do nothing to help her.

If only I could believe that my sister was still able, as in the past, to feel the suffering of humanity at large, then I would point out to her that there were other stricken mothers, their loss no less poignant than hers, and other tragedies more appalling even than David's untimely death. In former days Helena would have understood, and her own grief might have been mellowed by universal suffering. Would she now? From the letters of my sister Lena and of Stella I could see that Helena's springs of social sympathy had dried up with the tears she had shed for her son.

Time is the greatest healer, and it might also heal my sister's wounds, I thought. I held to that ray of hope and I looked forward to my approaching release, when I might take my darling away somewhere and perhaps bring her a little peace by loving communion.

My sorrow was augmented by still another loss, that of my friend Jessie Ashley, valiant rebel. No other American woman of her position had allied herself so completely with the revolutionary movement as Jessie. She had taken a vital part in the I.W.W. activities, the free-speech and birth-control campaigns, giving personal service and much of her means. She had been with us in the No-Conscription League and in every move we had made against the draft and the war. When Sasha and I were held under fifty-thousand-dollar bail, Jessie Ashley was the first to contribute ten thousand dollars in cash towards our bond. The news of her death after a short illness had come unexpectedly. David and Jessie --- one of my own blood, the other much closer in spirit --- their passing affected me deeply. Yet it was the horrible fate of two other persons, known to me by name only, that proved even a greater blow --- that of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

Social democracy had been their goal, and anarchists their special bête noire. They had fought us and our ideas, not always even by fair means. At last social democracy triumphed in Germany. Popular wrath had frightened the Kaiser out of the country, and the brief revolution had made an end to the house of Hohenzollern. Germany was proclaimed a republic, with the socialists at the political helm. But, oh, the cruel irony of the shades of Marx! Luxemburg and Liebknecht, who had helped to build up the Socialist Party of Germany, were crushed by the régime of their orthodox comrades risen to power.

With Easter came spring's awakening, flooding my cell with warmth and filling it with the perfume of flowers. Life was gaining new meaning --- only six more months to liberty!

April added another political, Mrs. Kate Richards O'Hare, to our company. I had met her once before, when she had called at the prison on her visit to Jefferson City to see Governor Gardner. She had been convicted under the Espionage Law, but she was emphatic that the Supreme Court would reverse the verdict, and that in any event she would not serve time in our place. I had been disagreeably impressed by her dogmatic manner and her belief that exceptions would be made in her behalf, but I wished her luck. When I came upon her dressed in the penitentiary uniform of striped gingham, waiting to fall in line with us as we were marching to the dining-room, I felt sorry indeed that her expectations had miscarried. I wanted to take her by the hand and say something that would ease her first and most trying prison hours, but talking or demonstration of feeling was strictly tabooed. Moreover, Mrs. O'Hare looked rather forbidding. Of tall stature, she carried herself with hauteur, her expression appearing more rigid because of her steel-gray hair. I found it difficult to say something warm even when we reached the yard.

Mrs. O'Hare was a socialist. I had read the little publication she had been issuing together with her husband, and I considered her socialism a colourless brand. Had we met on the outside, we should have probably argued furiously and have remained strangers for the rest of our lives. In prison we soon found common ground and human interest in our daily association, which proved more vital than our theoretical differences. I also discovered a very warm heart beneath Kate's outer coldness and found her a woman of simplicity and tender feeling. We quickly became friends, and my fondness for her increased in proportion as her personality unfolded itself to me.

Soon we politicals --- Kate, Ella, and I --- were nicknamed "the trinity." We spent much time together and became very neighbourly. Kate had the cell on my right, and Ella was next to her. We did not ignore our fellow-prisoners or deny ourselves to them, but intellectually Kate and Ella created a new world for me, and I basked in its interests, its friendship and affection.

Kate O'Hare had been taken away from her four children, the youngest of whom was about eight --- an ordeal that would have taxed the strength of many a woman. Kate, however, was splendid. She knew that her children were well cared for by their father, Frank O'Hare. Besides, in point of intelligence and maturity her children were far above their age. They were their mother's real comrades and not merely the offspring of her womb. Their spirit was Kate's greatest moral support.

Frank O'Hare visited Kate every week and occasionally even more often, keeping her in touch with her friends and their work. He mimeographed her letters and circulated them through the land. The bitter edge of incarceration was thus taken away from Kate. An additional factor to help her over the hardest period was her extraordinary adaptability. She was able to fit into any situation and to go about everything in her quiet, methodical manner. Even the dreadful noises in the shop, and its maddening grind, seemed to have little effect on her. Nevertheless, she suffered a break-down before she had been with us two months. She had over-estimated her strength when she attempted to master the task sooner than any one of us had been able to do it.

But Kate kept her courage and she was greatly sustained by Frank, who had already begun to work for her pardon. She had been convicted for an anti-war speech, but the O'Hares had big political connexions. It was therefore reasonably certain that Kate would not have to serve long. I myself had declined the offer of friends to gain clemency for me. But it was different with Kate, who believed in the political machine. I hoped, however, that in her appeal would also be included the other political prisoners.

Meanwhile Kate was bringing about changes in the Missouri penitentiary which I had in vain been trying for fourteen months to accomplish. She had an advantage in the presence of her husband nearby, in St. Louis, and access to the press, and we often banteringly discussed which of the two was of more value. Her letters to O'Hare, criticizing the lack of a library for the women, and her condemnation of our food, standing for two hours before being served, had appeared in the Post Dispatch and brought immediate improvement. The head matron announced that books could henceforth be had from the men's department, and the food was served hot, "for the first time in the ten years I've been here," as Aggie commented.

In the interim an unusual feature was introduced by the Warden independently of Kate's influence. It was announced that we were to have picnics every second Saturday in the city park. So extraordinary was the innovation that we felt inclined to consider it a joke, too good to be true. But when we were assured that the first outing would actually take place the following Saturday, that we could spend the whole afternoon in the park, where the male band would play dance music, the women lost their heads and forgot all about the prison rules. They laughed and wept, shouted, and acted generally as if they had gone mad. The week was tense with excitement, everyone working to exhaustion to make the task, so as not to be left behind when the great day should arrive. During recreation the sole talk was of the picnic, and in the evenings the cell block was filled with whispered conversation about the impending event --- how to fix up to look nice, how it would feel to walk about in the park. And would the band boys be near enough to talk to? No débutante was ever more wrought up over her first ball than the poor creatures, most of whom had not stepped out of the prison walls for a decade.

The picnic did take place, but to us --- to Kate, Ella, and me --- it was a ghastly experience. There were heavily armed guards behind and in front of us, and not a step was permitted outside the prescribed area. Guards surrounded the prison orchestra, while the matrons let no woman out of sight the moment dancing began. The supper was most depressing. The whole thing was a farce and an insult to human dignity. But to our unfortunate fellow-convicts it was like manna to the Jews in the desert.

In my next letter to Stella I quoted Tennyson's Light Brigade. In the course of the week the Warden sent for me to ask what I had meant by my reference. I told him that I should prefer to remain in my cell Saturday afternoon rather than picnic by the grace of an armed force. There was no danger of any woman's escaping, with the open country-side offering no place to hide. "Don't you see, Mr. Painter," I appealed to him, "it is not the park which will prove an influence for good? It will be your trust in the women, their feeling that at least once in two weeks they are given a chance to eliminate the prison from their consciousness. That sense of freedom and release will create a new morale among the inmates."

The following Saturday there were fewer guards and they did not flaunt their weapons in our faces. Limit restrictions were abolished, and the entire park was ours. The band boys were permitted to meet the girls at the soda-water stand and to treat them to pop and ginger ale. Our suppers in the park were gradually discarded, having proved too hard a task for the two matrons to supervise. But none of us minded it, since we were given another two hours of recreation in the prison yard after supper. The inmates had now something to look forward to and live for. Their state of mind changed; they worked with more zest, and their former distress and irritableness decreased.

One day an unexpected visitor was announced --- S. Yanofsky, the editor of our Yiddish anarchist weekly in New York. He was on a lecture tour to California and he could not pass Jefferson City without seeing me, he said. I was pleased to know that my bitter opponent and censor of yester-year had gone out of his way to pay me a visit. His stand on the war, and particularly his worship of Woodrow Wilson, had completely alienated me from him. It was discouraging that a man of his ability and perspicacity should be carried away by the general psychosis. But, after all, his inconsistency was no worse than that of Peter Kropotkin, who had taken the lead which all the other pro-war anarchists had followed. Yanofsky, however, had gone even further in his enthusiasm for the Allies. He had written a veritable panegyric on Woodrow Wilson and had waxed poetic about "the pride of the Atlantic," that it might carry his hero to European shores for the great feast of peace. Such idolatry of one old gentleman for another outraged not only my principles, but also my conception of good taste.

Our conviction and the shameful manner in which we had been spirited out of New York must have touched something very deep in Yanofsky's heart. He wrote and spoke in our defence, helped to raise funds, and evidenced great concern over our fate. But it was mainly our struggle to rescue Sasha from the San Francisco trap that had established closer rapport between Yanofsky and me. His wholehearted co-operation and his genuine interest in Sasha had shown him capable of devoted comradeship I had never suspected in him before.

My mail had again been held up for ten days. The contents of two letters I had written had been found to be of a treasonable nature. I had ridiculed in them the Congressional committee that was investigating bolshevism in America; I had also attacked the high-handed autocracy of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and his régime, as well as Messrs. Lusk and Overman, the New York State Senators delving into radicalism. Those Rip van Winkles had suddenly awakened to find that some of their countrymen had actually been thinking and reading about social conditions, and that other subversive elements had even dared to write books on the subject. It was a crime to be nipped in the bud if American institutions were to be saved. Of the insidious works those of Goldman and Berkman were the worst, and Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, and Anarchism and Other Essays deserved to be put on the Index Expurgatorius.

My delayed mail brought news from Harry Weinberger about the treatment of Sasha in the Atlanta Federal prison and of our counsel's protest to Washington in connexion with it. Sasha had been confined in an underground dungeon, deprived of all his privileges, including mail and reading-matter, and kept on a reduced diet. The solitary was breaking down his health, and Weinberger had threatened a campaign of publicity against the palpable persecution of his client by the prison administration. Our comrades Morris Becker and Louis Kramer, as well as several other politicals in Atlanta, were sharing a similar fate.

Among my letters was also one containing details of the harrowing death of the brilliant German anarchist Gustav Landauer. Another prominent victim had been added to the number that included Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and Kurt Eisner. Landauer had been arrested in connexion with the revolution in Bavaria. Not satisfied with shooting him, the reactionary fury had resorted to the dagger to finish up its ghastly job.

Gustav Landauer was one of the intellectual spirits of the "Jungen" (the "Young"), the group that had seceded from the German Social Democratic Party in the early nineties. Together with the other rebels he had founded the anarchist weekly, Der Sozialist. Gifted as a poet and writer, the author of a number of books of sociological and literary value, he soon made his publication one of the most vital in Germany.

In 1900 Landauer had drifted from the Kropotkin communist-anarchist attitude to the individualism of Proudhon, which change also involved a new conception of tactics. Instead of direct revolutionary mass action he favoured passive resistance, advocating cultural and co-operative efforts as the only constructive means of fundamental social change. It was sheer irony of fate that Gustav Landauer, turned Tolstoyan, should lose his life in connexion with a revolutionary uprising.

While the Kaiser's socialists were busy annihilating their own political kin, the fate of their country was decided at Versailles. The labour pains of the peace negotiators were long and distressing, the result a still-born child more hideous in a measure than the war. Its fearful effect on the German people and the rest of the world completely vindicated our stand against the slaughter which was to end all slaughter. And Woodrow Wilson, that innocent at the diplomatic gaming-table, how easily he had been duped by the European sharks! The President of the mighty United States had held the world in the palm of his hand. Yet how pathetic was his failure, how complete his collapse! I kept wondering how our worshipful American intelligentsia felt at seeing their idol no longer protected by his Presbyterian mask. The war to end war terminated in a peace that carried a rich promise of more terrible wars.

Among my literary correspondents I greatly enjoyed Frank Harris and Alexander Harvey. Harris had always been very thoughtful, supplying me with his magazine and also frequently writing to me. Owing to his stand on the war, few of his epistles had reached me the previous year, nor any copies of Pearsons', of which Frank was the editor. But in 1919 I was permitted to receive my mail more regularly. I liked Harris's publication more for its brilliant editorials than its social attitude. We were too far apart in our conception of the changes necessary to bring humanity relief. Frank was opposed to the abuse of power; I to the thing itself. His ideal was a benevolent despot ruling with a wise head and generous hand; I argued that "there ain't no such animal" and could not be. We often clashed, yet never in an unkind way. His charm was not in his ideas, but in his literary quality, in his incisive and witty pen and his caustic comments on men and affairs.

Our first clash, however, was not over theories. I had read his The Bomb and had been profoundly moved by its dramatic power. The true historic background was wanting, but as fiction the book was of a high order, and I felt it would help to dispel the ignorant prejudices against my Chicago comrades. I had included the volume among the literature we sold at my lectures, and it had been reviewed by Sasha in Mother Earth and advertised in our columns.

We had been roundly condemned for it by Mrs. Lucy Parsons, the widow of Albert Parsons. She denounced The Bomb because Harris had not kept to the actual facts, and also because Albert emerged from the pages of the book a rather colourless person. Frank Harris claimed to have written, not a history, but a novel of a dramatic event. I had no quarrel with him on that score. But Mrs. Parsons was entirely right in repudiating Harris's erroneous conception of Albert Parsons.

I had expressed my surprise to Frank at his apparent failure to appreciate the personality of Parsons. Far from being colourless or weak, he should have been, together with Louis Lingg, the hero of the drama. Parsons had deliberately walked into the arena to share the fate of his comrades. He had done more; he scorned a chance to save his own life by accepting a pardon because it did not include the lives of the other men.

In reply Frank explained that he had made Lingg the outstanding personality in his novel because he had been impressed by the determination, fearlessness, and stoicism of the boy. He had admired Lingg's contempt for his enemies, and his proud choice of death by his own hand. Since he could not have two heroes in one story, he had given preference to Lingg. In my next letter I called his attention to the fact that the best Russian writers, such as Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, often had more than one hero in their works. Moreover, the sharp contrast between Parsons and Lingg would have only enhanced the dramatic interest of The Bomb had the true grandeur of Albert Parsons been faithfully portrayed. Harris admitted that the values of the Haymarket tragedy had by no means been exhausted in his book; perhaps some day he would write a story from another angle, with Albert Parsons as the dominant figure.

Alexander Harvey's correspondence greatly amused me. He worshipped at the shrine of Greek and Latin culture; nothing that had come to us since counted for much in his estimation. "Believe me," one of his letters read, "the truest conscientious objector was Sophocles. The decay of the ancients goes hand in hand with the loss of liberty. You yourself remind me of Antigone. There is something splendid and Greek in your life and in your gospel." I wanted him to explain the existence of slavery in his beloved old world, and I asked for enlightenment on how it happened that I, who had never looked at a Latin or Greek grammar, should yet prize liberty above everything else. His only explanation was several volumes of Greek plays in English translation.

My library had been greatly enlarged by many books friends had sent me, among them works by Edward Carpenter, Sigmund Freud, Bertrand RusseII, Blasco Ibañez, Barbusse, and Latzko, and Ten Days that Shook the World. John Reed's story, engrossingly thrilling, helped me to forget my surroundings. I ceased to be a captive in the Missouri penitentiary and I felt myself transferred to Russia, caught by her fierce storm, swept along by its momentum, and identified with the forces that had brought about the miraculous change. Reed's narrative was unlike anything else I had read about the October Revolution --- ten glorious days, indeed, a social earthquake whose tremors were shaking the entire world.

While still in the atmosphere of Russia, I received --- significant coincidence! --- a basketful of deep-red roses, ordered by Bill Shatoff, of Petrograd. Bill, our co-worker in many fights in America, our jovial comrade and friend, in the very midst of the Revolution, surrounded by enemies within and without, facing danger and death, thinking of flowers for me!

Go to Chapter 49

Return to Table of Contents

|